Station History

Old Station (1839)

Burton’s first railway station was opened in 1839 by the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway on its original route from Derby to Hampton-in-Arden meeting the London and Birmingham Railway for London. The station stood at end of what was then called Cat Street, which was eventually renamed in 1844 to the now much more familiar Station Street.

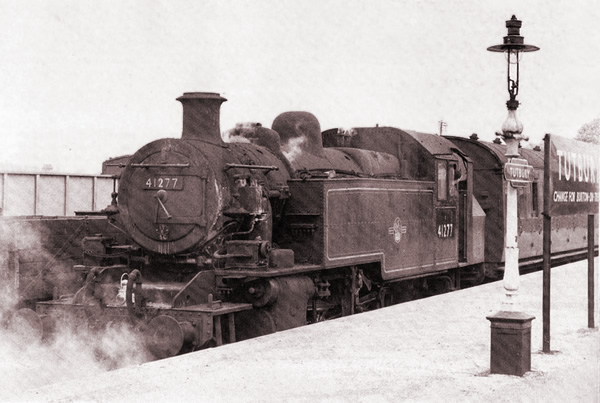

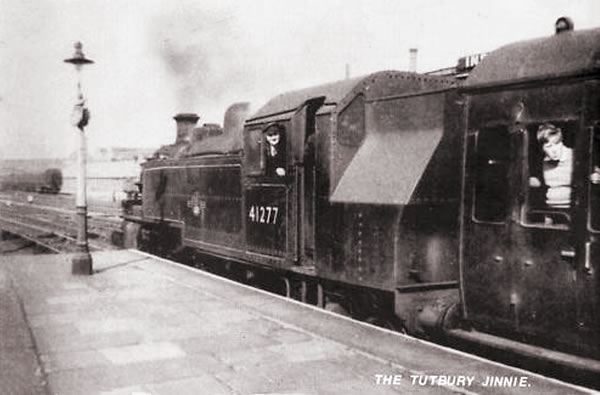

In 1848, the North Staffordshire Railway Company opened a line from Crewe to Derby, with a branch line from Uttoxeter which connected Tutbury and Burton. A small passenger train known affectionately as the Tutbury Jinny, seen below, was a popular sight at the old Burton station. It operated a push-pull service between the two stations.

This later became known as the more colloquial ‘Tutbury Jinnie’ and became important for commuters and shoppers, who travelled from Tutbury to Burton.

In its heydey, the ‘Tutbury Jinnie’ provided eight trains each way on weekdays and two on Sundays. However, as the motor car became more accessible, a survey in 1960 revealed that the service was only carrying an average of twelve passengers and running at a loss of around £7000, which was quite a significant sum at the time. The service managed to survive until it was withdrawn in 1960 when a ceremonious packed last train left Tutbury at 8:12pm on 11th June.

It can be seen above and below in its more ‘modern’ guise in its final years.

Tutbury station was fully closed in 1966 but was re-opened by popular request in 1990 and remains in use today.

A year after the previous line, in 1849, the Midland Railway Company, which now owned and operated the Birmingham to Derby line, opened a line from Burton to Leicester which crossed the Trent by a substancial viaduct still known today as the Leicester Line Bridge.

Burton’s main streets became congested by drays delivering barrels to the station from the breweries which were mostly located near the river. As early as 1853 it was proposed to lay a railway track from the main line south of Horninglow Street as far as the breweries in High Street to service them.

Under an Act of 1859 the Midland and other railway companies were authorised to construct two branches from the North Staffordshire line in Stretton, one running across Guild Street and High Street and the other under Hawkins Lane, across Anderstaff Lane (later Wetmore Road), and southwards along the west arm of the Trent. The branches met at sidings on the Hay behind the High Street breweries. A separate Act of 1860 authorised a private line from the Guild Street branch to serve Allsopp’s brewery on the north side of Horninglow Street. The construction of the Hay branch was instrumental in the demolition of the old medieval bridge over the Trent and its replacement by a new bridge opened in 1864.

Further lines in the central and eastern parts of the town were laid privately by brewing companies under an Act of 1862 and by the Midland Railway Company under Acts of 1864 and 1867. To serve brewery premises on the west side of town lines were laid by the Midland company in 1874, including one along the disused Bond End canal. Lastly, the London and North Western Railway Company in 1882 made a line along the east side of the Trent and Mersey canal between Shobnall and the Stretton junction.

The below extract from a map produced in 1865 shows the yet disjointed Station Street (now renamed from Cat Street) and Borough Road. It is also interesting to note that the soon to be demolished windmill is still in place on what would become the rear of the Station Hotel. It would also be a few years before Saint Paul’s Church followed by Saint Paul’s Institute and the Liberal Club (eventually destined to become the Town Hall) appeared.

As an ever increasing centre for beer brewing, Burton soon became criss-crossed brewery companies’ private lines and the numerous level crossings became the bain of the town!

New Station (1883)

A construction of a new much needed station was agreed in 1881. The first part of the plan necessitated the Station Bridge to be constructed to join the top of Cat Street (Station Street) to Borough Road, prior to which, there was only a foot crossing. The new station was built 150 yards down the line. It was built as an island platform with bays at each end, with substancial buildings along its length. At the same time, the number of tracks was quadrupled to cater for much greater needs.

Buildings, including freight handling and a booking hall, were built at the upper bridge level. They were built in early English retro-style, partly timbered to look older than they actually were. Access down to the platforms was reached by a wide flight of steps with one side for ascending, the other for descending.

The new station was opened in 1883 and the old station was demolished. It had much larger buildings at the upper level and a large canopy provided shelter at the front.

The distinctive canopy survived pretty much unchanged by the time the above 1910 photograph was taken. Trams had by now replaced horse drawn hanson cabs. The canopy was eventually removed to meet the demand for car parking.

Still little changed by 1960. The tramlines were of course, long replaced by a suitable surface for cars together with improved street lighting. The lattice work of the canopy had been replaced with simpler boarding.

Views of either side of the platform looking in the Branston direction from viewpoints at the upper level which used to be inside the station buildings but now form part of the car park.

And a marvellous wider view to put everything in perspective.

A posed picture by some of the senior staff from the Bass Brewery prior to a trip financed by the company. Bass trips, with other breweries following suit, became legendary with numerous trains being specially commissioned for trips to various seaside resorts.

A view of the distinctive platform clock which I am sure I can remember, together with the news kiosk which did a brisk trade in newspapers, confectionery and cigarettes.

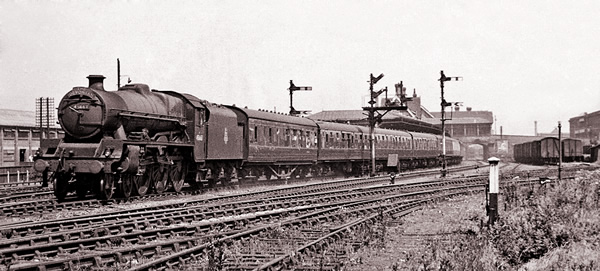

Before being whisked away in old fashioned style. Burton Station still very recognisable as the express train heads south towards Branston.

Two views of the platform in around the 1950s. The above one shows the most familiar view with brewery buildings having taken over the site of the original station. The below view shows that at the time, the platform extended on the other side of the Station Bridge, showing the Station Hotel which still stands, built soon after the station to take advantage of the new prime position.

Just down the line, visible from the station platform in its day, in front of what was Ind Coope Ltd, bottling store (now IMEX Business Park) was a typical signal box.

In 1870 a new locomotive shed was built to the south of the station. This consisted of a roundhouse built round a 42 feet diameter turntable. In 1892 another roundhouse was added, with a 50 feet diameter turntable. In 1923 these were replaced by still larger 57 feet and 55 feet turntables respectively. It can be seen below, still in regular use in 1960 a few years before it fell into disuse.

By 1948 it had 111 locomotives allocated to it, but with the arrival of diesel locomotives it became a sub-depot of Nottingham and was finally closed in 1968.

I am reliably informed that the above photo shows an LMS Class 5-4-6-0 at Burton.

A few photos fortunately providing more or less the same view through the ages with the Ind Coope brewery building in the background.

The second, I am informed by enthusiasts, is an LMS Hughes/Fowler Crab 2-6-0 No. 42826 with the same building little changed other than the signage to advertise its new usage.

The final photo, in more modern times. The building still survives but with less prominence as the town has developed around it.

For the enthusiasts, 5MT number 45140 again taken at Burton. Though having little knowledge of trains, I can very vaguely remember the days when trains looked like proper trains.

And, an early colour photo showing locomotive 64354 sitting at Burton Station – enough to bring the schoolboy out in anyone!

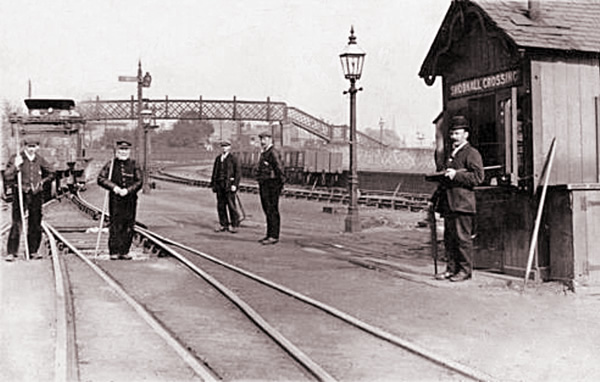

The above photo shows work at what was known as the Shobnall Crossing close to the present day Moor Street bridge.

And at the other, Northern, end of town, a view over Wetmore Sidings.

Only just about making it through quality control – but two photos too good to omit showing the north-bound platform.

Finally, a few more photos towards the end of its life.

One of the very last photographs taken of the distinctive platform building.

Most of the private brewery railway lines were closed between 1963 and 1968 and the tracks were removed, with road transport now far more preferred.

The station was rebuilt yet again in 1971. The booking office remains in around the same place and the platform stairs are largely original to the previous station. The final photos show the present station for comparison.

As the Dissolution continued, many great Abbeys such as Glastonbury, Shaftesbury and Canterbury which had flourished as pilgrimage sites were reduced to ruins. Some were gifted to the Kings most ‘loyal subjects’. In 1539, Abbot Edys was finally forced to surrender Burton Abbey. Rather than being destroyed like most abbeys, it was later gifted, together with extensive grants to lands including what is now Cannock Chase, to Sir William Paget (pictured) – a close adviser to Henry VIII who later became 1st Baron Paget of Beaudesert. This fortunate survival left the abbey one of the largest in the country. The abbot’s probate jurisdiction in Burton also passed to the Pagets, who continued to exercise it until 1858.

As the Dissolution continued, many great Abbeys such as Glastonbury, Shaftesbury and Canterbury which had flourished as pilgrimage sites were reduced to ruins. Some were gifted to the Kings most ‘loyal subjects’. In 1539, Abbot Edys was finally forced to surrender Burton Abbey. Rather than being destroyed like most abbeys, it was later gifted, together with extensive grants to lands including what is now Cannock Chase, to Sir William Paget (pictured) – a close adviser to Henry VIII who later became 1st Baron Paget of Beaudesert. This fortunate survival left the abbey one of the largest in the country. The abbot’s probate jurisdiction in Burton also passed to the Pagets, who continued to exercise it until 1858.

Christianity was introduced to Mercia, one of the Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchies, in 653 AD. A monastery was founded at its capital, Repton. Soon afterwards, a religious settlement was established at Burton by Saint Modwen who hence became its patron saint. She was an Irish noble woman who became an abbess and made a pilgrimage to Rome.

Christianity was introduced to Mercia, one of the Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchies, in 653 AD. A monastery was founded at its capital, Repton. Soon afterwards, a religious settlement was established at Burton by Saint Modwen who hence became its patron saint. She was an Irish noble woman who became an abbess and made a pilgrimage to Rome.