The last years of the nineteenth century were to see radical changes in every aspect of the Infirmary’s development. That these changes all occurred about the same time was probably quite fortuitous, but coming as they did in the dying years of the Victorian era it seemed as though all concerned were determined that the Infirmary and all its work would advance into the new Edwardian age in perfect order.

The original Duke Street building was over twenty years old and although additions had been made from time to time, they had been more of a patchwork than a redevelopment. In 1893, the surgeons reported that the floors in the large surgical ward and the operating room were in an unsanitary condition. New floors were laid at a cost of £104. It was reported: “The new floors are of the best English oak and care has been taken to make the joints so tight that no germs can be harboured therein”. The committee’s views on bacteriology may have been rather naive, but it was certainly a compliment to the hospital carpenter. By 1894 it became obvious that something more radical was required and an extension fund was opened which eventually reached the sum of over £20,000 which was a considerable sum.

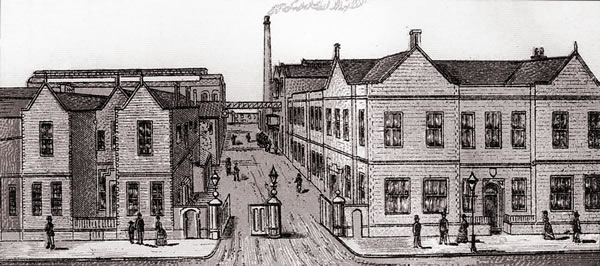

Duke Street

Duke Street

It was probably Lord Burton who was responsible for the choice of architect. Living in Burton as he did (he had a town house in the High Street as well as the Rangemore estate) his enormous wealth and social standing gave him almost autocratic powers quite beyond anything conceivable today and it would not seem in the slightest degree incongruous to him to call in one of the leading architects in the country to pull down and rebuild the small Infirmary in Burton upon Trent. Nor would it occur to Aston Webb, later to be knighted for his services to architecture, and at the time occupied with designing the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington and later the University of Birmingham, to refer Lord Burton to a local builder. Aston Webb came to Burton, assessed the situation, and produced his plan.

Any architect concerned with hospital building in the late nineteenth century had to tread very warily indeed. There was one person of very considerable power who knew more about the design and building of a hospital than the surgeons and architects put together. Long before her time in the Crimea, and even more so after it, Florence Nightingale had been collecting volumes of data on every aspect of hospital work, from the structure of the building itself down to the most minute details of plumbing and kitchen equipment. Her experience in the unworkable hospitals in the Crimea had not enamoured her towards those responsible for building them and on her return to England she was fully determined that things would change. At first involved with the Army Medical Service her association with civil hospitals followed almost automatically. She was just too late to stop the rather panic building by the War Department of the New Military Hospital at Netley. Some £70,000 had been spent on this rather magnificent piece of architecture before she saw the plan and deemed it unworkable; but not even her personal friendship with Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister, could make the Government scrap £70,000 with the considerable loss of face such an act would entail. The finished hospital confirmed her worst forebodings. A magnificent sight from across Southampton Water, within its walls it reduced the nurse’s working capacity by half as she engaged in a perpetual marathon walk along its miles of corridor. It was to be a hundred years before her advice was taken and Netley eventually pulled down.

She had better fortune with the new St. Thomas’ hospital on the south bank of the Thames which was to open in 1870. The woman who opened her ‘Notes on Nursing’ with the words, ‘it may seem a strange principle to enunciate as the very first requirement in a hospital that it should do the sick no harm’, would have been the first to acknowledge with everyone else that a hospital’s purpose was the welfare of the patient. What she altered were the priorities. Her view that the well-being of the patient depended mainly on nursing care, which was certainly true at that time, made the first priority in hospital design not the patient but the nurse. Only by making her working conditions the primary consideration could the hospital succeed. Work study is by no means a modern conception. So detailed was her knowledge of every facet of hospital life that she would have a water tap moved two yards to save the nurse that number of steps. For the first time residential accommodation for the nurse was properly designed and made available for the Nurse Training School in the new St. Thomas’s hospital.

Her second concept, quite radical in its time, but no more than common-sense would dictate, was the building of any large hospital on the pavilion system. With sepsis the great bug-bear of the time it seemed reasonable to design a hospital as a series of self-contained but completely separate units which enabled spreading infection to be at least contained and not run rampant throughout the whole hospital. The system at St. Thomas’s was to have another value in another war which she could scarcely have foreseen. The bombs which were to fall on London seventy years later destroyed two of the units, leaving the rest to carry on undisurbed.

The architects had to conform if for no other reason that her standing in the country and with the Government itself was such that no committee concerned with building a hospital of any size in any part of the country would have a stone laid without her opinions on the plans and her opinions could be vitriolic.

Although Florence Nightingale played no part in the new Burton Infirmary there can be little doubt that Aston Webb knew all about Netley and St. Thomas’s, and although Burton was a small unit it was built on the Nightingale lines. The days of special departments were a long way ahead. Wards were medical or surgical and the design of a ward in any hospital built between 1870 and 1900, whether in a teaching hospital in London or a small Infirmary at Burton, was exactly the same.

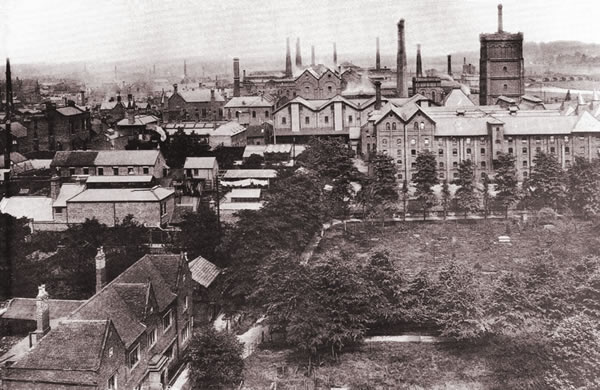

New Street

New Street

The new hospital was completed in 1899 with a complement of seventy-two beds which was a much larger increase in capacity than the figures imply since Typhoid Fever and Diphtheria, formerly such a problem to the staff, were now admitted to the new Isolation hospital and the Infirmary ceased to admit fevers of any kind. Inevitably within a few years the hospital was too small for the increasing number of patients and over the years became a kind of architectural hotch potch, with so many additions, subtractions and divisions that by 1930 Aston Webb’s original design had become almost unrecognisable.

When opened in 1899, however, it was a small compact hospital of no great architectural merit, but not unpleasing to the eye (Aston Webb would never have built anything shoddy) and within its compass contained every modern development of the time. It was built in three separate units. A two storey block with a central doorway was laid out on the Duke Street front. On the ground floor the Matron’s quarters and Board Room were on the left of the entrance, with a fairly commodious flat for the still single House Surgeon on the right. Above these quarters was the single Ratcliff ward named after the Misses Ratcliff of the brewing family who had offered to defray the cost of one complete ward as their contribution to the new hospital and eventually paid for the whole block.

From the entrance a corridor ran the whole length of the property from Duke Street to New Street. The main unit of four wards was set back from the entrance block in parallel with it, while a new Casualty, Out-Patient Department and Dispensary were built on the New Street front where the main entrance to the hospital was sited, with nurses’ and domestic servants’ accommodation above.

Apart from some variations in size each ward was of identical construction. Rectangular in shape with long windows down either side and beds between, the ceilings were high, allowing the requisite cubic feet of air space per patient while keeping the floor area to a workable size. Piped water, which had been an innovation in the eighteen-sixties when even the largest private houses had no more than a single tap laid on to the ground floor, was now available throughout the hospital, but only to the ward kitchens and sluice rooms. In the ward itself the huge flat-topped cabinet in the centre always held in pride of place a basin and ewer with a small hand towel neatly folded. Filled with warm water by a junior probationer, for the surgeon on completing his ward round, it became a kind of ritual procedure for sister to fill the basin and stand ready to hand the chief his towel.

While piped water throughout the hospital was standard, central heating was a completely new innovation but, with some doubts as to its efficiency, the open coal fire was still a standard feature of every hospital ward. Built in the form of a cube about five feet high and faced with green tiles these were sited in the centre of each ward with an open coal fire on two sides. Unlike the American stove with its central chimney the flues were carried under the floor, in itself a form of central heating as old as the Romans, to emerge in a buttress-like chimney stack on the outside wall. No doubt they were somewhat dirty and repeated filling of the scuttles an unwelcome chore for the porters, but they gave a feeling of warmth and welcome to the visitor which no later form of heating has ever replaced, and never again will the patient have the comfort of dozing off with the firelight flickering on the walls and the night nurse in her chair before the fire, able at the turn of her head to see all that was going on.

At the far end of the ward the sluices and toilets were built out in a three-sided annexe which by its three windows gave maximum ventilation where it was most needed at a time when ventilation depended entirely on windows and flues. At the ward entrance the kitchen, serving also as sister’s room was fitted with the kitchen range, complete with open fire and side oven, where for many years breakfast and tea for the patient were prepared by the nursing staff. A small window opening from the kitchen to the ward still enabled sister, having a quiet cup of tea, to command a view of all her patients, and what was sometimes more important, keep an eye on her junior staff.

The building of the new Infirmary was not without its prohlems. Once the decision was taken at a meeting in the board room of Bass’s office under the chairmanship of Lord Burton, and Aston Webb called in for preliminary talks, a building Committee consisting of four members of the main committee and Philip Mason the surgeon had been elected in May, 189fi, to look after the hospital’s interests. It was a matter the members took very seriously. They were prepared to pay for the best materials and equipment and while the building contract had been given to the local firm of Lowe’s, on Aston Webb’s advice leading firms from London were called in to deal with their various specialities. Any flaw or defect detected by the Building Committee had to be put right and the members kept a very careful check through every stage of the new development. For over three years until final completion in 1899 the committee met almost monthly and more often than not Aston Webb was in attendance, brought down from London to deal with every problem as it arose, He had probably sensed something of the situaton and assessed the type of committee with which he was dealing, when in his original agreement with Lord Burton and the main committee he had accepted a fee of live per cent on the building costs but wisely inserted a clause that the committee would be responsible for his railway journeys to and from London; over the years they were not a few.

The innovation of installing ‘the electric light’ had been taken with some trepidation, and a few gas jets had been left at strategic points throughout the building in case of emergencies. For a few months there were problems. Bulbs grew dim and flickered out; fuses blew and left the ward in darkness; newly-plastered walls had to be reguttered for new wires; and Verity & Company of London, who had installed the equipment, had to pay a few extra visits at their own expense. The central heating brought its own problems. The pipe from the boiler was too small and the number of radiators required to heat the high ceiling wards had been under-estimated. But while the patients at the far end of the ward had to have extra blankets and hot water bottles, at the near end where the ward wall adjoined the kitchen they were perspiring from another cause. The kitchen ranges with open coal fires had been fixed against the adjoining wall and with coal at eleven shillings a ton causing little need for economy, the fire roaring day and night made the wall almost too hot to touch. All the ranges had to be brought out four-and-a-half inches and an extra layer of brick work put in to absorb the heat.

The operating unit had been fitted out by Aston Webb but the new operating table had been the personal responsibility of Walter Lowe and Philip Mason who had purchased it in London, and on its breaking down were duly asked by the committee to have it repaired and ‘find out how the accident had happened’. Some of the expressions used in connection with this unit sound rather strange today. The word ‘theatre’ did not come into use for some years. It was still just the operating room and what is now the anaesthetic room was referred to as the preparation room. It takes a moment or two’s reflection to appreciate that the ‘lavatory basins’ installed in the operating room were in fact the surgeons’ wash basins, the word still being used in the true meaning of its Latin derivation; and the modern anaesthetist might be interested to know that the ‘vomiting sink’ in the preparation room was no longer considered necessary. One somewhat startling expression occurs during the discussion on the size of the doors opening into the preparation and operation rooms ‘in reference to the facility for getting the ambulances in and out of these rooms’. Why a word originally meaning to walk should have come to mean to carry is a problem for the etymologists, but the expression, with only one connotation at the present day, was used by the Victorian surgeons to denote any conveyance on which a patient could be carried in this case the trolley on which he was brought to and from the ward.

Another advance in development was the first installation of a lift to avoid carrying patients up and down the stairs on canvas stretchers but it proved to be no quicker. Matron timed it to take three minutes to rise from the ground to the first door and Aston Webb’s enquiries of the makers brought the explanation that it was manually operated by one man winding it up and down and that it was impossible to do it any faster. Electric power had not yet been extended to lifts.

Some of the complaints were rather puerile in the true sense of the word. Matron complained that small boys were climbing on to the window ledge of her new sitting-room which faced directly on to Duke Street and upsetting her privacy. After some discussion it was gravely decided ‘to take no action at the moment thinking that when the novelty wore off the annoyance would cease. Small boys appear to have been the source of some concern in the committee on various occasions. A new boundary wall in Duke Street had to be topped by iron spikes to prevent their walking along it; and it was not long before attention was drawn to the habit of boys slipping into the new Out-Patient Department in New Street to utilise the toilets provided there for the patients. The cure of this problem by increased staff supervision merely produced a worse one. The little boys used the entrance porch Instead. By the end of 1899 most of the teething problems had been overcome.

New furniture (from Maples of London) had been installed, the board room lilted out at a cost of over £100. This even included a piano for the wards. It had taken some four years to complete, but the committee could fairly congratulate themselves in having produced a hospital which though small in size could compare with the best in standards and equipment. Aston Webb had done litem well, but was no doubt happy to see the end of the Buildings Committee as the new century began.

Over the years the nursing staff had increased in size and Miss Ransford, who had been Matron since 1888, resigned in 1900. She had dealt with the Typhoid epidemic of 1892 and had been mainly responsible for the eventual cessation of the admission of infectious fevers to the hospital altogether. In spite of all the troubles and turmoil of the rebuilding programme she had increased her staff and continued the training school.

When it had been decided in 1885 to discontinue the association with Derby and train its own staff in Burton, the committee had asked Miss Ransford’s predecessor, Miss Browne, the last of the Lady Superintendents, to draw up a report on the nursing situation. It was her opinion that the Infirmary, with some sixty beds, dealing with just over three hundred In-Patients and nearly six hundred Out-Patients, could be adequately nursed by herself at £80, three nurses at £18 to £25, and three probationers at £8 a year. It was little enough to start a training school, but there was nothing to stop any hospital doing so; no Nursing Council, no State Registration, nothing but the arbitrary rules laid down by Florence Nightingale Thomas’s Hospital in 1860, and more or less copied by Miss Browne at Burton.

– Young women of suitable age and good character will be received into the Infirmary to be trained as nurses at wages of £8 a year.

– They will also be taken for training on giving their services without pay or, in special cases of payment of £1 a week.

– The course of training extends over a period of twelve months, during which time the pupils are required to act as assistant nurses and are subject to all rules connected with the Infirmary.

– One month’s trial is allowed and if at the expiration of that time the Matron reports the pupil suitable to follow the occupation of a nurse she will sign an agreement binding herself for one year.

– No distinction will be made in any way for probationers in the Infirmary whether they pay for their training or are paid by the committee; or give their services…

– All nurses and probationers have to sign an agreement binding them for one year.

Uniforms to be provided :

One heavy dress – £0 14s 6d

Three linen dresses – £1 0s 0d

Six aprons – £0 8s 0d

‘One heavy dress every year and the linen dresses and aprons every two years.’

The acceptance of unpaid probationers and more particularly of those who actually paid for their training was a dangerous step which no doubt Florence Nightingale had taken with her eyes open. It was crucial to the success of the nursing service she was trying to develop that it must attract women of some education which at that time could only mean women of a higher social class – a class to which she herself belonged and of whose foibles she was well aware. For this type of woman to accept a salary in the eighteen-eighties was to put her on a par with a paid governess, to reduce her social status, and almost ostracise her from her own kind. The Lady Probationer was an initial necessity to attract the educated woman to the new service; she was unpaid and was giving a charitable service, and if she paid for her tuition it was no different from paying the music master to teach her the pianoforte. Florence Nightingale knew how to deal with the snobbery of her time and also the inevitable effect of her decision. It split the nursing service right down the middle. The Infirmary rules might say there would be no difference in any way in the treatment or training, but the salaried probationer knew better. Quarrels and jealousies arose. The paid probationer felt the Lady Probationers were better treated and more favoured for promotion; and the latter suggestion at least was not without reason.

Lady Probationers received quicker promotion, not because they were ladies but because being ladies they were more highly educated. Necessary as the Lady Probationer was in the early years, as the service developed the situation became as untenable as the position of the Lady Superintendent, and Miss Ransford, the first of the new Matrons, had stopped it altogether. From the nineties onwards all probationers were paid their salary of £8 a year, and shortly afterwards the legal agreement signed by the nurse binding her to a year’s service, was also cancelled.

The Matron held supreme pride of place in an institution run on almost convent lines. The surgeons no doubt appeared daily and although received with some deference were visitors from an outside world. The Secretary was a member of committee and acted in a purely honorary capacity and when he or the chairman paid their calls they were received by Matron in her sitting room where the problems of the day were discussed and Matron’s views given very serious consideration. Within the hospital walls it was a female society. Even when departments developed outside the province of pure nursing Matron still remained in control. The cooks in the kitchens came under the charge not of the chef but the kitchen sister. The living-in domestic staff, and of course the nurses, came under Home sister’s rule; even when the X-ray Department came into being some years later the radiographers were trained nurses and all directly responsible to Matron. This closed community of unmarried women was made closer still by the fact that few of them were local girls with families or relatives in the town. It was considered wrong, and probably rightly so, for a nurse trained in the hospital to be promoted to Sister without widening her experience for a year or two in another hospital and many in fact did not return. Most of the Sisters, therefore, came from other hospitals and other towns. It was even considered unwise to admit local girls for training and every attempt was made to recruit them from elsewhere, even as far away as Ireland, on the grounds that local girls might be too ready by accident or design to gossip at home about the hospital or its patients. The privacy of the patient was sacrosanct, not only to the surgeon but to the nurse. For many years the age of a private patient was not allowed to be recorded on his notes or temperature chart. The appointment of a Matron was a matter of great importance. She could make or mar the whole hospital. She had autocratic powers but had to use them with tact and discretion. Burton was fortunate.

By 1900 the Infirmary had achieved a position of some standing, mainly through the reputation of Walter Lowe among other Midland surgeons and their hospitals, and when Miss Butler was appointed Matron to the new hospital she was selected from a list of no fewer than ninety-four applicants for the post. The above photo taken at Christmas 1906 provides a good feel for a typical ward when the hospital was new.

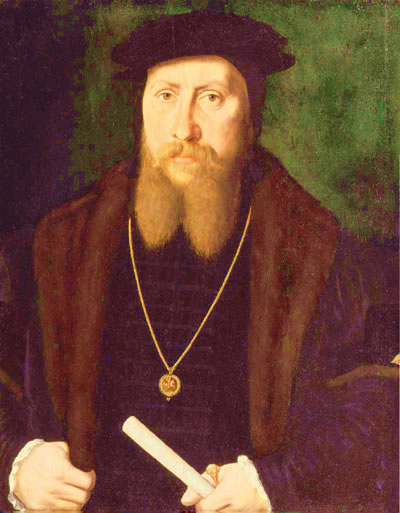

In Tudor times, William Paget was one of the most prominent men in England. Son of John, one of the serjeants-at-mace of the city of London, he was born in London in 1506. His father was said to have been of humble origin from Wednesbury, Staffordshire. Educated at St Paul’s School, and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, proceeding afterwards to the university of Paris.

In Tudor times, William Paget was one of the most prominent men in England. Son of John, one of the serjeants-at-mace of the city of London, he was born in London in 1506. His father was said to have been of humble origin from Wednesbury, Staffordshire. Educated at St Paul’s School, and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, proceeding afterwards to the university of Paris.

Field Marshal Henry William Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey KG, GCB, GCH, PC (17 May 1768 – 29 April 1854), known as Lord Paget from 1784 to 1812 and as the Earl of Uxbridge from 1812 to 1815, was a British military leader and politician, now chiefly remembered for leading the charge of the heavy cavalry against d’Erlon’s column during the Battle of Waterloo. He also served twice as Master-General of the Ordnance and twice as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Field Marshal Henry William Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey KG, GCB, GCH, PC (17 May 1768 – 29 April 1854), known as Lord Paget from 1784 to 1812 and as the Earl of Uxbridge from 1812 to 1815, was a British military leader and politician, now chiefly remembered for leading the charge of the heavy cavalry against d’Erlon’s column during the Battle of Waterloo. He also served twice as Master-General of the Ordnance and twice as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

(known until 1880 by the courtesy title of Lord Paget de Beaudesert and from 1880 until 1898 as Earl of Uxbridge)

(known until 1880 by the courtesy title of Lord Paget de Beaudesert and from 1880 until 1898 as Earl of Uxbridge) In brief, Stanley William Clarke was businessman and racecourse owner. Born in Burton upon Trent from a fairly humble background, he rose to become chairman and president of St Modwen Properties plc and was a founder and chairman of Northern Racing. He was appointed CBE in 1990 and knighted in 2001.

In brief, Stanley William Clarke was businessman and racecourse owner. Born in Burton upon Trent from a fairly humble background, he rose to become chairman and president of St Modwen Properties plc and was a founder and chairman of Northern Racing. He was appointed CBE in 1990 and knighted in 2001. His success allowed him indulge his life long love of horse racing but, unlike most who have to content themselves with buying a racehorse, in 1988 at age 55, he bought Uttoxeter Racecourse! Though the course was struggling at the time, it was quickly transformed under Clarke’s ownership. He gave each of his courses a distinctive green and white livery as part of a re-branding that concentrated on quality.

His success allowed him indulge his life long love of horse racing but, unlike most who have to content themselves with buying a racehorse, in 1988 at age 55, he bought Uttoxeter Racecourse! Though the course was struggling at the time, it was quickly transformed under Clarke’s ownership. He gave each of his courses a distinctive green and white livery as part of a re-branding that concentrated on quality.