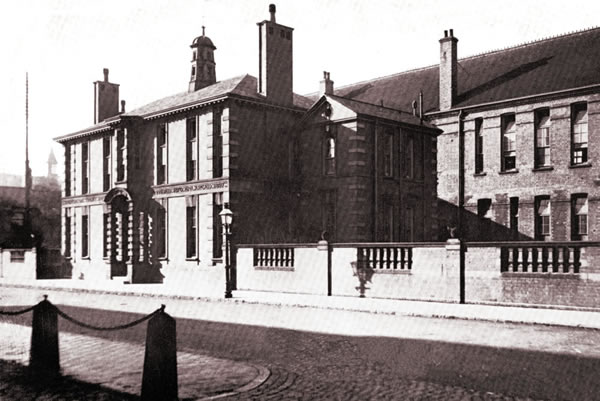

First Burton Hospital – Duke Street

On the 20th March, 1867, a meeting was held in Bank House in the High Street to consider the building of an Infirmary in Burton upon Trent. One curious feature of the occasion was that all seven who came were associated with the brewing trade and no member of the medical profession was in attendance. Possibly the problem was thought at this stage to be a purely business affair, although it is more than likely that at least some discussion with the senior doctors had gone on behind the scenes. Robert Belcher, Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, was brother-in-law to W. H. Worthington, one of the founder members of the committee. It may be the idea had been simmering in the minds of a few people for some time, but the precipitating factor was a legacy of some £450 left by a Mr. Brough of Winshill for the specific purpose of founding a hospital in the town. Whatever other local conditions brought the hospital venture to a head at this time it is extremely doubtful if any member of that committee was aware of just how propitious their timing was. During the previous decade two events had occurred which were to revolutionise the whole future character of the voluntary hospitals throughout the country.

Once the decision to build the Infirmary had been taken the first problem was money. The original concept was to build a twelve bedded unit at an estimated cost of some £1,700. At the first meeting in March of 1867 Major Gretton of Bass’s and Captain Townshend of Allsopps promised a sum of £500 from their respective breweries on the understanding that a further £1,000 would be raised from other sources. It was a method the brewers were to repeat on more than one occasion over the years. Their gifts did not become valid until the whole capital sum for any project had been raised. The town and district was divided between members of the committee to canvas their friends and business associates. Subscription lists were published in the local press giving the names of the donors and the amounts subscribed. It was a method which took full advantage of the principle of keeping up with the Joneses. The slightest hint at an afternoon tea party that the hostess’s name had not appeared on the list caused many a husband to subscribe twice as much as he had originally intended to do. Within a few months over £2,000 had been promised; but promises were not cash in the bank and it is surprising how many subscribers had to be nudged and nudged again before their cheques arrived. By March, 1868, the promises amounted to £2,683 of which only £605 had been actually paid into the Infirmary’s account at the Burton, Uttoxeter, and Ashbourne bank. On the whole the promises were eventually kept and by the time the new Infirmary was opened in October, 1869, only a few pounds had to be written off.

The committee’s second problem was to find an appropriate site for the new building and for the first time the ‘medical gentlemen of the town’ were called into consultation and an area in Duke Street approved. Most of the property was on leasehold to several different owners, but the freehold was in the hands of the Marquess of Anglesey and a deputation waited on Mr. Darling, agent to the Marquess. Darling was a man of considerable business ability and had obviously a good deal of freedom in dealing with estate matters, but not unnaturally his only concern was to see that any transaction was carried out in the best interests of the Marquess. At the first meeting he had rather surprisingly agreed that the Marquess would give the freehold of the actual building site to the Infirmary committee and some additional adjoining property which might be needed for future extensions on a ninety-nine year lease at an annual rental of five pounds, provided the Infirmary bought out the sitting leaseholders. On the strength of this agreement the committee went ahead. Leaseholds were bought over and three architects invited to submit plans for the new Infirmary. With the funds promised now well over the £2,000 mark it was felt possible to plan for a twenty-two bedded hospital rather than the twelve of the original scheme. There was to be accommodation for the nurses, domestics and the House Surgeon, a dispensary, an operating room, and in the blunt language of the time a ‘dead house’ or mortuary. The plans were submitted to the Committee and the doctors and Mr. Holmes’ plan accepted on the understanding that the total cost would not exceed £2,300, the building to be completed in seven months, and the architect’s commission agreed at five percent. Tenders for the building were invited and all seemed progressing well when a letter from Darling brought things to an abrupt halt.

Whether Darling had had second thoughts or whether the Anglesey solicitors in London had queried his original agreement is difficult to say. His letter, dated the 2nd April, 1868, makes no reference to the previous agreement and simply states that the Infirmary committee could have all the property they had asked for on a ninety-nine year lease at a rental of twenty-five pounds a year and he would recommend the Marquess to give an annual subscription to the Infirmary of twenty pounds. The committee was furious. The chairman, James Finlay, adjourned the meeting for an hour or two while he and three others went hot-foot to Darling’s office to protest at what they considered a breach of faith. Darling gave way and agreed to instruct the Anglesey solicitors in London to prepare the deeds on the original agreement, but in the circumstances the promised subscription of twenty pounds a year by the Marquess would be withdrawn. It seemed a little mean, but the committee was satisfied and instructed the architect ‘that the contractors might at once take possession of the land and push on with the building as rapidly as possible’.

The committee’s problems with the Marquess, however, were not yet over. Very rightly they had invited him to be the first President of the new Infirmary, an offer which he had accepted, and when it was decided to hold an official ceremony to lay the foundation stone he was invited through Mr Darling to make his first official appearance on a date to suit his convenience. The ceremony was fixed for the Whit Monday of 1868. The enthusiasm of the members of the committee for the new Infirmary was not altogether shared by everyone in the area. There had been a curious apathy in the town right from the start. When two members of the committee had waited on Lord Chesterfield at Bretby Hall and invited his financial and personal help he had turned them away empty handed. As the descendant of Lord Chesterfield whose ‘Letters to his Son’ is now an English classic, the noble Lord may have had too much of the eighteenth-century aristocrat in him to wish to consort with a malting of brewers, but he was by no means alone in his opposition. As Whit Monday approached the committee became more and more concerned and finally at a meeting convened on the 26th May the secretary had to record ‘there seemed to be some little difficulty in obtaining the attendance of a sufficient number of the committee and other influential residents in the town to meet the Marquess if he came to lay the foundation stone, and it would be better under the circumstances to dispense with any public ceremony at the laying of the foundation stone, but to ask Mr. Finlay, the chairman, to arrange, if possible, with the Marquess to defer his promised visit until the building is finished and ready to be opened’.

There was nothing for it but for the unfortunate Mr. Finlay to travel post-haste to wait on the Marquess at his London residence and explain as best he could that no-one in Burton really cared whether he laid the foundation stone or not. Whether Finlay had the temerity to add insult to injury by inviting the Marquess to open the Infirmary when completed as the committee had suggested is not known. What the first Marquess, who had seen the French off at Waterloo and lost his leg in the doing of it, would have said might well be imagined. What the third Marquess replied is not recorded, but when in October, 1869, the Infirmary was duly opened there were no fanfares, no civic receptions, and no Marquess; the Infirmary simply opened its doors.

There was trouble from a new and unexpected quarter. The whole concept of the Infirmary had been triggered off by Brough’s legacy of £450. Brough himself, of course, had died, but his brother, acting as his trustee, was keeping a watchful eye on what was going on and not liking what he saw. He demanded a meeting, it might well have been called a confrontation, with the committee in February, 1869, and made his view abundantly clear. His brother’s idea apparently had not been the acute hospital the committee was in process of building, but an Infirmary rather in the style of the monks of the old Abbey to look after the chronic and elderly sick. In the second place he affirmed the Duke Street site was no place to build a hospital and in any case the hospital planned was too small to be of any use to the community. Finally when the committee had laid down the specific areas of the town and district from which it would accept patients it had completely omitted the mining villages of South Derbyshire.

It was a difficult situation. The committee had no desire to lose the Brough legacy on a technicality but its own financial position was now strong enough both to stand firm and to compromise. Brough’s first suggestion could not possibly be accepted. The committee had just laid down in its rules that the chronic sick and incurable could not be admitted. Nor could there be any reconsideration of the Duke Street site; the contractors were already in possession. Brough’s last two points were reasonable and could be accepted. The committee had already decided almost to double the accommodation from twelve to twenty-two beds, which in turn made it impossible to increase the catchment area to include the South Derbyshire villages. Brough was somewhat mollified but not very trusting. He demanded not only that the new agreement be put in writing but also published in the local press so there could be no question of the committee reneging; and just to make assurance doubly sure he agreed to hand over a cheque for only half the amount ‘less legacy duty, say £225’, the remaining half to be paid when he was satisfied the Infirmary was large enough to provide accommodation for the people of South Derbyshire. Rather regrettably Brough leaves the story at this point. He must have been an interesting character and few trustees would have struggled quite so hard to have his brother’s wishes fulfilled. The Scots would have called him a bonny fighter and the people of South Derbyshire are still somewhat in his debt.

Over the two and half years the Infirmary took to complete the original committee had added to its numbers, elected a President, Vice-Presidents and trustees, but the major preliminary work had been done almost entirely by the original seven who formed a kind of caucus on which the full committee was based, and in the first annual report in 1870 the number of members was fixed at twenty. No voluntary scheme of this kind could possibly have succeeded without the moral and financial support of the brewers and the names are all there: the Allsopps and the Basses, the Worthingtons and the Grettons, the Eversheds, the Salts and the Nunneleys. A more influential body of men could hardly have been gathered together in any provincial town in England to guide the new hospital through its formative years. Of the twenty members of the committee in the early seventies no less than four were sitting members of Parliament at the same time; two of whom, Arthur Michael Bass and Samuel Charles Allsopp, were to be raised to the Peerage within a few years. From the surrounding countryside the Hardys of Dunstall and the Moseleys of Rolleston were raronets; and over all as President ‘the most noble the Marquess of Anglesey’.

The Marquess was appointed the first president.