Edward Wightman of Burton-on-Trent was the last person to be executed by burning at the stake for heresy in England in 1612.

Early Life

Edward was born at Burbage, Leicestershire in 1566. He was the son of a schoolteacher and draper (cloth trader) but during his childhood he moved to Burton-on-Trent where he was educated at Burton Grammar School. After initially working in his mother’s drapery business, Edward was apprenticed by a wool cloth trader in Shrewsbury. Edward’s parents were members of the traditional Church of England with no known separatist or puritan leanings but, whilst in Shrewsbury, he became involved with, and strongly influenced by, a group of puritans headed by John Tomkys. The radical brand of Protestantism included the rejection of the trinity and the divinity of Jesus Christ as well as a complete rejection of the institutionalized Church of England. This would have been extremely dangerous in Tudor times, but still pretty thin ice in the times of James I.

Edward was born at Burbage, Leicestershire in 1566. He was the son of a schoolteacher and draper (cloth trader) but during his childhood he moved to Burton-on-Trent where he was educated at Burton Grammar School. After initially working in his mother’s drapery business, Edward was apprenticed by a wool cloth trader in Shrewsbury. Edward’s parents were members of the traditional Church of England with no known separatist or puritan leanings but, whilst in Shrewsbury, he became involved with, and strongly influenced by, a group of puritans headed by John Tomkys. The radical brand of Protestantism included the rejection of the trinity and the divinity of Jesus Christ as well as a complete rejection of the institutionalized Church of England. This would have been extremely dangerous in Tudor times, but still pretty thin ice in the times of James I.

In 1590, he was admitted as a master into the Shrewsbury Drapers’ Company, but within a few years, he returned to Burton-on-Trent to start a clothing business. He married Frances Darbye in 1593. They produced 2 sons and 5 daughters.

When Edward returned to Burton, the religious mood had changed quite dramatically from his childhood days there when religion in the town was dominated by the local noble, Lord Paget who still promoted Roman Catholicism.

In 1583, during the interim period, Lord Paget had fled England after ending up on the losing side of some political plotting involving Mary, Queen of Scots. Henry Hastings emerged as the new local noble and political leader, and he was a committed Protestant. Under his leadership, a new evangelical puritanism emerged in Burton. Peter Eccleshall, the Burton curate, was indicted in 1588 for not using the Book of Common Prayer. A puritan evangelist, Philip Stubbes, lived in Burton for a time during the early 1590’s, thus a modest form of puritanism quickly became well-established in Burton.

The clothiers and various influential business people in Burton were very much involved in the religious transformation so Edward’s turn to puritanism was part of a town-wide trend. In 1595, Lord Hastings died, and William Paget, son of the previous noble, was reinstated in the lands of Burton. Despite Paget’s establishment as Baron in 1604, he spent little time in the Burton area so there was no reverse of evangelical puritanism in the town. This paved the way for Edward eventually becoming a radical ‘lay leader’ in the religious community.

Stapenhill Witch

In February 1596, at a time when the country was obsessed with witchcraft, thirteen year old Thomas Darling accused Alice Goodridge of Stapenhill of being a witch and possessed him with a devil. Young Thomas exhibited the classic ‘Exorcist’ symptoms such as vomiting, paralysis, and hallucinations. During his fits of spiritual possession, he would apparently be possessed by the devil one moment and the Holy Spirit the next.

The new puritan minister in Burton, Rev. Arthur Hildersham, became interested in the case, and prayed with Darling, but was unable to exorcise the boy’s demons. Another puritan minister, Rev. John Darrell, who came from nearby Ashby-de-la-Zouch was finally able to exorcise Darling and drive off his possessor.

Alice Goodridge was jailed in Derby and interrogated at Burton town hall in May 1596. Under pressure, she confessed. Many who knew of the Darling case were not convinced of the truth of the boy’s possession. It soon became a symbol in the growing political struggle between the puritan and Anglican communities. The Burton puritans sought to document and prosecute the case aggressively.

Edward Wightman took a strong interest in the Darling case and when Alice Goodridge was interrogated in Burton, Edward was one of five men who ‘examined’ her showing that he was an important and well-respected public figure and religious authority. He was actively involved in documenting the boy’s possession and involved in the ecstatic prayers associated with the boy’s exorcism. The testimonials on the truth of the boy’s claim included the signatures of Edward, Rev. Eccleshall, most of the Burton clothier community, and many established and well-connected local individuals.

The case demonstrates Edward’s highly emotional and spiritual brand of puritanism and his position of authority and leadership despite his relative youth. His involvement in the Darling case proved a turning point in his life, making him entirely amenable to the possibility of unmediated spiritual intervention. Darling claimed not just to be possessed by the devil, but engaged in a series of ‘spiritual wars’ in which both demonic and angelic voices were said to emanate from him.

In the wake of the Darling case, there was a significant backlash against the puritans. Rev. Darrell, the minister who had finally succeeded in exorcising the boy, was convicted of fraud and went into hiding. The practice of group exorcisms was suppressed and soon afterwards died out.

Edward the Radical

Partly through circumstance, Edward was driven to an even more radical separatism. In the late 1590s, England suffered a severe economic downturn after a series of very bad harvests, and several bad aspects of the economy. The cloth trade was particularly badly hit and Edward’s business pursuits failed. By 1603, Edward had purchased an alehouse in Burton and was now a simple tavern keeper, impoverished and deeply in debt. His financial standing had taken a disastrous turn, close to ruin. His swift rise to prominence in Burton society during the 1590s followed by almost as fast a fall fuelled his religious extremism.

Edward was also involved in a court case over a dispute between him and his former apprentice, Samuel Royle, from November 1600 through January 1601. For whatever reason, Edward apparently failed to appear before the court in January 1601, which may have cost him a 40 pound bond. The loss of that sizeable sum might have finished Edward off in the clothing business. The justice who handled the Royle v Wightman dispute was Sir Humphrey Ferrers, and later events suggest that Edward harbored ill feelings toward the noble.

Despite Edward’s legal and financial woes, it is apparent that he retained some degree of significant stature among the new leading puritans in Burton and still closely associated with key figures in Burton’s religious society. They apparently thought well of him and perhaps still looked to him for religious leadership.

The first documented evidence of Edward’s descent into extremism came in early January 1608. Sir Humphrey Ferrers had recently died and Edward was entertaining company in his own home. The conversation turned to Ferrers’ death and Edward’s grudge against him from the 1601 case that may have helped precipitate Edward’s ruin. Edward stated to the assembled company that he believed that the soul does not leave the body upon death, but rather stays with the body until Judgment Day, at which point it either ascends to heaven or descends to hell. Though not too shocking now, this would have been shockingly heretical at the time.

Edward became more vocal about his view of the nature of the soul and death. He continued to argue the point with local clergy. Curate Henry Aberley of Burton opted to use his own pulpit to argue against such heretical ideas, but this apparently led to bitter, and sometimes public, arguments with Edward. As a result, Edward stopped attended the Burton parish church and began worshipping elsewhere.

Despite Edward’s theological split with the established religious community, he was not abandoned by religious leaders. This is consistent with the behavior of other puritanical communities in response to other heresies. Instead of prosecuting or excommunicating the errant individual they would try to reform his views. Chief among those who engaged Edward was Burton puritan minister Rev. Arthur Hildersham, who had probably played a major role in Edward’s ascendance in the religious community a decade earlier.

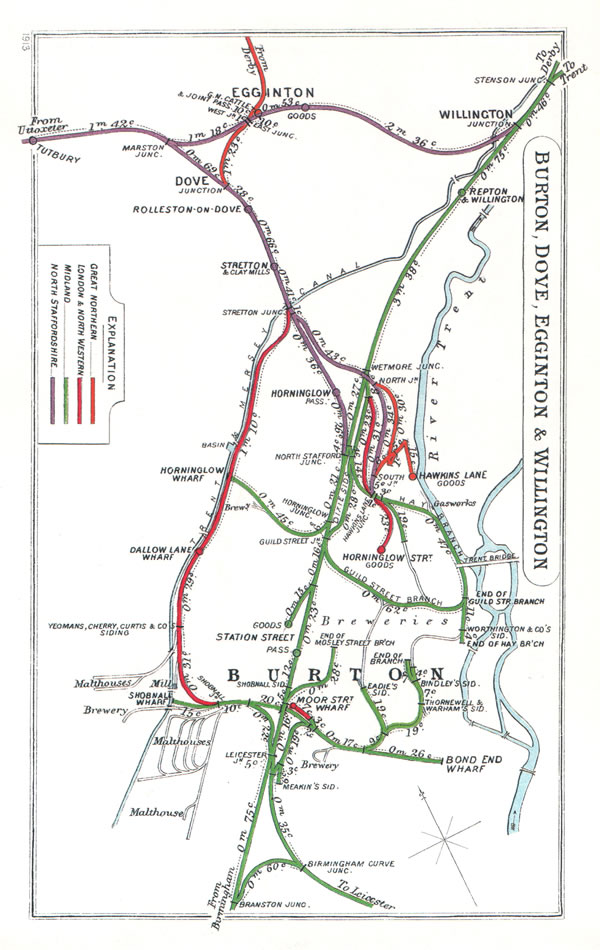

Hildersham, and Rev. Simon Presse of Egginton, Derbyshire, met with Edward privately and attempted to convince him to change or moderate his view. The obstinate Edward refused and Hildersham ultimately responded by preaching against Edward’s heretical views from his Burton pulpit on March 15, 1609. Hildersham continued to correspond with Edward for a time, but eventually tired of Edward’s stubbornness and cut off the debate. Edward apparently interpreted this as a victory and became all the more convinced of the righteousness of his heterodoxy.

From 1609 to 1611, the process of engaging and attempting to ‘correct’ Edward’s view continued, but Edward became increasingly radicalized and spent his energies writing manuscripts outlining his views. He was a prolific writer, although none of his writings have survived. He was known to never leave home without a number of his books which he read and preached to anyone who would listen. Edward was only ever a ‘lay leader’ in the religious community and never held an official ministerial position. Although enjoying a number of followers for a time, by 1611 he was increasingly avoided and eventually became something of a loner.

King James I Condemnation

King James I Condemnation

England had become a relatively tolerant nation under Elizabeth I but the religious and political situation changed when James I took the throne in 1603. Although King James was tolerant toward Catholics and helped liberalize the Church of England, with the famous English translation of the bible bearing his name, he saw Protestant dissenters, such as Puritans, Baptists, and Quakers, as a major problem and challenge. Among James’ great religious interests was support of catholic orthodoxy, which includes adherence to the major creeds. He took his title of ‘Defender of the Faith’ seriously and since 1607 he had been engaged with Roman Catholics over the ‘Oath of Allegiance’. Edward’s views were therefore, very much opposed to the King’s view.

Wightman set about putting together a compendium of his theology for his upcoming hearing and defense. Perhaps thinking that he would at least be allowed time to plead his case, he delivered copies of it to members of the clergy in an effort to gain support.

Now completely deluded, believing in his own righteousness and persuasiveness, he delivered a manuscript detailing his radical theology (thought to have originally been intended for Anthony Wotton) to King James I despite being fully aware of the King’s religious stance. This was a dubious move to say the least, particularly since the King had recently ordered the execution of Bartholomew Legate for heresy.

The manuscript consisted of eighteen leaves (pages). To give a flavour, it began, “A letter written to a learned man to discover and confute the doctrine of the Nicolaitanes very mightily defended with all the learned of all sorts, and most of all hated and abhorred of God himself, because the whole world is drowned therein: And seeing he hath promised to answer he knew not to what, and least he should also deal with me as the men of that faction have done already…”. The document concluded, “… and say glory be to God alone which dwelleth in the high heavens, whose good will is such towards men that he will now at the last, plant peace on the earth, and let all people say, Amen”. You may be relieved to know that almost the remainder of the document has not survived.

In February 1611, Edward interrupted Lent worship services in Burton with loud outbursts. It took significant effort to get him to quiet down. Finally, the Burton religious community had had enough. The Burton minister involved and others from Burton presented the case against Edward at the ecclesiastical visitation of Bishop Richard Neile of Westminster within a few weeks of Edward’s February 1611 disruptions. In early March 1611, Edward was summoned by Neile to Curborough, near Lichfield. Neile promptly returned to London and reported his findings to King James. The King was set on dealing with this troublesome heretic.

In April 1611, by order of the King, local church authorities issued a warrant for his arrest. The order instructed the church constables of Burton to immediately take him before Bishop Richard Neil at the Consistory Court at Lichfield Cathedral for interrogation of his religious views and for conformation to the established Anglican order. Neile’s Chaplain, who assisted in prosecuting Wightman, was William Laud, the future Archbishop of the Church of England, who was later executed himself!

The Trial

The first day of the trial was held on November 19, 1611. On the second day of the trial on November 26, the crowd was so large that the trial had to be moved to the larger space of the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin. On December 5, Edward was brought before the court for his final appearance. Throughout the trial, Edward did not attempt to defend himself. Instead, he attempted to educate them on the righteousness and intellectual rigor of his arguments, ‘clarifying’ the court’s conception of his heresies.

Sentence was pronounced on December 14, 1611. The charges brought against him included eleven distinct heresies. Part of the charge was that he believed “that the baptizing of infants was an abominable custom; that the doctrine was a total fabrication and that Christ was only a mere man and not the son of God; that the Lord’s Supper and baptism were not to be celebrated; and that Christianity was not wholly professed and preached in the Church of England, but only in part.” Other charges included several equally radical opinions.

After months of being subjected to a series of conferences with ‘learned divines’, Wightman was finally brought before Bishop Neil for the last time. Having refused to change any of his views, he was sentenced to be excommunicated and condemned to be burned at the stake following approval by King James I. Prior to his execution, he was to be placed in a public open place as an example to others who might harbour similar beliefs.

The Execution

When the execution day arrived on March 20, 1612, Edward was tied to a post on the square in Lichfield next to Saint Mary’s church and the fire was lit under him. On feeling the heat, Edward screaming out in recantation and he was pulled down, already badly burned. A written retraction was hurriedly prepared and Edward, in pain and weakness, orally agreement as it was read to him. Later, however, no longer fearing the flames, he refused to sign the retraction and blasphemed louder than before.

King James re-approved his execution and a few weeks later on April 11th, he was once more led to the stake. Once again, on feeling the intense heat of the fire, Wightman cried out in recantation again but this time, the sheriff told him he would cost him no more and commanded more faggots (bundles of thin sticks) to be thrown on to make the flames roar. Edward was burned to ashes.

Conclusion

Seeing that heresy still survived with a number of religious radicals still emerging, King James I lost faith in burning heretics. After the case of Edward Wightman, it was decided that those found guilty of heresy should instead silently and privately waste away in prison rather than excite others with a public execution.

It was not until 1677 that an act of Parliament expressly forbade the burning of heretics, securing once and for all, Wightman’s dubious position in history as ‘The last person in England to be burned at the stake for heresy’.

Edward was born at Burbage, Leicestershire in 1566. He was the son of a schoolteacher and draper (cloth trader) but during his childhood he moved to Burton-on-Trent where he was educated at Burton Grammar School. After initially working in his mother’s drapery business, Edward was apprenticed by a wool cloth trader in Shrewsbury. Edward’s parents were members of the traditional Church of England with no known separatist or puritan leanings but, whilst in Shrewsbury, he became involved with, and strongly influenced by, a group of puritans headed by John Tomkys. The radical brand of Protestantism included the rejection of the trinity and the divinity of Jesus Christ as well as a complete rejection of the institutionalized Church of England. This would have been extremely dangerous in Tudor times, but still pretty thin ice in the times of James I.

Edward was born at Burbage, Leicestershire in 1566. He was the son of a schoolteacher and draper (cloth trader) but during his childhood he moved to Burton-on-Trent where he was educated at Burton Grammar School. After initially working in his mother’s drapery business, Edward was apprenticed by a wool cloth trader in Shrewsbury. Edward’s parents were members of the traditional Church of England with no known separatist or puritan leanings but, whilst in Shrewsbury, he became involved with, and strongly influenced by, a group of puritans headed by John Tomkys. The radical brand of Protestantism included the rejection of the trinity and the divinity of Jesus Christ as well as a complete rejection of the institutionalized Church of England. This would have been extremely dangerous in Tudor times, but still pretty thin ice in the times of James I. King James I Condemnation

King James I Condemnation

Bass, founded by William Bass in 1777, is one of the most successful brewing companies of all time. When the London Stock Exchange established the original FT 30 index in 1935, listing the top 30 UK companies, Bass was included in the list.

Bass, founded by William Bass in 1777, is one of the most successful brewing companies of all time. When the London Stock Exchange established the original FT 30 index in 1935, listing the top 30 UK companies, Bass was included in the list.

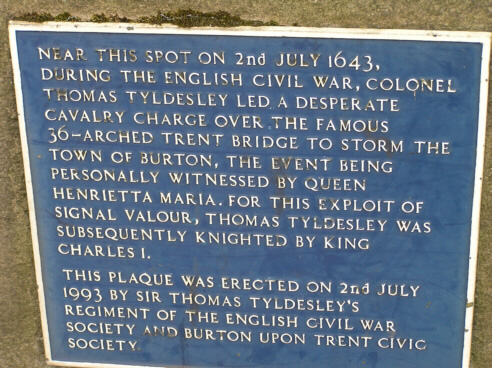

The English Civil War started in 1642 when Charles I (pictured) raised his royal standard in Nottingham. England was split between those that supported the King and those that supported Parliament. In the case of Burton, support was fairly strongly parliamentarian. One of the most prominent Burton paliamentarian was Daniel Watson of Nether Hall. Before the outbreak of the civil war, he was a lawyer but he became a captain of dragoons in the Derbyshire cavalry.

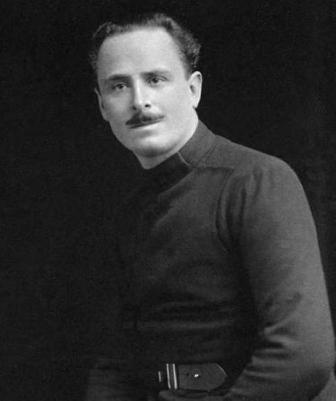

The English Civil War started in 1642 when Charles I (pictured) raised his royal standard in Nottingham. England was split between those that supported the King and those that supported Parliament. In the case of Burton, support was fairly strongly parliamentarian. One of the most prominent Burton paliamentarian was Daniel Watson of Nether Hall. Before the outbreak of the civil war, he was a lawyer but he became a captain of dragoons in the Derbyshire cavalry. On 4th July, 1643, that garrison was stormed in what was probably the most famous local battle of the war – ‘The Battle of the Bridge’. An army under Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I, was commanded by Thomas Tyldesley (pictured), a supporter of Charles I and a Royalist commander from Lancashire, at the time having the rank of Colonel, led a cavalry charge across the bridge to attack Burton. It was a very bloody confrontation in which the church was damaged and the town was, according to Gell, “most miserably plundered and destroyed”. At the end of the battle, so much booty was taken that the Queen, who witnessed the battle, recorded that her soldiers “could not well march with their swollen bundles”.

On 4th July, 1643, that garrison was stormed in what was probably the most famous local battle of the war – ‘The Battle of the Bridge’. An army under Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I, was commanded by Thomas Tyldesley (pictured), a supporter of Charles I and a Royalist commander from Lancashire, at the time having the rank of Colonel, led a cavalry charge across the bridge to attack Burton. It was a very bloody confrontation in which the church was damaged and the town was, according to Gell, “most miserably plundered and destroyed”. At the end of the battle, so much booty was taken that the Queen, who witnessed the battle, recorded that her soldiers “could not well march with their swollen bundles”.