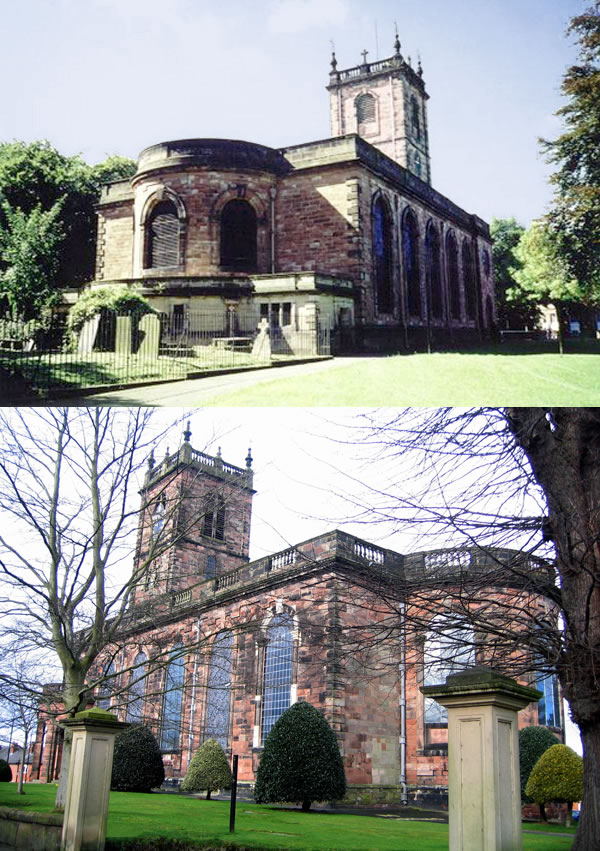

Present Saint Modwen’s Church

Saint Modwen’s Church was built between 1719 and 1728 but the church history goes back very much further. The present church stands on the site of the church of the Benedictine Abbey founded in 1002 by Wulfric Spot. The abbey had a very large cathedral-like church which served both the monks and the people of the town. After the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII, Burton Abbey was one of the very few that was not destroyed.

Over the next two centuries, it gradually fell into disrepair and disappeared as its stone was pillaged for other building work. Eventually, all that remained was the abbey church which continued to be used as a parish church, which can be seen in the below footprint. In its heyday, the enormous abbey extended down to include the current building labelled as The Abbey on the map.

By 1718, this too had become dilapidated and unsafe and it was decided to demolish it and build a replacement. The architect and builder William Smith, and his brother Richard, of Tettenhall were appointed by the parish vestry to build the new church. Smith had already worked on the impressive Saint Mary’s Church in Warwick and had built the church of Saint Alkmund in Whitchurch, Shropshire which was of very similar design. He was one of the most experienced church builders in the Midlands.

It was designed in a Classical style by the brothers Richard and William Smith of Tettenhall. The same design as Saint Alkmund’s was used which was based on a design of John Barker which itself was based on ideas by Sir Christopher Wren.

Work on the new church started in 1719. Their first job was to fit up a building known as the High Hall, which stood in the Market Place, for worship while the abbey came down and the new church was built. Unfortunately, neither William or Richard Smith lived to see the church completed; William died in 1724 and Richard in 1726. The church was completed by their younger brother Francis – ‘Smith of Warwick’, who had by now become more famous. He oversaw the completion of the church and addition of the churchyard walls. It was finally completed in 1928.

The church itself is built in red sandstone and comprises an aisled five-bay nave with galleries on the north, west, and south, an apse, and a western narthex with central tower, north and south gallery stairs, and internal porch. The west tower is of three stages and has a balustrade with urns and round windows with radial glazing bars. The apse has wide Doric pilasters at the opening and between the windows. The nave arcades have tall Doric piers without an entablature, the flat ceiling has a deep cove, and there are nave galleries cut across the high, arched windows of the aisles. The church retained its original altar rails and gated pews.

The main tower is 92 feet high to the parapet, over 100 feet to the top of the four vanes.

Churchyard

In the mid 16th century the graveyard lay to the south of the church. A lychgate mentioned in 1568 may be the church stile of 1682, and stone left over from the rebuilding of the church was used in 1727 to make a churchyard wall encompassing land to the south, east, and north of the church. In 1829 a railing fence was put up in front of the church. The same year the vestry leased land called the Arbour on the north side of the churchyard as an additional burial ground, and in 1830 an adjoining 1.5 acres was leased from the marquess of Anglesey.

In 1835 the churchyard covered 3 a. 25 p. New burials were restricted from 1856, and the churchyard was closed in 1866 when the municipal cemetery was opened. That part of the churchyard north of the church was vested in Burton corporation in 1939, and was converted in 1952 into a garden of remembrance for Burtonians who had died in the Second World War.

Alabaster Figure

An alabaster figure of a knight, dating from the late 15th or early 16th century, lay under the tower of the abbey church. Although already damaged, it was though important enough to preserve and move into the new church. When the church was completed, it stood under the west tower. Much admired, it was moved in the mid 19th century to a position where it could be clearly viewed from the market place.

By 1878 it had been moved to the garden of the Priory, a house in the south-west corner of the former monastic cloister. In 1924, it was presented to Burton museum but, when the museum was closed, like numerous items of Burton’s heritage, it mysteriously disappeared.

Pulpit

Christopher Wren had recommended that churches were planned so that everyone could see and hear the minister, especially when he was preaching. In accordance with this, the original pulpit was centrally placed. In this central position however, the pulpit completely obscured the Communion table from the rest of the church. That suited Anglican worship of the eighteenth century where communion was rarely celebrated and when it was, communicants would pass beyond the pulpit and gather round the table.

The galleries were part of Smith’s design and the pews are an integral part of the building. The columns stand on plinths that are panelled and integral with the seating. The church can seat over a thousand people in original Georgian pews!

A large chandelier was presented to the church by William Hawkins in 1725, in time for the completion. This, of course, was to be the only available lighting.

Font and Plate

The font has survived from the abbey church. It has an octagonal bowl from the fifteenth century – during the Tudor period. It is one of the few survivals from the medieval church.

The plinth is newer, dating from 1662, and bears the initials of the vicar, Rev. William Middleton) and church wardens of the day. The basin was later lined with lead and is covered by a nineteenth century wooden cover.

The plate in 1549 included two chalices and two patens, but only one of each pair remained in 1552. A silver chalice and paten were acquired in 1662. Anne, wife of Sir Henry Every, gave a paten in 1705, and Mary, widow of Sir Robert Burdett of Bramcote, in Polesworth, Warwickshire, gave a flagon in 1726 when she was living in Burton. In 1727 the minister, William Browne, gave another flagon and his wife Ann gave a paten. A further chalice was acquired between 1795 and 1830.

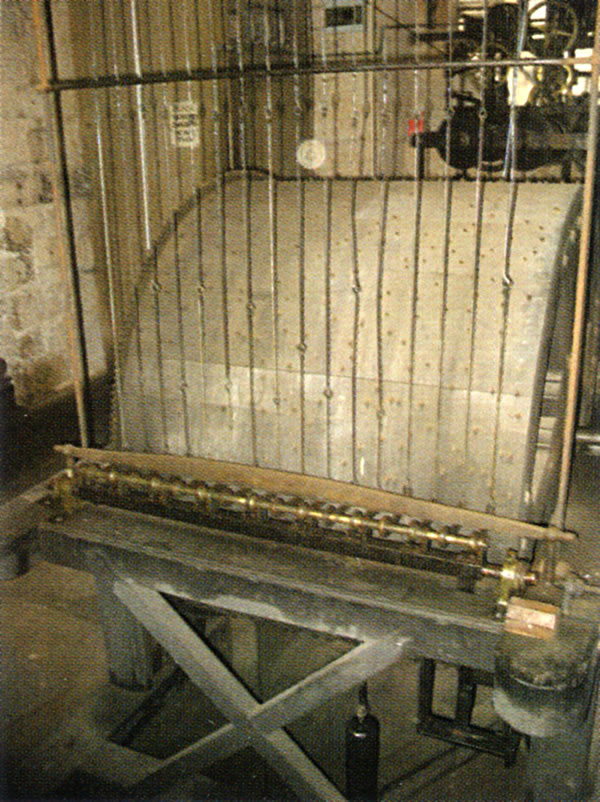

Church Organ

An organ was installed in the west gallery in 1771. It was built by Johann Snetzler who was one of the foremost organ builders of the time. The case was designed by James Wyatt. His design remains in the Royal Institute of British Architects. Iron columns were inserted into the west galley to bear the weight of the organ.

Anthony Greatorex (d. 1814) was appointed organist. His salary was met by public subscription until 1790, when, subscriptions falling off, it was met out of the church rates. Anthony was succeeded as organist by his son Thomas Greatorex (d. 1831), a distinguished musician, although his conducting and playing duties in London must have restricted his ability to perform in Burton. He resigned in 1828 and was succeeded by Charles Yates, who resigned in 1847 after the minister of St. Modwen’s had accused him of immoral conduct and professional incompetence and had employed a police constable to prevent him from playing in services.

A group of church singers under control of the organist was described in 1807 as “a set of industrious, hard working people, some of whom have large families and can ill afford any expense“. Consequently, their costs, estimated at 2 guineas a year, were to be raised by subscription, the Earl of Uxbridge pledged 1 guinea. They were replaced in 1847 by a volunteer church choir.

The cameo panel on the case, perhaps made by Josiah Wedgwood, is thought to represent the composer, George Frederic Handel, whose organ music was highly popular at the time. There is none of Snetzler’s original organ in the church today, although some of the pipes are believed to be in Trinity Methodist Church. The case was extended on each side to accommodate a larger organ which was installed in 1972, built by Hill, Norman and Beard.

An electrically operated organ was installed in 1900.

Clock and Bells

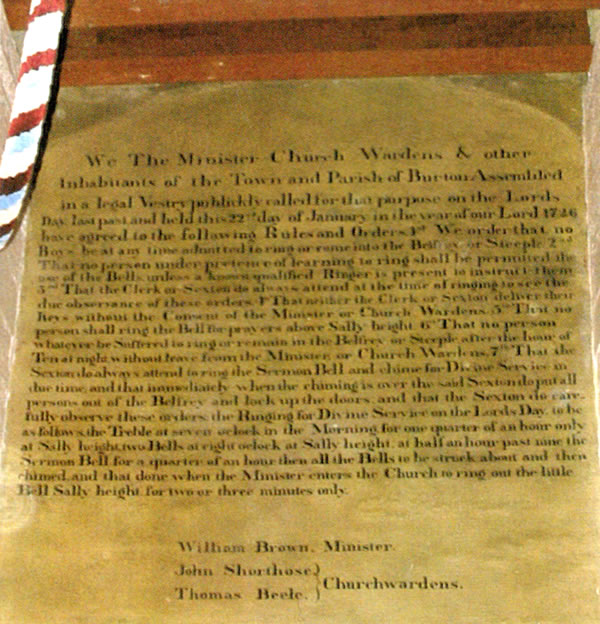

Five bells survived from the previous abbey church. These were re-cast into six in 1725, during the building of the new church, by Abraham Rudhall of Gloucester. The largest tenor bell weighs 18 cwt. Two new small bells were cast at the same time to make a ring of eight bells. The Ringers Rules dating from 1726 are painted on the wall of the ringing chamber. These date from when the bells were installed but before the church was complete.

Despite the conspicuous rules. Disturbances caused by bell ringers led to the adoption in 1727 of rules governing conduct in the belfry: no ringing was allowed after 10 pm and only known and qualified ringers were allowed in the belfry, and only the sexton was to ring for sermons and services.

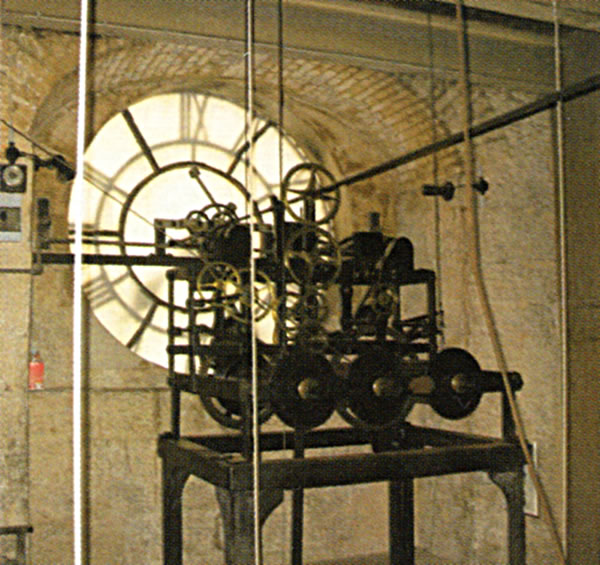

The tower clock was installed in 1785 at a cost of £203, half of which was donated by the Earl of Uxbridge. It was manufactured by the celebrated clock maker, John Whitehurst of Derby. The mechanism controls two clocks through a simple gearbox; one facing the market place, the other facing the memorial gardens.

Also installed at the same time as the clock were eight bells and a Carillon; this resembles a huge musical box with pegs on a rotating drum which depress levers which in turn operate hammers against the bells. The Carillon was installed to play a variety of tunes on the bells at certain times. In the early 20th century the chimes played a different tune on each day of the week. After the Second World War it only chimed on market days. The Carillon remains functional but until recently were only heard on special occasions. In 2010 pleasingly, its use was restored to play a tune every day at midday.

In the early 19th century the ringers were threatened with losing a third of their fee because they would ring only for their own pleasure and not for the church’s services. In 1829 they were paid £7 4s for ringing at services, the appointments of churchwardens, and on national holidays, and between 1829 and 1838 they also received £1 for an annual feast. In 1865 their fee was raised from £10 to £15 a year. In 1895 Francis Charrington gave £60 to pay for the ringing of the bells each year on Trafalgar day (21 October).

Vicarage

In 1808, the minister is known to have had a house in High Street. The minister still resided in High Street in 1851 but some time before 1860, this had moved to a house called Trent Bank at Bond End. This was described in the 1890s as “anything but compatible with the dignity which one associates with the principal minister of the town“.

In 1893 a house called The Orchard in Orchard Street was purchased as a vicarage house with money raised by public subscription and a grant from Queen Anne’s Bounty. That house, which had formerly belonged to Martha Thornewill, mother of the vicar, C. F. Thornewill, was sold to a union of the benefices in 1982 but was demolished in 1989. A new vicarage house was built in Rangemore Street in 1983.

Financial support for an assistant curate was provided by the Additional Curates’ Society from 1844 until 1877, but the bulk of the assistant’s income came from voluntary local contributions. One or occasionally two curates were still employed until 1910; thereafter however, the de-population of the town centre meant that there was no curate until the later 1950s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s the curate lived in the former Christ Church vicarage house in Moor Street, renamed St. Modwen’s House. In 1994 the minister of St. Aidan’s in Shobnall Road, was appointed to serve also at St. Modwen’s as a town centre chaplain.

Parish Division

In 1824 the parish was divided into two districts, a southern one for the church of St. Modwen and a northern one for the newly built Holy Trinity church; the northern area was constituted a separate parish in 1842. Thereafter both parishes were subdivided by the creation of further ecclesiastical districts and parishes: Christ Church (1845); Horninglow (1867); Winshill (1867); Branston (1870); St. Paul’s (1873); Stretton (1873); All Saints’ (1898); St. Chad’s (1903); and Shobnall (1916). Holy Trinity and St. Modwen’s were united in 1969, as the parish of Burton-on-Trent, and in 1982 Christ Church and All Saints’ were united.

Despite the division of the parish, St. Modwen’s vestry continued to collect a single church rate for all the town churches. Compulsory church rates were abolished by an Act of 1868, and thereafter a voluntary rate was levied by St. Modwen’s vestry for St. Modwen’s, Christ Church, and Holy Trinity, with the addition of St. Paul’s from 1876. The system was changed in 1879 so that the churchwardens of each of those parishes collected their own rate from individuals, whilst the wardens of St. Modwen’s, on behalf of all four churches, continued to collect the rate from brewers and other firms in the town. Often known as the brewers’ rate, it raised over £411 in 1890, (but thereafter income began to decline as firms withdrew from the scheme and only a little over £209 was given in 1928. Bass, Ratcliff, and Gretton withdrew from the scheme that year to make individual contributions directly to each of the four churches, but St. Modwen’s continued to collect donations from other firms until at least 1954, when less than £23 was given in total.

Church Life from the Nineteenth Century

Services in 1829 were held on Sunday mornings and afternoons, with prayers on Wednesdays, Fridays, and saints’ days and the Boylston lecture on Thursdays. Communion was celebrated eight times a year, with about 70 attending at each occasion. The average Sunday attendance in 1851 was 400 at both morning and afternoon services, besides Sunday school children. A Sunday evening service started in 1860 was so well attended by 1892 that there were hardly enough seats. A children’s Sunday service, probably held weekly, began in 1871 but had ceased by 1892; by 1896 a monthly one had been reinstated. There was a harvest festival by 1877. Further liturgical changes were introduced from the late 1880s, and in 1887 the choir, which then numbered 38, was robed and provided with stalls and a vestry in the upper storey of the tower. Coloured stoles and a chalice veil were first used in 1889, when daily morning prayer was also begun. A New Year’s Eve watchnight service was held for the first time in 1892, and in 1895 or 1896 the celebration of communion was increased from two Sundays a month to weekly. A communicants’ guild, established in 1896, was reorganized in 1899 by the vicar, H. B. Freeman, as the Guild of the Ascension, modelled on one at Christ Church, Bath, where Freeman had been curate. It appears to have folded in 1918. In 1910 St. Modwen’s was described as having ‘a good medium service – not too high, and not too low’, a style still followed in the 1990s.

An unlicensed mission room was opened from St. Modwen’s in the mechanics’ institute in Guild Street in 1871. Run by a lay deacon from Lichfield Theological College, it was closed in 1876. A scripture reader was appointed in 1872, and was styled a lay assistant by 1893, when his duties included running weekly cottage meetings. The post was apparently abolished in 1902. A monthly service in what is called Wetmore Hall, a former Primitive Methodist chapel at the north end of Wetmore Road, began in the mid 1980s, after the transfer in 1969 of that area from Stretton ecclesiastical parish to the parish of Burton-on-Trent.

A parochial lending library of some 132 volumes was kept in the clergy vestry in 1829, but was little used. A monthly parish magazine was probably first started in 1872 and certainly existed by 1892; it continued in 2000.

A mothers’ meeting, begun by 1892, and a branch of the Mothers’ Union, in existence by 1899, were amalgamated in 1927. By 1893 there was a team of women district visitors whose duties included relieving the poor with money and medicines and ‘awaken[ing] the higher life of those they visit’; by 1924, however, they were employed mainly in distributing the parish magazine. A girls’ club, in existence by 1920 and known as the Guild of St. Modwen by 1937, was dissolved in 1970, when its membership included adult women.

A Church of England Young Men’s Association which was formed in Burton in 1846 was opened to all protestants in 1856. A Burton branch of the Church of England Young Men’s Society was formed c. 1878, with premises by 1889 in Friars Walk. Renamed the Parish Church Society in 1892, it was dissolved in 1913.

The former premises of Burton grammar school in Friars Walk were acquired in 1877 for use as Sunday schools and church rooms after the Grammar School was relocated to new premises in Bond Street.

Royal Arms

Royal Arms and Monuments Royal arms hung above the altar in 1829, and remained there until 1865. There were apparently two sets of royal arms in the church in 1869: those of Charles I (1625-1649) in the vestry, and those of George I (1714-1727) in the porch. Nothing further is known of the former, but the latter were still in the porch in 1962 but were later stored in the north gallery. A hatchment associated with the Peel family is also stored in the north gallery.

The Royal Arms were replaced in 1865 by coloured glass depicting the Crucifixion, given by the Marquess of Anglesey. At the same date new side chancel windows depicting the Annunciation, the Transfiguration, the Last Supper, and the Resurrection were given by the brewers Michael Thomas Bass and Henry Allsopp.

1865 Re-arrangement

There was a re-arrangement of the church in 1865. The apse was extended and three stained glass windows were installed. The pulpit was moved to one side and choir stalls were set up replacing the pews on either side of the old three-decker.

Lecturn

The fine eagle lecturn shown below standing in the isle, was given to Saint Modwen’s in 1886 in memory of Alderman John Yeomans.

Altar and Reredos

An Altar and Reredos (decorative screen behind the alter) was added in 1739 which required that the central east window be shortened. It was described after installation as “a beautiful altar piece of Italian marble“. It was gifted by Thomas Hixon, the manorial bailiff, who owned Sinai Park. He left £120 in his will for the purpose. It originally displayed the text of the Ten Commandments, The Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer.

A new communion table was installed in 1879.

Alabaster panels were added in 1889. These show Christ in Majesty in the centre. Also depicted are Saint Chad, Saint Peter, Saint Martha and, of course, Saint Modwen, offering their churches to the Lord. At the same time that the alabaster panels were added to the reredos in 1889, the sanctuary ceiling above it was cleverly painted to look like a mosaic.

In 1870 the congregation was allowed to elect a vicar by secret ballot. Shortly after appointment of the new vicar in 1870, the lecture was moved to Wednesday evening because attendance rarely reached twenty, and most of them were comprised of a group of old women from the almshouses. Again held on a Thursday morning from 1933, the weekly lecture was replaced in 1968 by one given four times a year and the annual payment was directed towards cleaning the church. By a Scheme of 1978 the trusteeship of Boylston’s charity was transferred to the vicar and churchwardens of St. Modwen’s, and the lecture ceased to be delivered c. 1982.

In 1884 the advowson was purchased from the Marquess of Anglesey by public subscription and vested in the bishop of Lichfield. Under the terms of the union of the benefices in 1982 the presentation was to be exercised jointly by the bishop of Lichfield and Lord Burton who were both patrons.

William Tate designed the brass altar cross given in 1889 as well as the candlesticks and processional cross given in 1895. At the end of each arm of the processional cross, seen below, are the Emblems of Evangelists.

In 1883 the three-decker pulpit was split in two: the pulpit was moved to the north-east end of the nave and the reading desk to the south-east end. Carved panels were added to the pulpit by Lord Burton in 1890. A new lectern was acquired in 1886. In 1887 stalls were made for the clergy and choir. In 1889-90 William Tate of London directed the redecoration of the whole interior of the church and the re-ordering of the sanctuary, including a mosaic ceiling in the apse and fluting to the apse pilasters. New furnishings included an oak altar and a brass altar cross; a reredos in alabaster and green marble, with carved panels showing Christ in glory flanked by various saints including St. Modwen, was given by the vicar, C. F. Thornewill, and his two brothers.

Despite its recent improvements, St. Modwen’s was described in the 1890s as “lonely and practically lamented“, lacking the patronage of the brewers that many of the newer churches in the town had attracted. In 1894, however, work began on restoring the church, including the removal of the font from the centre aisle to the south-west corner of the nave; much of the cost was defrayed by the brewers of the town. The architect, J. A. Chatwin of Birmingham, had proposed creating new vestries to replace the choir vestry on the first floor of the tower and the clergy vestry in the south porch, but the expense and local opposition meant that it was not until 1902 that new vestries were added, under the direction of Henry Beck, wrapping around the apse, and again paid for with brewers’ money. By 1904 the brewing families had given £13,000 for the restorations.

Vestries were added around the east end of the church in 1904. This resulted in the shortening of the remaining two apse windows and their glass was moved to the north and south aisles. At some time all the doors were removed from the pews, except for the wardens’ pews at the very back of the church.

A memorial to the dead of the First World War, in the form of a carved oak tympanum with bronze panels, made by Martyn & Company of Cheltenham, was erected in the west porch in 1920. It was extended in 1948 to a design by R. S. Litherland of Burton, as a memorial to the dead of the Second World War.

A Lady Chapel was created in 1956 at the east end of the south aisle.

In 1961 the decoration of the sanctuary was restored by Campbell Smith & Co. of London.

A sepulchral slab inscribed with a floriated cross, and dating possibly from the 14th century, was moved in 1968 from the south wall of the churchyard into the south porch.

Generally, the church has been altered little since it was completed and preserves nearly all its Georgian woodwork and is still a well used church in the centre of Burton.

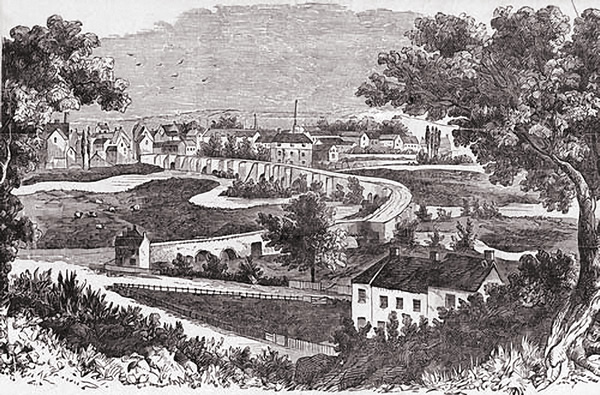

Burton from the East – 1800 (One of the most useful sources of the old bridge)

Burton from the East – 1800 (One of the most useful sources of the old bridge) Trent Bridge at Burton – a scene from the early 1800s

Trent Bridge at Burton – a scene from the early 1800s Burton Abbey – 1812, View of Manor House (Formerly the private residence of the Abbot.)

Burton Abbey – 1812, View of Manor House (Formerly the private residence of the Abbot.) Burton Abbey Gates – 1830 (now Abbey Arcade, High Street)

Burton Abbey Gates – 1830 (now Abbey Arcade, High Street) Peel Mill – 1830s (Still evident as apartments, Newton Road, Winshill)

Peel Mill – 1830s (Still evident as apartments, Newton Road, Winshill) Old Trent Bridge – 1840, although anonymous, this picture provides terrific insight of the time

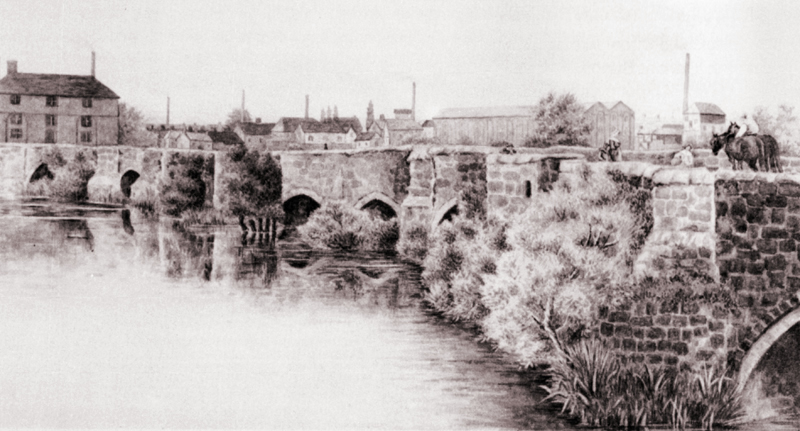

Old Trent Bridge – 1840, although anonymous, this picture provides terrific insight of the time Old Trent Bridge – 1844 by John Harden (Winshill end of old bridge)

Old Trent Bridge – 1844 by John Harden (Winshill end of old bridge) Old Trent Bridge – 1857 by William Wilde (North side, note footbridge and lock gate)

Old Trent Bridge – 1857 by William Wilde (North side, note footbridge and lock gate) View from Stapenhill- c1870

View from Stapenhill- c1870 The Triangle, Stapenhill – by John Harden (Saint Peter’s Street)

The Triangle, Stapenhill – by John Harden (Saint Peter’s Street) Stapenhill Village – by John Harden (Junction of Hill Street and Main Street)

Stapenhill Village – by John Harden (Junction of Hill Street and Main Street) Stapenhill Green – by John Harden (Tree felling on what is now Saint Peter’s Island)

Stapenhill Green – by John Harden (Tree felling on what is now Saint Peter’s Island) Burton Washlands – 1881 (View from top of the new Saint Peter’s Church tower)

Burton Washlands – 1881 (View from top of the new Saint Peter’s Church tower) River Trent – 1890s (View from Stapenhill Road)

River Trent – 1890s (View from Stapenhill Road)

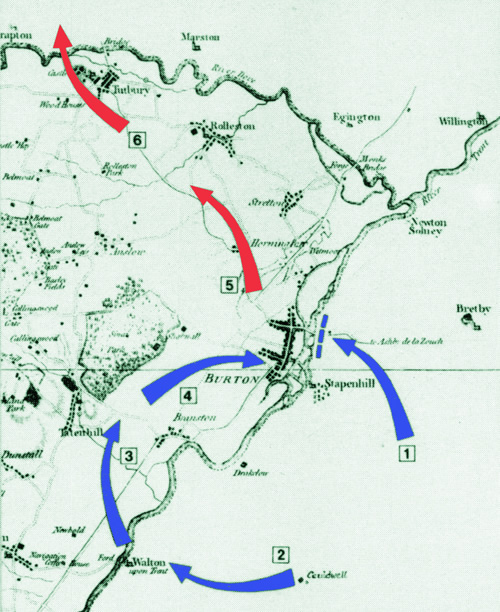

In retaliation, King Edward II (pictured) decided that he would lead an attack against Tutbury Castle and assembled an army in London.

In retaliation, King Edward II (pictured) decided that he would lead an attack against Tutbury Castle and assembled an army in London.