EARLY HISTORY OF DRAKELOW

Drakelow is first recorded as Dracan Hlawe in a grant of land made by King Edward in 942 A.D. The place-name means “Dragon’s Mound”, indicating a burial place with a guardian spirit.

No trace of an early burial was found until January, 1962, when workmen with a mechanical digger were excavating gravel to make concrete for the construction of ‘C’ power station.

The site was in an orchard adjoining the former Warren Farmhouse and the “find” consisted of a small jar or bowl, globular in shape, with a base diameter of one and a half inches, and a height of two and a half inches. Made of well-fired grey-brown ware, it had a stamped decoration of horse shoes around the neck with incised chevrons and square stamps enclosing a cross on the body.

The site was in an orchard adjoining the former Warren Farmhouse and the “find” consisted of a small jar or bowl, globular in shape, with a base diameter of one and a half inches, and a height of two and a half inches. Made of well-fired grey-brown ware, it had a stamped decoration of horse shoes around the neck with incised chevrons and square stamps enclosing a cross on the body.

This small pot is a good example of a vessel containing a votive offering and is usually associated with a skeleton, but of the latter there was no trace.

The date of this vessel has been fixed at c550 A.D. and it is an interesting example of Friesian-Anglo-Saxon design. It is now in Derby Museum.

In the reign of Edward the Confessor, Drake-low was held by an Anglo-Saxon named Elric.

THE NORMAN CONQUEST AND AFTER

When this country was invaded by William the Conqueror in 1066 he was accompanied by the brothers Ralph and Robert de Toeni, who claimed descent from the Dukes of Normandy, with a pedigree extending back to Norse mythology.

Ralph, the elder, was hereditary Grand Standard Bearer to the Duke, but asked to be relieved of this duty so that he might fight in the battle of Hastings. He was rewarded with several manors in Norfolk and elsewhere, but spent most of his time on his ancestral estates in Normandy, Robert was given 81 manors in Staffordshire, 26 in Warwickshire, 20 in Lincolnshire and four elsewhere, and he adopted the surname of “de Stafford”.

Nigel, a younger brother or possibly a son of Robert, also assumed the surname of “de Stafford”, and held 13 manors in Staffordshire, 11 in Derbyshire, four in Leicestershire and one in Warwickshire. Among the Derbyshire manors held by Nigel at the time of the Domesday Survey in 1086 were those of Drakelow, Heathcote and Swadlincote, together with a pasturable wood two and a half miles long and two miles wide. There is no mention of Gresley in the Domesday Book.

Somewhere about the year 1090, Drakelow was stricken with pestilence and an account of this happening was written by Geoffrey, Abbot of Burton (1114-1151). Two of the Abbey servants living at Stapenhill fled to Drakelow desiring to live under the protection of Roger, Earl of Poictou, at that time holder of the great fief of Lancaster which included the manor of Drakelow.

The Abbey officials seized the seed corn of the servants, hoping this would induce them to return, but the Drakelow retainers came to Stapenhill and carried away all the seed corn in the Abbey barns. The Abbot refused to use armed force but went on naked feet to the shrine of St. Modwen in the Abbey Church to pray for guidance. It is recorded, however, that ten of the Abbot’s retainers met 60 Drakelow retainers at the “black pool by the Trent” and a fight took place (as this account was written by the Abbot it is possible the contestants were more equal in numbers).

The steward of Drakelow was killed and the offending servants were stricken with a mortal sickness. After their burial, horror upon horror fell upon the quiet village of Drakelow. Night after night the dead servants rose from their graves and rushed about the fields carrying their coffins on their shoulders and banging them on the walls of houses. Finally all the villagers were stricken with sickness. The Earl made repentance to the Abbot but the ghosts were not laid until the bodies of the offending servants had been dug up and burned “when an evil spirit in the form of a large black crow flew up out of the smoke and disappeared from view. Thereafter the village of Drakelow was forsaken and desolate, the surviving inhabitants fleeing to the nearest village which is called Gresley”.

William de Gresley’s grandson, also named William, returned from Gresley to Drakelow at the beginning of the 13th century. In a deed dated 1201 he is mentioned as holding Drakelow from King John by service of a bow, a quiver, and twelve arrows yearly, the bow to be unstrung, the quiver of Tutbury make, and the arms feathered, with the addition of a bozo or broad-headed shaft.

William died in 1220 and was succeeded by his son, Geoffrey, who became steward to the powerful William de Ferrers, 4th Earl of Derby and Constable of the High Peak. The Gresley arms which appear for the first time on Geoffrey’s seal are an adaptation of the Ferrers coat of arms.

Geoffrey’s grandson, also named Geoffrey, supported Simon de Montfort against Henry III and had to pay a large sum to redeem his forfeited estates. This Geoffrey de Gresley appears to have been of a turbulent disposition for he was accused several times of rioting and was fined for wounding Ralph le Messer at Lullington. He subsequently fought in France and Scotland and was knighted by Edward I and summoned to Parliament. He successfully claimed the right to erect a gallows at Drakelow for the execution of felons.

Sir Geoffrey had three sons, Peter, Robert and William, all of whom inherited the turbulent qualities of their father. Robert and William were outlawed for murder in 1293 and Peter, the eldest son, followed the example of his father by joining the army after many misdeameanours. He was knighted in 1307 and died in 1310.

Sir Peter’s wife, Joanna de Stafford, by whom he had six sons, was also not averse to violence. After her husband’s death she was forcibly adbucted from Drakelow and married to Sir Walter de Montgomery. The abductor was pardoned but in 1323 Joanna and her sons, Robert and Peter de Gresley, were accused of the murder of William de Montgomery, Sir Walter’s son by an earlier marriage.

The murder took place on “the high road in Overseale”, the fatal wound being inflicted by a “sword of Cologne worth 6/10.” All three persons accused were arrested – and acquitted.

In 1333 Joanna was accused of another murder and acquitted. Her eldest son, Peter, after robbing the parson of Walton and attempting to murder John Green, was slain a few years later. His brother Robert was accused of ten crimes including three of robbery and four of murder but he joined the King’s army in Scotland and fought so well that he was granted a free pardon for all his crimes, was knighted, and represented Derbyshire in Parliament.

In a deed executed by Peter’s grandson, John de Gresley, in 1394, it is stated: “Be it know that I, John de Gresley, have not had the use of my seal for a whole year. I therefore notify that, being of good memory and sound mind, I contradict and deny in all things any sealed writings until my seal is restored, and I have set to this deed the seal of Dean of Repton”.

Sir John had married as his second wife a wealthy heiresss, Joan de Wastneys, but they had no children. Nicholas, the son of his first marriage, died in 1390 and it appears that Sir John’s grandson, Thomas, was afraid the Wastney’s inheritance might go astray. A complaint was made by Joan to the Lord Chancellor that, while she and her husband were in possession of Drakelow, Thomas Gresley came there with 24 armed men and ransacked the chambers and chapel, breaking open 25 chests and carrying away £264 in gold as well as silver seal of arms belonging to Sir John and a quantity of linen and woollen clothes, furs and skins, worth £ 100, together with four score charters and muniments.

She went on to say that Sir John, in great infirmity (he was 80 years of age), was detained by Thomas and his people by main force so that she could not, and dare not go to his aid. The cause of the trouble was that Sir John had made her his executrix in place of Thomas, and with the family seal in his possession he might do as he liked. But Thomas eventually succeeded to all his grandfather’s property including the Wastney’s inheritance.

Nigel de Stafford, who retained that name all his life, had two sons, William and Nicholas. The latter married an heiress of the Longford family and went to reside there, but William, the elder son, remained at Gresley. His name first appears in a deed in 1129 and he died in 1166. In various deeds and charters he described himself as William, son of Nigel of Gresley, and this became the family name.

Somewhere about 1130, William de Gresley built a small priory dedicated to St. George for the use of canons of the Order of St. Augustine. Known as the “Black Canons” from their dress, these monks grew beards and wore little caps or birettas. They carried out the duties of parish priests but lived together on monastic lines.

The site of this priory was on another hill in the same large wood as the “motte and bailey” castle, and in the course of time the two settlements became known as Castle Gresley and Church Gresley. The present parish church of Gresley is on the site of the old monastic church, on the south side of which were the priory buildings.

That the Priory of Gresley was a small foundation is borne out by a grant which was confirmed by the Bishop of Lichfield in 1309 which states: “Although the Prior and Cannons of Gresley are bound to perform divine worship by day as well as by nights, and are compelled to exercise the burden of hospitality, yet from the fewness of the brethren which consist of only four in number, together with the Prior, and from the main estate of the house and the barrenness of its lands, and divers oppressions which daily gain strength as the malice of the world increases, they are unable to bear as is fitting the yoke of the Lord. So to augment the number of brethren we bestow upon them the parish church of Lullington, so that the aforesaid monks may increase their numbers by two canons”.

The Assize Rolls of Edward III contain an account of an unusual fatality which occurred in the Priory. “In the 14th year of the reign of the King’s father one William de Jorganville was sitting by the fire in the kitchen of the Prior of Gresley when suddenly his clothes caught fire and he was burned so badly that the third day afterwards he died. No one is suspected of his death. Verdict: Misadventure”.

THE WARS OF THE ROSES AND THE GRESLEY FAMILY

In the difficult times of the Wars of the Roses many wealthy landowners were ruined but the Gresleys contrived to keep their estates intact. Sir Thomas Gresley, a staunch Lancastrian, was knighted by Henry IV and at different times was Sheriff of Derbyshire and Staffordshire. He represented one or other of these counties in Parliament on no less than seven occasions.

Both Sir Thomas and his son John took part in the French expeditions of Henry V, Sir Thomas furnishing three men-at-arms and nine archers, while John contributed two men-at-arms and six archers. Among the family papers was an interesting indenture between Sir Thomas and John Bette, a yeoman of Rosliston, whereby the latter agreed to serve, follow and guard Sir Thomas in France for a wage of 6d. per day, and to be well mounted for service in the war.

On the death of Henry V, Jane Gresley, daughter of Sir Thomas, was appointed nurse to the infant Henry VI, then a few months old. On relinquishing her duties she was awarded a pension of £40 p.a. (equivalent to more than £2,000 p.a. today) and her successor, Dame Alice Botiller, was given permission by the Privy Council “reasonably to chastise the child from time to time as the case may require“. To have struck the King without such permission would have been a treasonable offence!

Sir John Gresley, a grandson of Sir Thomas, appears to have trimmed his sails to the prevailing wind. At one time a Lancastrian he afterwards supported Edward IV and accompanied him to Scotland. He attended the coronation of Richard III and subsequently accompanied Henry VII in his triumphal progress to the north.

Sir John had several disputes with the Abbot of Burton about fishing rights in the river Trent, and quarrelled violently with Sir William Vernon who owned land at Seale. This resulted in a fracas and the disputants were bound over to be of good behaviour, the following terms of compensation being fixed:

“For a sore wound on head or face 13/4d., an ordinary stroke 6/8d., a sore stroke on the leg if the bone was stricken asunder 40/-, a stroke on the foot 20/-, but if it results in maiming the compensation is to be 100/-, the latter amount also to be paid in respect of maiming hand or thumb”.

Sir John became Sheriff of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire and represented Staffordshire in Parliament.

John’s grandson William, married a granddaughter of Sir William Vernon, thus uniting the disputing families, but they had no children. Sir William Gresley, however, had four sons by a lady named Alice Tawke, all of whom assumed the surname of Gresley. She afterwards married Sir John Savage and on Sir William’s death in 1521 she disputed the succession of Sir George Gresley (William’s brother) to the family estates.

The dispute was referred to Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York, who decreed that Sir George should have possession of the family manors “as the rightful heir of his brother Sir William Gresley who died without lawful issue of his body begotten“. The documents were endorsed. “The decree against Lady Savage and her bastard sons for all the Gresley Lands“.

During the troublesome times of the Reformation the Gresleys managed to avoid persecution and forfeiture of their lands. Sir George was knighted by Henry VIII at the coronation of Anne Boleyn, and his son William was knighted by Queen Mary Tudor on the occasion of her accession, while William’s son, Thomas Gresley, was appointed Sheriff of Staffordshire by Elizabeth I and knighted by James I.

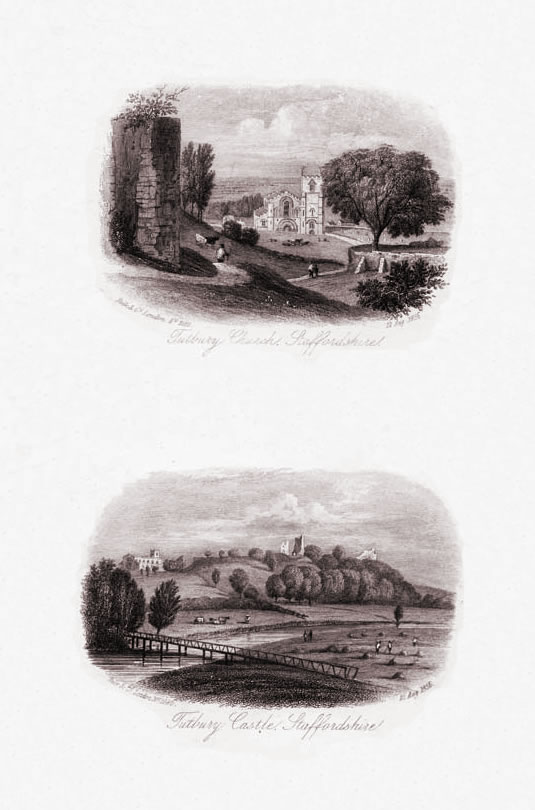

Thomas Gresley was appointed Sheriff for Staffordshire in 1583. This was an eventful year, for Mary Queen of Scots was moved from Sheffield to Wingfield and thence to Tutbury. The latter place was cold and damp, and Thomas Gresley, as Sheriff, was ordered to take an inventory of the goods belonging to Lord Paget at his house in Burton. Lord Paget, a Roman Catholic, and a suspected supporter of the Scottish queen, had fled to France. On receipt of the inventory the Sheriff was ordered to take some valuable hangings from the walls of Lord Paget’s house to render Tutbury Castle more comfortable.

It appears, however, that Thomas Gresley had sold some of the hangings and also some beds, and when Queen Mary complained of the cold at Tutbury he received an emphatic order that these hangings should be recovered and sent to Tutbury. Matters were adjusted, not without difficulty, and when the Scottish queen was removed to Fotheringhay, Thomas Gresley, as Sheriff, was ordered to attend her. The fact that he was present at her execution, however, did not impair his relations with her son, James I, who rewarded him with a knighthood on the occasion of his progress from Scotland toLondon.

Thomas Gresley took an active part in county affairs and was one of the signatories to a protest against a forced loan levied by Queen Elizabeth in 1590. Six year later two suspected Stapenhill witches were brought before him in his capacity as Justice of the Peace. A boy named Thomas Darby was suddenly attacked by fits and was supposed to have been bewitched either by Alice Gooderidge or her mother, Elizabeth Wright. The two unfortunate women were arrested and taken to Drakelow where they were searched for “witch-marks”, i.e. any blemish on face or body. These were found and a witness named Michael testified that when his cow was sick Elizabeth Wright cured it on payment of a penny fee.

Alice Gooderidge confessed she had bewitched the boy and was sent to Derby gaol. She was tried and condemned to death but died in prison before the date fixed for her execution. Three years later the boy confessed that his fits were frauds and he had never really been ill, adding “I did it to get myself a glory thereby“.

DRAKELOW IN THE 17th & 18th CENTURIES

Sir Thomas was succeeded by his son, George, who continued in high favour with James I and was included in the first list of baronets created by that monarch in 1611. Each applicant for this hereditary title had to provide thirty foot soldiers at 8ds. per day for three years for the settling of Ulster, or compound for this by a single payment of £1,095. The original number of baronets was 200, and they ranked above all knights except Knights of the Garter.

Sir George spent most of his time at Drakelow but was a member of the short-lived Parliament of 1628-9. Possibly this brief session shook his confidence in Charles I, for when the struggle between King and Parliament began in 1642, he took up arms on the latter side. This was a brave thing to do for Sir George was the only ‘gentleman of quality’ in South Derbyshire to join the Parliamentary forces at Derby where he commanded a troop of horse under Colonel Gell.

There were Royalist strongholds at Tutbury, Lichfield and Ashby de la Zouch which plundered and laid waste his estates including Drakelow, so that in 1644 Sir George had to apply to Parliament for financial assistance and was voted £4 per week. Although the Parliamentary forces were eventually victorious, Sir George suffered heavy losses and was the first of his line to sell some of his estates including the manors of Colton, Rosliston and Seale.

The following extract is from a MSS of Sir George Gresley formerly preserved at Drakelow. It is entitled “A true account of the raising and employing one foot regiment under Sir John Gell”.

“Now let any indifferent and impartial man judge whether our single regiment of foot hath been idle…..Prince Rupert with his army came once against us, the Earl of Newcastle in person twice, and the Queen when she lay as Ashby earnestly pressed the plunder of this town (Derby) as a reward to her soldiers, and yet we are safe.

Let wise men consider if this town had been lost and malignant lords and gentlemen in possession of this place what would have become of our neighbour Counties?

That the world may know we neither undertook this business with other men’s money nor have since employed any man’s estate to our profit. We had no advance money either from Parliament or our Country, or from any other man or woman, but went upon our own charges. Our Colonel hath since sold his stock, spent his revenue, and put himself into debt in maintenance of this cause. We are out of pocket many hundreds of pounds spent only on this business, not that we are weary of the cause but are absolutely resolved to continue and persevere so long as God shall give us lives to venture and estates to spend“.

One effect of the dissolution of the monasteries was to throw the burden of poor relief upon churchwardens and overseers of the poor and it was ordered that a general assessment for the relief of the poor should be made in every township.

In 1682 an appeal to the Quarter Sessions was made by the inhabitants of Church Gresley, Castle Gresley, Swadlincote, Oakthorpe and Donisthorpe, and parts of the parish of Gresley, that they were not able to raise enough money for the relief of the poor in their hamlets, but Sir Thomas Gresley and the inhabitants of the hamlet of Drakelow, having no poor, had claimed exemption from the rate and had paid nothing toward it. The Court ordered that Sir Thomas and the inhabitants of Drakelow should show cause why they should not be assessed to tax.

At the following Sessions it was ordered that as the manor of Drakelow of the yearly value of £400 is not charged with any poor, Sir Thomas Gresley will pay a third part of the levy, in other words, if the levy be fixed for £24, Sir Thomas shall pay £8, and the same rate for a greater or lesser amount to be paid to the overseers and churchwardens for the relief of the lame, impotent, old, blind, and such others being poor and unable to work.

Sir Thomas Gresley, the second baronet, had 14 children, two of whom made unusual marriages. Dorothy, the fourth daughter eloped with one of her father’s servants at 1 a.m. on June 18th, 1681, and was married by licence at Tutbury Church eight hours later. She was never forgiven by her mother.

The eldest son, William, at the age of 35, decided it was time he took a wife. So he journeyed into Shropshire and proposed to an heiress who refused him. Having made up his mind not to return without a wife he proposed to her eldest sister who accepted him. But the news did not please his parents when they learned that she was a widow with seven children.

However, ‘Squire Bill’, as he was known, declared he would have her “and that quickly too, for hunting is coming and then no time!” He also threatened to shoot his mother if she did not agree and she fled to Burton. But a reconciliation took place when his family learned that the widow had an income of £250 p.a. and invested funds worth £2,000, the children of her first marriage being otherwise provided for. Squire Bill, a man of few words, afterwards declared her “best wife in world”, and she presented him with three more children.

Sir Nigel, sixth baronet, grandson of Squire Bill, succeeded unexpectedly to the title and family estates when his elder brother died from smallpox at the age of 30. Nigel was a Captain in the Royal Navy and it was in his ship that Flora Macdonald, who aided the escape of “Bonnie Prince Charlie”, was conveyed to London after the abortive rebellion of 1745. As a reward for his kindness and courtesy, she presented him with her portrait which was hung in Drakelow Hall. An inscription on the back stated:

“This portrait of Flora Macdonald was given by herself to Sir Nigel Gresley, Captain in the Royal Navy, who captured her in flight from Scotland to France and from whom she experienced every courtesy and as a mark of her gratitude presented him with this picture in 1747”.

Sir Nigel inherited extensive property in Staffordshire from his mother, a daughter of Sir William Bowyer, and became a patron of James Brindley, the engineer. With his aid the “Gresley Canal” was built, nine miles in length, to convey coal and ironstone from mines at Apedale to the Grand Trunk Canal at Newcastle-under-Lyme, on condition that coal should be supplied to the inhabitants of the latter place at 5 shillings per ton.

Sir Nigel was a good-natured man of great size and an old inhabitant of Netherseale described him as the biggest man he ever saw in his life “except for a giant in a show”. When he worshipped in Netherseale Church it is said he had to wriggle sideways into the Hall pew!

Like his father, Sir Nigel Bowyer Gresley, the seventh baronet was interested in the improvement of his estates, and he endeavoured to improve the quality of local pottery.

At that time the pottery produced in Gresley and Swadlincote was a coarse brown earthenware made from a bluish-white superfine clay. In 1795, Sir Nigel, in collaboration with a relative. Mr. C.B. Adderley of Hams Hall, established a porcelain factory in buildings erected about fifty yards from Gresley Hall. The services of William Coffee, a modeller from the Derby China factory, were secured, and Sir Nigel’s daughters are said to have painted some of the patterns. But most of the pottery cracked in firing and the experiment proved a failure.

An order for a magnificent dinner service was obtained from Queen Charlotte through her Chamberlain, Col. Disbrowe, of Walton Hall, but it was never completed as the china came out of the ovens cracked and crazed. So far as the writer is aware Gresley china bore no distinctive markings. Specimens were preserved at Drakelow Hall and others can be seen in Museums at Derby and Birmingham. In the possession of Lord Gretton at Staple ford Hall, is a dessert service comprising 34 pieces with flower springs in colour on a yellow and gold background.

THE GRESLEYS OF NETHERSEALE

The Manor of Seale was purchased from Sir George Gresley by Gilbert Morewood, a London merchant and friend of Sir John Moore, who built a school at Appleby in Leicestershire. Seale derives its name from ‘Scegel’ which meant ‘a small wood’. This wood divided the manor into two parts – upper and lower, now known as Overseal and Netherseal.

This manor was soon restored to the family by the marriage of Gilbert Morewood’s daughter to Sir Thomas Gresley, the second baronet, and in due course it was settled upon the second son of the marriage. By this means a branch of the Gresley family became established at Netherseale and when the main line of the family died out in 1837 with the death of the 8th baronet, a descendant of this branch succeeded to the title and the family estates.

Frances Morewood, Lady Gresley, appears to have been a forceful character. In a letter to Sir John Moore concerning Mr. Waite, a schoolmaster who lived within a mile of Drakelow and had been recommended for the head mastership of Appleby School, she remarked that Sir John was right not to appoint any one to that position for life but only while of good behaviour, adding that Repton School had been ruined by the opposite principle. In their old age Frances and her husband acquired the reputation of being miserly and a tradition arose that large sums of gold and silver were hidden in Drakelow Hall – but none was discovered when the mansion was demolished in 1926.

SIR ROGER AND THE LATER GRESLEYS

Sir Roger Gresley, eighth baronet, succeeded to the title when eight years old. He grew up to be a man of many parts, a politician, a dandy, an author, a virtuoso, a sportsman, a country gentleman, and an antiquary. He became High Sheriff of Derbyshire and a Captain in the Staffordshire Yeomanry. Sir Roger fought several Parliamentary elections and incurred considerable debts thereby. In 1828 he sold the site of the Priory at Gresley, as well as the Castle Knob and Gresley Hall. In 1836 he sustained severe injuries by a fall from his horse and died from the effects a year later.

Sir Roger, against his mother’s wishes, married Sophia, youngest daughter of the Earl of Coventry, and their only child leved only a few weeks. So, on Roger’s death, the title and family estates passed to his cousin, the Rev. William Nigel Gresley, Reactor of Seale, with the exception of a life interest in Drakelow which passed to Roger’s widow.

Lady Sophia married as her second husband Sir Hentry des Voeux Bt., who lived with her at Drakelow Hall, and as she did not die until 1875, the ninth and tenth baronets never resided there.

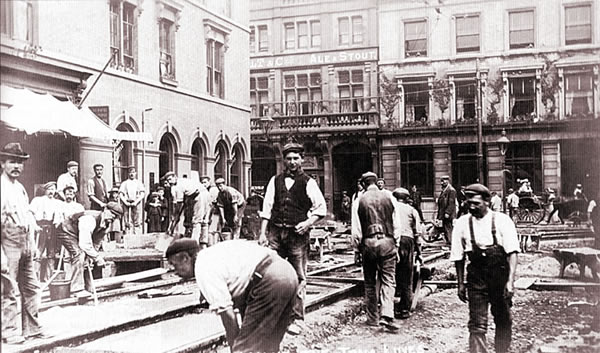

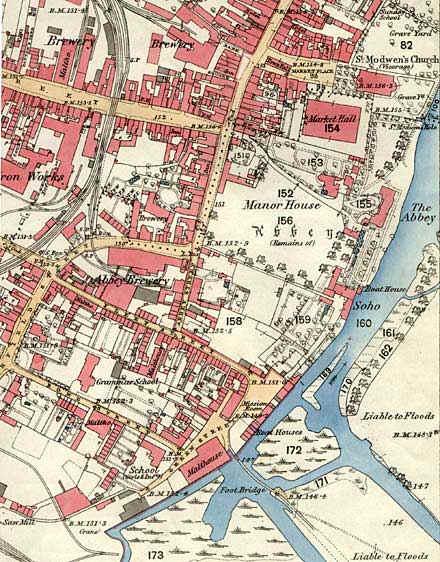

Concerning Sir Henry des Voeux while living at Drakelow, there are two good stories told. When Swadlincote market hall was built by public subscription in 1861, the money was insufficient to install a clock and the Vicar, the Rev. J.R. Stevens, undertook to ask Sir Henry for a donation. Unfortunately, Sir Henry, suffering from gout, had just received news of the loss of a lawsuit, so the Vicar’s request met with a curt refusal. On second thoughts however, Sir Henry added: “You can have your clock if these words are placed beneath it, ‘TIME THE AVENGER’. I’ll beat these lawyers yet”.

The other story was related to me by the late Charles Hanson, a noted local sportsman (1836-1931). Sir Henry gave him permission to shoot wildfowl on the Trent at Drakelow provided certain ducks were left alone. But when one of these birds suddenly rose before him he brought it down with a quick shot. Unluckily Sir Hentry saw this happen and summoned him to the Hall. On arrival the butler warned him Sir Henry was very angry. As he entered the room he was greeted by the words “What the devil do you mean by shooting that duck, you will not shoot here again”. After this wigging he was dismissed and met the butler on his way out. “What did the old man say?” he queried. “Oh it’s all right”, was the reply “he told me to ask you for a drink!”

Some time late Sir Henry said to the butler “Has that young devil gone?” “Yes, Sir Henry”, was the reply, “and I gave him a drink as instructed”. This amused Sir Henry so much that he sat down and penned a letter restoring permission to shoot on the estate again.

The Rev. Sir William Nigel Gresley, who succeeded his cousin Roger as ninth baronet, had followed his father as Rector of Netherseal in 1830 and spent the remainder of his life there. To pay Sir Roger’s debts the manor of Lullington was sold to C.R. Colville for £98,000.

Devoted to hunting, Sir William was forced to give this up owing to ill health and on his death in 1847 he was succeeded by his son Thomas as tenth baronet, who was at that time a Captain in the 1st Dragoon Guards and an aide-de-camp to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

More of the Gresley inheritance was sold by him, including Coton Park and land at Church Gresley and Linton. He was elected to represent South Derbyshire in Parliament in November, 1868, but died a month later. As Drakelow was still occupied by Lady Sophia, he resided at Caldwell Hall, lent to him by Sir Henry des Voeux Sir Thomas was succeeded as eleventh baronet by his son, Robert, who was then only two years old.

On the death of Lady Sophia des Voeux in 1885 the Drakelow estate came into the possession the new baronet. As he was still a minor, Drake-low Hall was let for a time to John Gretton, the brewer, who came there with his family from Bladen House, near Burton-on-Trent. The family included John Gretton junior (afterwards the 1st Baron Gretton of Stapleford Park) and his brothers Frederick and Rupert and his sister Katherin.

On attaining his majority Sir Robert Gresley took up residence at Drakelow and in 1893 he married the eldest daughter of the eight Duke of Marlborough. A Deputy Lieutenant for Derbyshire and later High Sheriff, he took an active part in county affairs.

Sir Robert made many improvements in the mansion and gardens at Drakelow and was. responsible for the construction of the terraced river frontage of the hall. He was one of the best shots in England and reared game on a large scale, but increasing taxation and dwindling resources finally compelled him to sell the estate of his ancestors of which he was so proud.

He died in 1936 and was succeeded by his eldest son Nigel (born 1894) as the twelfth baronet. The heir to the baronetcy is Sir Nigel’s brother Laurence(born 1896).

A notable member of the family was the Rev. John Morewood Gresley, the son of the Rev. William Gresley and half brother of the ninth baronet. Educated at Appleby Grammar School and Harrow, he graduated M.A. at Oxford and took Holy Orders, becoming Reactor of Seale and subsequently Master of Etwall Hospital. A Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and an archeologist of some renown, he married a great granddaughter of Dr. William Stukeley, the celebrated antiquary.

The Rev. J.M. Gresley was a founder of the Leicester Archaeological Society and of the Anastatic Drawing Society. In 1861 he carried out an extensive and systematic excavation of the foundations of Gresley Priory. He also compiled “Stemmata Gresleyana” and gathered together a large number of family papers which were extensively used in the compilation of ‘The Gresleys of Drakelowe’ by F.C. Madan in 1899.

During the course of a Parliamentary election at Ashby de la Zouch in 1865 he imprudently drove into the town with his horses and carriage decorated with blue ribbons. These Conservative colours infuriated some people so much they surrounded his carriage and followed him into a house in Wood Street where he was handled so roughly that he died a few months later.

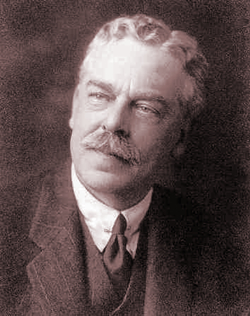

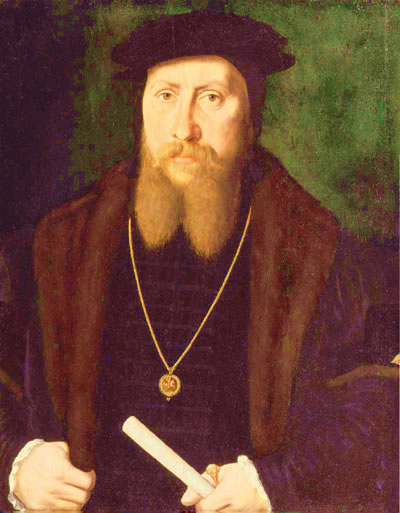

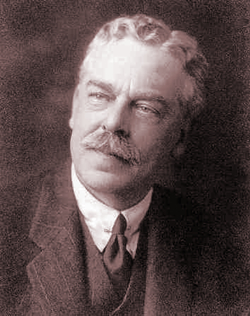

Another notable member of the family was Sir Herbert Nigel Gresley, C.B.E., D.SC, M.I.C.E., M.I.MECH.E., M.I.E.E. shown here. He was born in 1876 he was the fourth son of the Rev. Nigel Gresley (9th baronet) and nephew of Sir Thomas Gresley (10th baronet) and cousin of Sir Robert Gresley (11th baronet).

Another notable member of the family was Sir Herbert Nigel Gresley, C.B.E., D.SC, M.I.C.E., M.I.MECH.E., M.I.E.E. shown here. He was born in 1876 he was the fourth son of the Rev. Nigel Gresley (9th baronet) and nephew of Sir Thomas Gresley (10th baronet) and cousin of Sir Robert Gresley (11th baronet).

Sir Nigel, as he preferred to be called, was educated at Marlborough and early evinced an interest in railway locomotives, sketching them at the age of 13. After serving as an apprentice in the railway works at Crewe, he entered the service of the L. & Y. Railway at Horwick, and in 1905, at the age of 31, was appointed carriage and wagon superintendent of the G.N. Railway at Doncaster.

Sir Herbert Nigel Gresley first worked on the railways as an apprentice at Crewe eventually working for the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. Appointed carriage and wagon superintendent of the Great Northern Railway in 1905. In 1911 he was appointed locomotive engineer, being then in his thirty-sixth year and in the same year, he succeeded H.A. Ivatt as Chief Mechanical Engineer. In 1923 he was appointed Chief Mechanical Engineer of the London & North Eastern Railway, being knighted in 1936. He was also president of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers in 1936.

During the First World War of 1914-18 war, he was responsible for the design of armoured trains and held the rank of Lt. Colonel in the Royal Engineers. On the grouping of the railways he became chief mechanical engineer of the L.N.E. Railway and had the task of integrating the technical staffs of the constituent companies into one team. For over 30 years he exercised an influence over the design of British locomotives in a career which has no parallel.

He designed the silver jubilee trains of 1935 and on November 26th, 1937, the name-plate “Sir Nigel Gresley”, affixed to his 100th “Pacific” locomotive, was unveiled by the chairman of the L.N.E. Railway – a tribute never before paid to any living locomotive engineer. This picture shows the 100th Pacific locomotive, which was named after him.

Sir Nigel was created C.B.E. in 1920 and knighted in 1936. He died in 1941, three months before he was due to retire, and is buried in Netherseal church near the home of his ancestors.

THE GRESLEY COAT OF ARMS

The Gresley Arms are “Vaire, ermine and gules” (i.e. silver and red). Armorial bearings came into use during the last quarter of the 12th century and it was not unusual for a tenant at that time to adopt the arms of his feudal lord.

It is therefore probable that William de Gresley, who was exempted from all but nominal service to his feudal overlord, William Ferrers, 4th Earl of Derby, in 1200, assumed the Ferrers Coat of Arms “Vaire or and gules” (i.e. gold and red) with a change of tincture.

These arms appear for the first time on the family seal of Geoffrey de Gresley circa 1240. With the creation of the baronetcy in 1611, the badge of Ulster was added to the cost of arms borne by the head of the family.

The family crest is a “lion passant, ermine, armed, langed and collared gules” the first occurs in 1513.

The family motto is meliore guam fortuna – “More faithful than fortunate” – but this appears to have been an invention of the 18th century.

DRAKELOW HALL, GRESLEY HALL AND GRESLEY CHURCH

The site of the earliest mansion or castle at Drakelow is unknown, but there is evidence of an early structure at the junction of the Walton and Rosliston roads. The site of the moat is clearly visible and it enclosed an area measuring 75 yards by 75 yards. This site was outside Drakelow Park, which was enclosed at a much later date. Excavation would probably reveal traces of foundations of a structure which may have been built by William de Gresley on his return from Castle Gresley in 1201.

It was notable that this piece of land was excluded from the sale of the Barn Farm, of which it forms part, in 1933. At the final sale of the remainder of the Drakelow Estate it was purchased by Mr. J. Hulse, of the Barn Farm, who felled the trees growing on it and eventually sold the land to Sir Clifford Gothard the present owner of the farm.

At present the land is covered with a thick growth of scrub but it is hoped that at some future date a systematic excavation of the site may yet take place to throw some light upon its past history.

It would appear that between 1086 and 1090 a motte and bailey castle of the usual Norman type had been built in a clearing in the large wood mentioned in the Domesday Survey, and that Nigel de Stafford was in residence there. Of 51 of these Norman structures, 36 were built in places insignificant before the Norman Conquest. These strongholds were erected to overawe the Anglo-Saxons, and to serve as a place of refuge in case of any uprisings.

A wide ditch of considerable depth was dug in a circle, the earth being thrown inwards to form a lofty mound, advantage being taken of a natural mound if this was available. On the flattened top of the mound, or ‘motte’, a wooden tower was erected to serve as a residence for the lord and his family.

In addition to the ditch, which was crossed by a drawbridge, the mound was protected by a wooden stockade. Outside the ditch a “baily” or courtyard, of varying extent but usually of half-moon shape, was surrounded by a further ditch and also protected by a stockade. Within this space, huts, barns and cattle shelters were erected for labourers attached to the manor. As the structure and palisades were of wood there are no visible remains except the mound which is now known as ‘Castle Knob’. It is from this ‘motte and bailey’ castle erected in a ‘Grassy Lea’ in the large wood that the place-name of GRESLEY is derived.

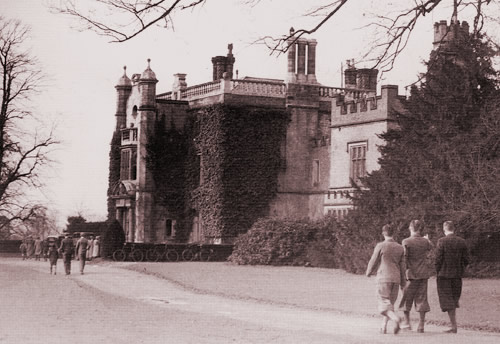

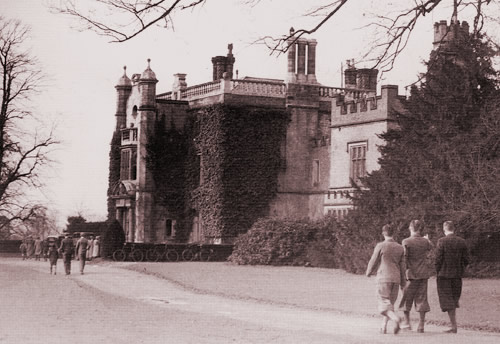

Concerning the late hall in Drakelow Park, Sir Robert Gresley (eleventh baronet) stated that the date of foundation of this structure was not known, nor was it easy to determine from the available evidence. Described in the sale catalogue as ‘Elizabethan’, it may have contained some earlier work, but during successive centuries considerable alterations and improvements had been effected.

The greater part of the mansion was apparently rebuilt by Sir William Gresley (fourth baronet) in 1723 for this date appeared on several leaden waste-pipe heads.

Sir Roger Gresley (eighth baronet) altered the west front considerably and built a billiard room and the bedrooms above it c1830. Sir Robert (eleventh baronet) also effected some alterations and improvements both in the mansion and the gardens, the most notable being the construction of terraces leading down to the river front which were completed in 1902 in memory of his mother.

On the dissolution of Gresley Priory in 1543 the buildings were sold to Henry Criche, a speculator in monastic properties. Thirteen years later they were purchased by Sir Christopher Alleyne, son of Sir John Alleyne, twice Lord Mayor of London. Sir Christopher, who had property in Kent, married a daughter of Sir William Paget, who had acquired the monastic properties of Burton Abbey, and possibly this influenced his purchase of Gresley Priory.

He pulled down the Priory buildings, except for the church, and used the material to build a residence known as Gresley Hall. There is no foundation for the belief that the Hall was connected to the Priory by an underground passage.

It would appear the Hall was rebuilt in the Flemish style in the early 18th century and it has some interesting architectural features which have been carefully preserved.

On the death of Samuel Alleyne in 1734 the property passed into the possession of the Meynell family. It was purchased by Sir Nigel Gresley in 1775 and the outbuildings were converted into a pottery in 1794. Gresley Hall was sold by Sir Roger Gresley in 1828 and was converted into a farmhouse and subsequently became a tenement building.

After changing hands several times it was purchased by the National Coal Board in 1953 and converted into a Miners’ Welfare Club. In 1957 the premises were extended to cater for five collieries in the district.

That there was a chapel at Drakelow in the 12th century is proved by a grant to Burton Abbey of the ‘vil’ and church at Stapenhill together with the chapels and tithes of Drakelow, Heathcote and Newhall. This grant was confirmed by Pope Lucius III in 1185. The sites of these three chapels are not known for none was in existence in the 16th century.

In 1650 a Parliamentary Commission stated that: “Drakelow supposed to be a member of Stapenhill is lately united to Gresley and fit so it continue”. The Gresley family always maintained a close connection with Gresley priory from the date of its foundation and the nomination of the Prior was in their hands.

After the Dissolution the Priory buildings were demolished and the nave of the monastic church became the parish church of Gresley and the family association was continued. Although Gresley Church has undergone considerable alterations at different times, it still contains many memorials of the Gresley family, the most notable being an ornate alabaster tomb erected to the memory of Sir Thomas (second baronet) who died in 1699. Under an arch in the centre kneels a life-sized figure of the baronet and round the tomb are impaled the arms of every marriage of his ancestors.

Following the establishment of the Netherseale branch at the beginning of the 18th century, several members have been Rectors of Seale and there are various family memorials in that church. Sir Robert (11th baronet) worshipped at Caldwell Church and is buried there while Sir Nigel, the L.N.E.R. engineer, is buried at Netherseale.

In 1540 Leland wrote: “Sir George Gresley hath upon Trent, a mile lower than Burton, a very large manor place and park at DRAEKELO”. Concerning the park, Sir Robert Gresley (eleventh baronet) wrote: “This park, including the pleasure grounds and that part called the Warren (in older times known as the Hare Park) is 580 acres in extent of which the deer park comprises 297 acres”, It may be of interest to note that the coneygreave or rabbit warren is mentioned in a deed dated 1328.

The deer park was well wooded and contained some fine old trees, a notable feature being the “one mile avenue”, a double row of trees leading to the Hall from a thatched entrance lodge on the Walton Road. There was a large pond in the park and a curious castellated cottage occupied by a gamekeeper.

In addition to a number of Galloway cattle there was a herd of 160 fallow deer, the average weight of a buck being 84 lbs. When the timber was felled in 1934 the remaining deer escaped to the woods where they were eventually killed off.

Burtonians of an older generation will remember with delight the pleasant walk by the riverside from Stapenhill which crossed the Burton-Leicester railway and continued through a meadow into a spinney over a brook crossed by a narrow wooden bridge. Thence a path through the park led to the lodge on the Walton Road.

DRAKELOW AFTER THE GRESLEYS

The contents of Drakelow Hall were sold in July, 1931, and with the consent of the auctioneers I had the privilege as president-elect of Burton Natural History and Archaeological Society, of taking a party of members around the Hall before the sale took place.

There were many panelled rooms with antique furniture, china, etc., and also a tapestry room. Five oaken beds dated from the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I and James I, while two early 17th century ebony beds were probably brought back from Spain by Walsingham Gresley (1585-1633) who was attached to the British Embassy in Madrid.

There were several pieces of armour and various weapons and a notable exhibit was a contemporary model of a 74-gun ship of the early 18th century, possibly the model of a ship in which Sir Nigel (sixth baronet) served. A valued heirloom was the Gresley Jewel, a fine specimen of the 16th century work in the form of a pendant, presented by Elizabeth I to Catherine Sutton, daughter of Lord Dudley, on the occasion of her marriage to Sir George Gresley, K.B.

There were many family portraits from the 16th century onwards as well as numerous other paintings. Many of these portraits are reproduced in the de-luxe edition of ‘The Gresleys of Drakelow’, by F.C. Madan (1899).

Following the sale of the contents of the Hall, an attempt was made to turn the Hall and park into a country club under the auspices of the Automobile Racing Association. It was proposed to open a “junior” road circuit of about three miles in the park by Whitsuntide, 1932, a further eight-mile circuit to be established later for motor racing.

Following the sale of the contents of the Hall, an attempt was made to turn the Hall and park into a country club under the auspices of the Automobile Racing Association. It was proposed to open a “junior” road circuit of about three miles in the park by Whitsuntide, 1932, a further eight-mile circuit to be established later for motor racing.

The Hall was to become an A.R.A. country club house, the existing gardens and woodlands to be preserved in their original state. Tennis courts, a bowling green and a bathing pool were to be constructed while there would be boating and fishing facilities on a two and a half mile stretch of the River Trent with rights over a further one and a half miles of the river, giving a total stretch almost equal in length to the Boat Race course, where races and regattas could be held.

The mansion was to be altered to provide dining rooms, lounges, billiards rooms, card rooms, writing and reading rooms, a cocktail and other bars, tea rooms, dressing rooms, a gymnasium with skilled attendants of both sexes, and hairdressing salons.

There would be residential facilities, for there were already 14 bedrooms and nine bathrooms, in addition to those reserved for the staff.

Some of the stabling was to be retained for use as a riding school and two coach houses would be turned into squash racquet courts. The construction of an indoor lawn tennis court in the stable yard was under consideration and it was proposed to lay out an 18 hole golf course in the park.

For all these facilities ordinary membership would cost £5 5s 0d. p.a., while life membership could be purchased for £52 10s 0d An associate membership however, would cost only £1 1s (one guinea) p.a.

The official opening of the club was arranged to take place on Whit Monday (May 16th) 1932, and the attractions included a motor cycle dirt-track of 1,000 yards on which ‘Cannon Ball’ Baker would set up the first record. A motor cycle gymkhana was to be arranged by the Burton Motor Cycle and Light Car Club, and there were equestrain competitions and a boxing display.

The ground and Hall were open to the public on payment of 1s 3d but Whit Monday, 1932, proved to be a very wet day. The attendance was poor and the scheme proved a failure, the “Country Club Company” being evicted from the premises on 16th July, 1932.

The outlying portions of the Drakelow Estate which covered 707 acres, were sold on 19th January, 1933, and the remainder, including the “stately Elizabethan Mansion and magnificently timbered deer park” was offered for sale at the Queen’s Hotel on December 19th, 1933. The auctioneers stated that the Hall, though mainly Elizabethan in character, had been altered and restored at different periods but never actually rebuilt.

The accommodation on the ground floor included an entrance hall, 45 ft. by 18ft., with oakpanelled walls and a marble fire place, a tapestry room, 38ft. by 17ft. 6ins., with mullioned window and a corridor to a china lobby with Jacobean oak panelled walls. The windows of the breakfast room contained coats of arms in stained glass and the oak panelled walls are enriched with armorial bearings. The music room, 32ft. by 18ft., had pine panelled walls and doors of walnut with walnut burr panels. The walls of the drawing room were covered with fine green silk damask and there was a superb mantel piece of white marble and Blue John. There was also an oak panelled study and billiards room with mullioned bay windows containing glass coats of arms.

The most interesting feature of Drakelow Hall was undoubtedly the dining room known as the ‘Painted Room’. This was a room painted in the 18th century with a continuous landscape to create the illusion that the visitor was not in a room at all but outside, surrounded with picturesque scenery. A cornice was replaced by a coved ceiling which enabled the artist to run his trees up into an open sky, and real trellis work was set around the room and its apertures while the fireplace was disguised as a grotto.

The paintings represented scenery in the Peak district and were attributed to Pauly Sandby. Anna Seward, the ‘Swan of Lichfield’, who visited the Hall in 1794, thus described her impressions:

“Sir Nigel hath adorned one of his rooms with singular happiness. One side is painted with forest scenery whose majestic trees arch over the coved ceiling. The opposite side represents a Peak valley, while the front shows a prospect of more distant country. The chimney piece represents a grotto formed of spars, ores and shells. Read palings, breast high and painted green, are placed a few inches from the walls and increase the deception. In these are little wicket gates that half open, tempt the visitor to ascend the forest banks”.

It is pleasing to add that this room is now preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

An old oak staircase rising in two flights and lit by a lofty arched window containing stained glass coats of arms of the Gresley family led to ten principal bedrooms, five bathrooms, a boudoir and dressing room, all of which were on the first floor. There were also 14 bedrooms and two bathrooms on the second floor.

The domestic offices on the ground floor included a large kitchen scullery, butler’s pantry, butler’s bedroom, housekeeper’s sitting room, kitchen maid’s room, two valets’ rooms, bathroom, larder, game larder, two still rooms, laundry and dairy.

The outbuildings included store rooms, game larders and brewhouse, while a detached block of stable buildings comprised three loose boxes, stabling for 21 horses, a saddle room and a heated garage, together with a gardener’s cottage.

The estate was purchased by Sir Albert Ball, of Nottingham, in conjunction with Messrs, Marshall Bros. (Timber Merchants) Limited, for £12,500.

The extensive pleasure grounds adjoining the Hall were surrounded by a protective belt of trees and some of the hollies and yews were trimmed to a height of thirty feet. There were several separate small gardens and pleasaunces which were probably laid out in the 18th century.

The extensive pleasure grounds adjoining the Hall were surrounded by a protective belt of trees and some of the hollies and yews were trimmed to a height of thirty feet. There were several separate small gardens and pleasaunces which were probably laid out in the 18th century.

Of these the most notable was the round garden, in the middle of which was a circular stone edged basin with a central fountain in the form of a mermaid blowing water through a conch or shell. This old garden was improved by Sir Robert Gresley (eleventh baronet) who placed the fountain there. There were also several large stone vases filled with flowering plants.

In another garden, four wide grass walks converged upon a small stone basin also ornamented with a fountain. There was also a long box garden and a walled rose garden laid out in the reign of William III. The ‘temple’ at the end of the rose garden was built from the designs of Reginald Bloomfield, author of “The Formal Gardens of England”. Paintings of these gardens by Beatrice Parsons (1905) are still in existence. All the gardens were quite separate and at one time a staff of 30 gardeners was required for their maintenance.

In January, 1934, Drakelow Park and Warren Farm were purchased from Sir Albert Ball and Messrs. Marshall Bros, by Mr. C.F. Gothard of Bearwood House, Burton-on-Trent, who as a boy had been permitted by the Gresley family to ride in the park and fish the river Trent where it passed through the Drakelow estate of which he thus acquired pleasant memories.

The hall was carefully examined to see if any part of it could be modernised and made habitable, but acting upon expert advice it was decided that the mansion would have to be demolished and this was done.

Mr. Gothard also purchased separately the Barn Farm and the Grove Farm with outlying woods and other land, so that with his purchase of the park, Warren Farm and adjacent woodlands, almost the whole of the former Drakelow estate as it stood after the first World War passed into his possession.

Extensive stabling premises and other outbuildings forming the coach yard of the hall were left standing and part of this block, comprising mainly some of the harness rooms, was converted into a farm house by the new owner who was interested in farming, the preservation of wild life and also in game and wildfowl shooting. In course of time he hoped to take up farming on a larger scale, to build a small modern house near the site of the hall, and to beautify the banks of the river with flowering trees and shrubs. He farmed the whole of the park during the 1939-45 Second World War, but unfortunately the prospective development plans did not come to fruition.

In 1933, there was an attempt to sell Drakelow Hall and its estates as a set of separate lots, the sales brochure of which can be seen in the ‘For Sale’ section, but the sale was unsuccessful. There followed, an unsuccessful attempt to turn it into an exclusive country club. Like many of Burton’s surrounding stately homes, it was demolished shortly afterwards.

Drakelow Park and Warren Farm were eventually acquired by the British Electricity Authority in 1950 to become the site of Drakelow Power Station.

In Tudor times, William Paget was one of the most prominent men in England. Son of John, one of the serjeants-at-mace of the city of London, he was born in London in 1506. His father was said to have been of humble origin from Wednesbury, Staffordshire. Educated at St Paul’s School, and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, proceeding afterwards to the university of Paris.

In Tudor times, William Paget was one of the most prominent men in England. Son of John, one of the serjeants-at-mace of the city of London, he was born in London in 1506. His father was said to have been of humble origin from Wednesbury, Staffordshire. Educated at St Paul’s School, and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, proceeding afterwards to the university of Paris.

The site was in an orchard adjoining the former Warren Farmhouse and the “find” consisted of a small jar or bowl, globular in shape, with a base diameter of one and a half inches, and a height of two and a half inches. Made of well-fired grey-brown ware, it had a stamped decoration of horse shoes around the neck with incised chevrons and square stamps enclosing a cross on the body.

The site was in an orchard adjoining the former Warren Farmhouse and the “find” consisted of a small jar or bowl, globular in shape, with a base diameter of one and a half inches, and a height of two and a half inches. Made of well-fired grey-brown ware, it had a stamped decoration of horse shoes around the neck with incised chevrons and square stamps enclosing a cross on the body.

Another notable member of the family was Sir Herbert Nigel Gresley, C.B.E., D.SC, M.I.C.E., M.I.MECH.E., M.I.E.E. shown here. He was born in 1876 he was the fourth son of the Rev. Nigel Gresley (9th baronet) and nephew of Sir Thomas Gresley (10th baronet) and cousin of Sir Robert Gresley (11th baronet).

Another notable member of the family was Sir Herbert Nigel Gresley, C.B.E., D.SC, M.I.C.E., M.I.MECH.E., M.I.E.E. shown here. He was born in 1876 he was the fourth son of the Rev. Nigel Gresley (9th baronet) and nephew of Sir Thomas Gresley (10th baronet) and cousin of Sir Robert Gresley (11th baronet).

Following the sale of the contents of the Hall, an attempt was made to turn the Hall and park into a country club under the auspices of the Automobile Racing Association. It was proposed to open a “junior” road circuit of about three miles in the park by Whitsuntide, 1932, a further eight-mile circuit to be established later for motor racing.

Following the sale of the contents of the Hall, an attempt was made to turn the Hall and park into a country club under the auspices of the Automobile Racing Association. It was proposed to open a “junior” road circuit of about three miles in the park by Whitsuntide, 1932, a further eight-mile circuit to be established later for motor racing. The extensive pleasure grounds adjoining the Hall were surrounded by a protective belt of trees and some of the hollies and yews were trimmed to a height of thirty feet. There were several separate small gardens and pleasaunces which were probably laid out in the 18th century.

The extensive pleasure grounds adjoining the Hall were surrounded by a protective belt of trees and some of the hollies and yews were trimmed to a height of thirty feet. There were several separate small gardens and pleasaunces which were probably laid out in the 18th century.

EARLY HISTORY

EARLY HISTORY

The Milligans

The Milligans Although Eva was the eldest, it was Blanche who was the best known and most dominant figure and in later years, was rarely seen out without her faithfull dog ‘Ben’; the two of them can be seen in the photograph on the right.

Although Eva was the eldest, it was Blanche who was the best known and most dominant figure and in later years, was rarely seen out without her faithfull dog ‘Ben’; the two of them can be seen in the photograph on the right.