Ferry Bridge – Building and Opening

BRIDGE FINALLY AGREED

Reported on an 1886 meeting: “Alderman Evershed and Councillor Chamberlain convened a meeting at Stapenhill to consider improvements to Stapenhill Ferry. The Major, who presided, said the ferry was 100 years out of date and a footbridge was urgently needed. He said that Lord Angelsey had a life interest in the ferry rights and the whole of the estate was in the hands of the trustees. There was a clear income of £560 from the ‘rights’. His proposition ‘that the delay and inconvenience of the present ferry boat, especially on dark and foggy nights, was intolerable and that the meeting approve the desire of the trustees of Lord Anglesey to erect a footbridge, and earnestly support them in taking prompt action to carry out the work’, was carried”.

Hopes were raised when, in 1865, the Marquis of Angelsey obtained an Act of Parliament authorizing him ‘to build and maintain a bridge over the river Trent, near the town of Burton-upon-Trent, at or near the site of Stapenhill ferry, with approaches thereto’. This bridge was originally intended to be a second river crossing that was on par or better than the existing Burton Bridge. Plans for a traffic carrying bridge were drawn up but, much to the dismay and disappointment of the many ferry users, the work never progressed beyond the planning stage. The ferry users were still hopeful that a river crossing would still be built by some other means and it was generally perceived that the Marquis of Angelsey was responsible for the halting of the proceedings.

Almost a decade later, still frustrated, the inhabitants of Stapenhill began a new determined campaign to push their demands for a second bridge to coincide with the local elections. Any candidate seeking election for that ward on the Town Council would not have stood any chance of winning had they not given their whole-hearted support in favour of these fervent calls to be met.

After still more years of inactivity, in 1885 the Marquis of Anglesey applied for new parliamentary approval, but this time, only to erect a much less ambitious footbridge over the river Trent near the site of the Stapenhill ferry and to sell the rights and the ferry to the Burton Corporation. The application was approved in 1886 but the general sentiments were that the sum being asked by the Marquis were much too high.

After considerable time and frustrating negotiations between the council and the Marquis, Sir Michael Arthur Bass (later to become Lord Burton) came forward with a generous offer to build a footbridge at his own expense, as long as the council bought the rights from the Marquis. After still more delays due to further negotiations between the Marquis and the Council over remuneration, terms were eventually agreed upon with the Marquis agreeing to sell the rights for the Ferry and the Bridge for the then substantial sum of £12,950 from the Corporation.

Having acquired the rights, the Corporation agreed to retain the services of the men who had worked the ferry and to arrange for the purchasing of the boats from Mr Darling, the agent of the Marquis of Anglesey.

A letter was received by the Town Council in January 1888 from Messrs. J & W.J. Drewery, stating that the completion of the purchase of the ferry could now be entered upon. The committee recommended that a cheque for £12,950 be forwarded in favour of the bankers of the Marquis of Anglesey’s Trustees and that one of £32 19s 6d balance on account for outstanding tolls. To put this is perspective, ferry toll receipts for the final month were recorded as £67 10s 5d.

Lord Burton finally selected Messrs. Thornewill and Warham Limited, a highly esteemed local engineering company, to erect the bridge and, after design plans and costs had been agreed, work was at last commenced in 1888.

THE BRIDGE BUILDER

THE BRIDGE BUILDER

Thornewill & Warham Engineering Limited was established in Burton during the late 1830s with a partnership between local engineer, Robert Thornewill (pictured) and John Robson Warham, an engineer from South Shields. Its main concern was the manufacture of pumping and winding engines, most for Midland’s collieries.

By 1861, the company had 178 employees and had expanded into manufacturing steam locomotives for the local breweries. By 1870, it had a national reputation for producing steam engines and began to export engines all over the world. It gradually acquired more land to build a large site that extended between New Street and Park Street adding a number of iron foundries. During its continued growth, Thornewill & Warham supplied the majority of all iron-work for the rapidly expanding brewery construction projects.

In 1883,the company was approached to supply a substantial iron bridge to replace the wooden footbridge that linked the main town to Andressy island. The following year, in 1884, the new impressive Andressey Bridge was opened to great success. This made them natural candidates for the construction of a new Ferry Bridge. Not wishing to be cynical, it may also have helped slightly that Lord Burton was married to Robert Thornewill’s daughter.

Whilst the company was enthusiastic to supply the proposed bridge, they didn’t have anyone within the company with sufficient bridge building experience to erect a bridge of such span when it was agreed that the bridge would require some sort of suspension design. Mr Edward William Ives played the main role in designing the bridge. He had been involved with a number of construction projects for Thornewill and Warham, including the Andressey Bridge built a few years earlier. However, he had never designed a bridge of such span and so the services of Mr Langley were sought. Mr Langley was an eminent engineer in the Midland Railway Company. With strong bridge building experience for the railway industry, he took great interest in both the design and construction of the bridge and made his full engineering experience available.

The large factory of Thornewill and Warhams was between New Street and Park Street. In its glory days, it was difficult to imagine such an engineering company ever disappearing. Around forty years after the construction of the Ferry Bridge however, the company had disappeared in the decline of heavy engineering. The site was taken over by S. Briggs and Company in the 1929. The remainder of the assets were acquired by the new ‘Burton Copper and Engineering’ which started in an abandoned brewery in Moor Street. The site was finally vacated when S. Briggs was re-located to Derby Street to make way for the new Octagon Shopping Centre leaving no trace.

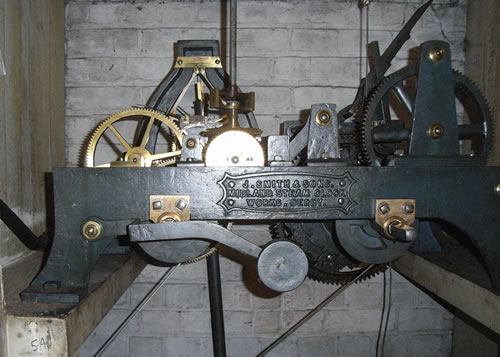

One of a number of plaques to commemorate the builders

One of a number of plaques to commemorate the builders

THE BRIDGE

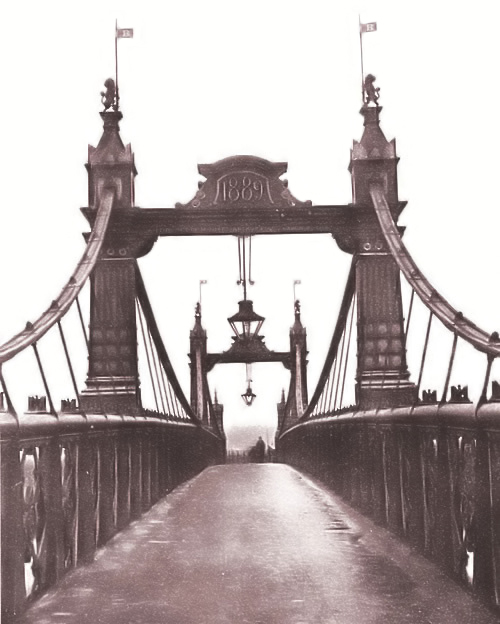

The original work was for the Ferry Bridge itself but did not yet include the causeway. For a few years, there would still be a path across the meadows between the Ferry Bridge and Burton. The Ferry Bridge was 240 feet in length and had a walkway width of ten feet.

The construction of the bridge was on a suspension principle. Its distinctive feature being the chains which are made of flat bar iron, riveted to the ends of the main girders. These chains are continuous from one end to the other and are not anchored at the ends as they would normally would be on a traditional suspension design. This form of construction had not been previously used and was the first bridge in Europe to be constructed in this way.

It spanned the river in three sections, supported by four cast iron piers, five feet in diameter. These were placed in pairs fifteen feet apart from centre to centre. The piers were sunk to a depth from twelve to fifteen feet below the bed of the river to a solid foundation of marl and sandstone. The centre section was 115 feet long with the two symmetric end sections measuring 57 feet. The bridge stood eleven feet above the average water level at the centre and nine feet above the water at each end.

The cylinders were filled with solid concrete and on top of this was built three feet of non-porous engineering blue bricks cemented together. Finally, to complete the foundation, was an ashlar stone bed onto which the towers were erected.

The towers were cased externally with ornamental cast-iron work and stood 23 feet 6 inches high, the bases being panelled and decorated with the arms and supporters of Lord Burton, together with his motto – ‘Basis Virtutum Constantia’ (The basis of virtue is constancy). The towers were surmounted with lions rampant and carried wrought-iron staffs with gilded copper vanes and his monogram. They were indeed a great tribute to the superb Victorian craftsmanship that existed in the Town.

The bridge is 240 feet long and the roadway is 10 feet wide. It crosses the River Trent in three spans, the centre span being 115 feet wide between the piers and the two side spans each being 57 feet wide between the piers and the stone abutments. The height of the underside of the bridge from the average water level is 9 feet at the ends and 11 feet in the middle.

The towers over which the chains pass are carried on four cylindrical piers and are placed in 2 pairs, 15 feet apart from centre to centre, 5 feet in diameter (the diameter of the cylinders was fixed upon as providing the smallest area inside which the men could conveniently work) and are sunk to a depth from 12 to 15 feet below the bed of the river to a solid foundation of marl and sandstone.

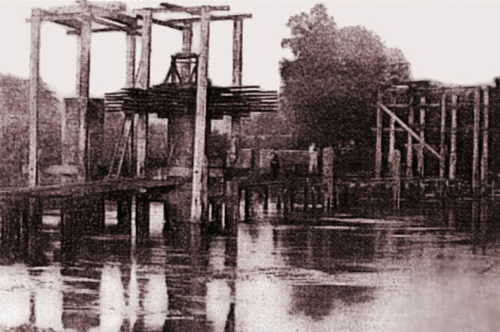

The water was pumped out of the cylinders by a pulseometer supplied with steam by a portable boiler and the earth and rock was hoisted to the surface in a bucket. Large piles were driven at the sides of the cylinders to keep them vertical and to strengthen the overall structure. The cylinders were filled with concrete and upon this is laid 3 feet of blue bricks and a stone bed onto which the towers were erected.

The towers are contracted of wrought-iron lattice work 2′ 3-1/2″ (two feet three and a half inches) at the bottom to 1′ 4-1/2″ (one foot four and a half inches) at the top and 20’3″ high. They are braced together at the top by a lattice girder 11-1/4″ (Eleven and a quarter inches) deep. The towers are cased externally with ornamental cast iron work 23’6″ high, the bases being paneled and decorated with the arms and supporters of Lord Burton and his motto: Basis virtutum constantia. The towers are surmounted with lions rampant (his lordships supporters) carrying wrought-iron staffs with gilded copper veins with his monogram.

The girders are continuous from one end of the bridge to the other. They are 6 feet deep, the top and bottom flanges are made of “T” iron 6″ by 6″ by 1/2″ thick. The lattice bars 3″ by 3/8″ of flat iron and stiffened by double angle irons and gusset plates. The longitudinal girders are tied together by lattice cross girders 12″ deep in the middle and 6″ deep at the ends, and wind ties of flat iron are also placed between these girders. The longitudinal girders formed the parapet of the bridge, the top and bottom flanges being cased with ornamental iron work, and the junction of the lattice bars enriched with ornamental castings.

The chains are made of flat bars 3 inches thick, riveted in the middle of the centre span and at the ends of the bridge to the main girders. The piers and towers are placed outside the main girders, which increases the resistance of the bridge to wind pressure, the distance between the chains being wider at the tower than at the middle and ends of the girders. The chains are simply riveted to the ends of the girders and not anchored to the masonry of the abutments, so that the whole bridge is self contained. The main girders are hung from the chains by suspension rods one and a half inches in diameter. The roadway was originally red deal 3 inches higher in the middle than at the sides to allow run off of rain water.

The bridge was tested by loading the middle section of the bridge with several tons of old rails and its rigidity was further tested by 20 men from the Staffordshire regiment marching at double time across the bridge. This was considered the most severe test that a suspension bridge could be exposed too. The lattice girders which tie the towers together are cased with more ornamental iron work bearing the date of the erection of the bridge, 1889 and underneath this the inscription The gift of Michael Arthur First Baron Burton.

The bridge was lit by two lamps hanging from each of the cross braces between the towers and the heavy cast iron lamp pillars in character with the towers at the ends of the bridge, bearing four more lamps. Lord Burton also diverted the pathway so as it was to make it lead directly to the bridge from the fleetstones and replaced the small wooden bridge over the ditch cut to the silver way with a small lattice girder bridge of similar design to the main bridge.

The total weight of the iron work of the bridge is over 200 tons. The stone abutments were built by Messrs Lowe and Sons, and the carving of the patterns being executed by Mr Hilton of Victoria Street Burton. The total cost of the structure including the diversion of the roadway the iron work approach, the small bridge, the earth work embankments, and the purchase of the land for the improvement of the roadway on the Stapenhill side of the river was between £6000-£7000. Once built the bridge was testament to the quality of the local workforce and the expertise of the contractors concerned.

THE OPENING

In early 1889, Sir Michael Arthur Bass (still not yet Lord Burton) contacted the Mayor and advised him that the bridge would be completed and an official opening day was set for Wednesday 3 April 1889. The bridge was decorated bridge the day before and crowds began to assemble early. From early morning, many people crowded onto the ferryboat to take the opportunity of a trip on the very last day of operation. The weather was wet and stormy which was a big disappointing. Nonetheless, a crowd estimated at between eight and ten thousand assembled on the Burton side of the river alone. Although heavy grey clouds filled the sky, the rain held off, but it was still uncertain as to whether Sir Michael, who had not been too well, would be able to attend the ceremony. Fortunately, these fears were unfounded.

Sir Michael Bass and his party drove from Rangemore Hall to Stapenhill House, residence of C.J. Clay JP. Stapenhill House occupied the upper terrace of what is now Stapenhill Pleasure Gardens and the whole of what is now Stapenhill gardens belonged to the house with a tennis court occupying the place now taken by Burton’s iconic white swan. The party walked down Jerram’s Lane to the Ferry Bridge and word was given to stop the ferry boat at ten minutes to ten in readiness for its one final historic trip which would carry the opening party.

Cheers from the crowd which had reached an estimated 8,000-10,000, rang out as the party crossed the bridge and boarded the ferry boat on the Burton side. Mrs Burton entered first, followed in order by Sir Michael Arthur Bass, Sir W. and Mrs Plowden, Sir Michael’s brother-in-law, the Hon. Miss Bass, the Mayor and Mrs Harrison, Misses Kathleen and Violet Thornewill, the daughters of Mr and Mrs. Thornewill, Mr and Mrs C.J. Clay and Mr G. Burton.

On the front row above are Mrs Harrison, Sir M.A. Bass (later Lord Burton), Nellie Bass (with Misses Kathleen and Violet Thornewill), Mr C. Harrison (Mayor), Mrs Bass.

Safely across, they went up on to the bridge for the formalities. The Mayor presented Mrs Burton with a boatshaped fruit dish in solid silver, its engravings including a representation of the bridge and an appropriate inscription. The work had been carried out by Mr A.J. Wright, jeweller of 170 High Street. Sir Bass was then given an elaborate illuminated address subscribed for by over 5,000 people. Sir W. Plowden MP replied on behalf of Sir Michael who had a throat infection and proceedings were handed over to the Mayor.

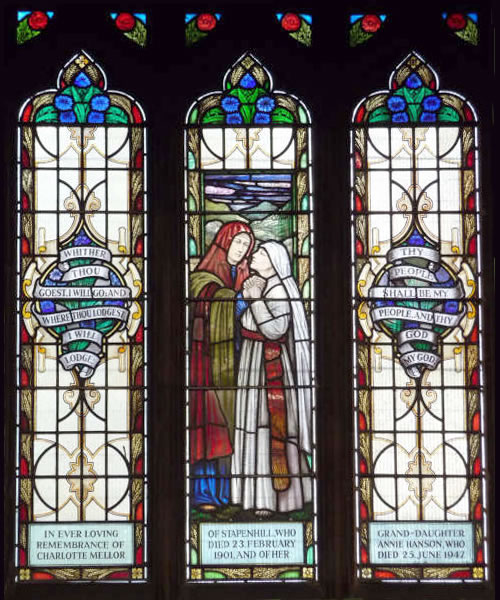

Title deeds in connection with the bridge were officially handed over to pass responsibility of the structure to the Corporation. Following an introductory speech of thanks by Mayor Harrison, Mrs Burton was invited to declare the bridge open. Stepping to one side of the bridge, Mrs Burton, speaking in a clear voice said, “I declare this bridge open, and I hope it will be of great benefit to the public”. The declaration was greeted with much loud cheering and flag and handkerchief waving and in the distance, the bells of both St. Paul’s Church and those of St. Modwen’s rang out.

The official party then adjourned to St Paul’s Institute a substancial banquet with many courses, toasts and long speeches. It was here that Sir Michael Bass announced to the guests his proposal to erect a raised causeway across the meadows to provide a safe crossing from the Ferry Bridge to Burton, avoiding the muddy trek from the Fleetstones bridge across the meadows to the new Ferry Bridge. This generous proposal was welcomed with enthusiasm from those present.

The public cheerfully crossed and re-crossed the bridge free of charge for the day and no doubt drank in local hostelries to the words on a banner draped across The Dingle – ‘Three Cheers For Bass’.

Once the bridge had been opened, it was featured in the ‘Illustrated London News’ – the World’s first illustrated newspaper founded in 1842 by Herbert Ingram who went on to become editor of Punch magazine.

The Illustrated London News enjoyed a country-wide weekly distribution of around 25,000 making it a major publication at the time and helped to put the Ferry Bridge on the map.

EARLY HISTORY

EARLY HISTORY