1920s From Above

1920s Burton from Above

Select page to view:

|

|

Burton upon Trent when renown as one of the most significant brewing towns in the country, was famous for having its own internal railway system solely to serve the breweries.

Brewers aside however, the plans were not met with enthusiasm, largely because of the many proposed railway crossing that would disrupt the traffic. In 1859, notices were posted all over the town prompting readers to meet at the Court House in Station Street to sign a petition to the House of Commons “Against such railways crossing the Public Streets”. Slightly surprisingly, one of the signatories was W.H.Worthington (who would eventually go on to become Burton’s first Mayor). This might suggest that the Worthington Brewery could manage without them more than some of its competitors!

As anticipated, the town’s internal railway had become more infamous than famous with vehicle drivers and pedestrians alike by the time it had reached its peak of 32 railway crossings.

The crossing in New Street with Burton General Hospital in the foreground.

A later photo from a little further down from the New Street Crossing above, this time in Duke Street with the ‘new’ wing of the Burton General Hospital behind.

A view of the Station Street crossing in action.

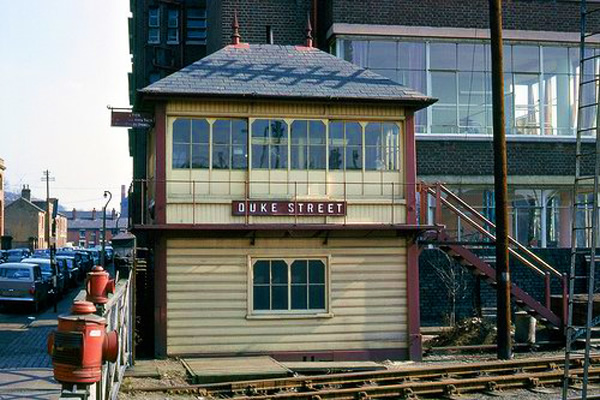

A view of the opposite side of the road reveals one of the more ‘modern’ style of control box.

A later view of the same Station Street crossing. I am not too hot on brewery trains but I CAN say that the car waiting is a 1965 Ford Corsair with its distinctive pointed front.

The present day site of the Station Street crossing still has lots of features that can be picked out from the photos above but even still, it is difficult to image trains running back and forth across the road all day.

The crossing next to the Blue Posts in High Street was some time later immortalised by being featured in an L.S. Lowry painting, ‘The Crossing’.

A reminder that much of the out-lying community of Burton made good use of the train.

Tutbury Station

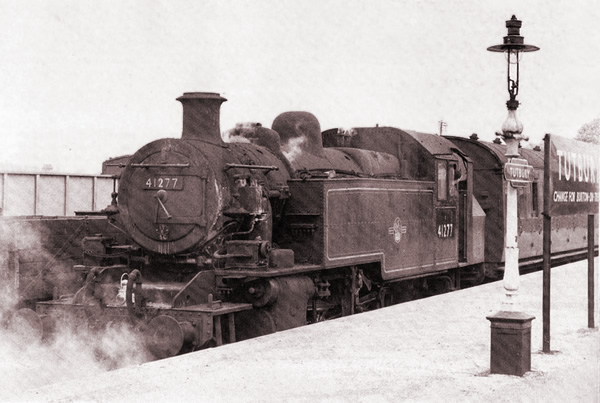

Tutbury Station, probably the most famous of Burton’s out-lying stations because of the revered Tutbury Jinny.

Tutbury Station was built on the Burton upon trent to Uttoxeter branch line and was opened in 1849. The smoking chimney was Nestle on the same site as the existing plant. On the right is a goods shed behind which was a grain warehouse and cattle pen.

In its heydey, the ‘Tutbury Jinnie’ provided eight trains each way on weekdays and two on Sundays. However, as the motor car became more accessible, a survey in 1960 revealed that the service was only carrying an average of twelve passengers and running at a loss of around £7000, which was quite a significant sum at the time. The service managed to survive until it was withdrawn in 1960 when a ceremonious packed last train left Tutbury at 8:12pm on 11th June.

The station was fully closed in 1966 but was re-opened by popular request in 1990 and remains in use today.

Willington Station

The station at Willington, was built on the Derby line which opened in 1859, has also managed to survive and a station on the same site remains in use today.

Willington signal box has of course, long gone. The main Derby line from Burton still goes over Willington bridge but just before Willington on the Derby side, a branch survives which runs over the modern Willington crossing on its way to Tutbury and Uttoxeter.

Barton and Walton Station

The three following photos show the Barton and Walton Station, opened in 1846 on the Derby to Birmingham line.

It was situated between the villages of Barton under Needwood and Walton-on-Trent. The station was closed in 1958 and is now the site of a railway depot.

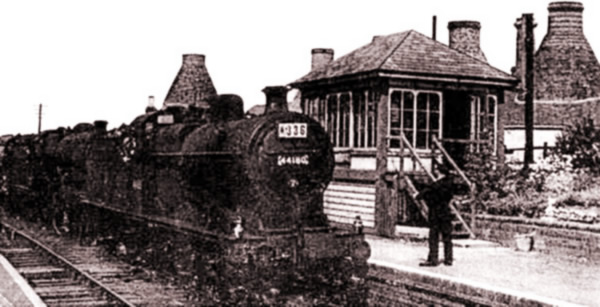

Gresley Station

Gresley Station with a name that will always be associated with railways. It was built a Castle Gresely on the Leicester line, which opened in 1849, but there is little evidence left of it today.

The below view towards the end of its life shows its proximity to the bridge that forms part of the A444.

Moira Station

After Gresley on the way to Leicester came Moira (or Overseal and Moira) Station.

The above photo with both platforms empty suggests that a train has recently departed.

The above photo shows the abandoned station, opened in 1850 – closed in 1964. It was eventually sold for convertion to a private residence.

Swadlincote Station

There was a loop off the Burton to Ashby line that some trains used going through both stations as an alternative to going directly to Burton via Gresley. The below photo shows the Swadlincote Junction signal box.

You could be forgiven for thinking that the above and below photos were different angle shots of the same station. In fact, the above photo is Swadlincote Station and below is Woodville Station. Your eyes are not deceiving you however, the two station buildings are identical mirror images of one another. They were both built by the same builder for exactly the same price.

I wonder if anyone ever woke up with a start and jumped off at the wrong station.

Woodville Station

The pottery adds to the confusion because many would deduce that it was Rowley’s Pottery close to Swadlincote Station but in fact, Woodville had its own Mansfield’s pottery.

The road in Woodville is still called Station Road and on Google earth, it is still fairly easy to pick out the loop where the line used to run going back to Swadlincote although it is very difficult to image trains running around there now.

The Woodville Tunnel, seen above, was between Swadlincote and Woodville and went under the main Ashby Road (A511). Although it is easy to pick out the section now, again, it is almost impossible to image steam trains running under the road.

The above shows Woodville station at its busiest. Two trains heading in opposite directions co-incide with both platforms. A regular using his own shortcut has timed his run to perfection to gain one of the few remaining places.

The above wider view gives a better idea of the size and position of the pottery. Because of the gradient between Swadlincote and Woodville, and hence the above shown tunnel, steam engines were often paired together.

Finally, a wide view from the other side taken patiently as a train builds up steam to depart.

The final photo of Woodville Station is very grainy but is, I think, worth showing. Once again, you can just about make out that there are two steam engines.

Ashby Station

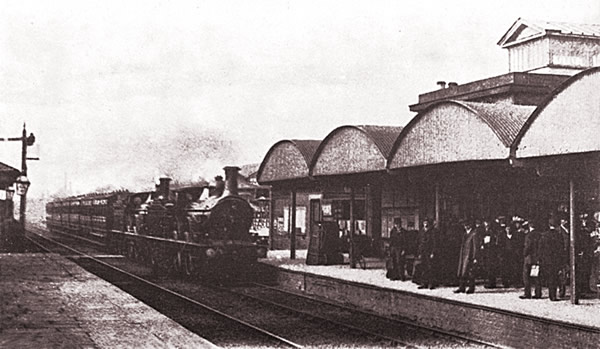

Ashby-de-la-Zouch railway station was too nice a building to fall into disuse. At the time of being built, Ashby was a well-to-do spa town with station to reflect its status.

The Midland Railway opened the station on 1st August 1849 as part of its new line between Swannington and Burton-on-Trent. The station was built partly on the remains of the horse-drawn Ticknall Tramway, which previously connected Ticknall lime quarries with the Ashby Canal.

In 1874 the Midland extended its Derby to Melbourne line to Ashby-de-la-Zouch, partly using the route of the former Ticknall Tramway. The junction with the Leicester to Burton-on-Trent line was just west of Ashby station, so for a time the branch was served by a separate station a short distance from the 1849 building.

Eventually, the station was consolidated with the main platform being the Leicester line. Apologies for the quality of the above image but it does show that it was bustling in its heyday. The stone block above the platform shelter is the rear of the existing building. I am not sure what the tower on top is.

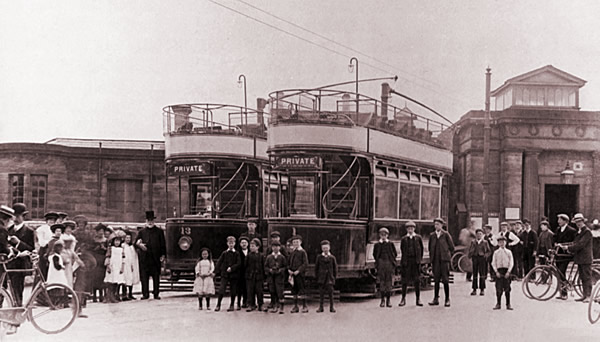

Ashby station forecourt was also a terminus for the 3 ft 6 in gauge Burton and Ashby Light Railway, the tramway between Ashby and Burton upon Trent, built by the MR and closed on 19th February 1927. Tram lines for the Burton and Ashby Light Railway are still visible in the forecourt.

The line became part of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway under the Grouping of 1923. In the nationalisation of transport in Britain in 1948 the line passed to the London Midland Region of British Railways. British Railways withdrew passenger services and closed Ashby station on 7 September 1964.

The building is now Grade II listed.

Drakelow Power Station

I receive many emails thanking me for memories that were long before my time. But the final photo is for my own sheer indulgence. It shows a coal train joining the Leicester Line at the Drakelow junction.

My Nan and Grandad used to live in an upstairs flat on Rosliston Road close to the Drawelow Bridge. My Grandad worked at the Power Station and he explained to me why they were always going one way full of coal and the other empty. From the window, it was possible to see steam rising in time to race to the bridge and watch the train go under and enjoy being surrounded in steam and taking in the smell.

I could almost have taken this photo myself from the days that waving to the driver might result in a wave back. I had never been on a train and this is my sole recollection of trains from the age of steam.

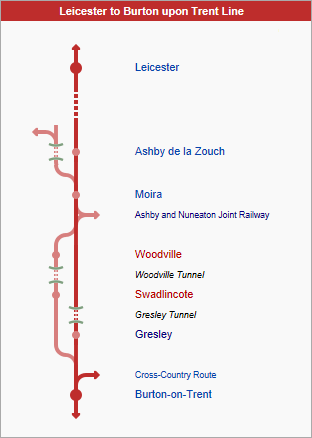

Map

The below map shows the relationship between the local Leicester Line stations. The direct route was through Moira and Gresley to Burton but some trains took a detour between Burton and Moira, missing out Gresley but taking in Swadlincote and Woodville instead,

Old Station (1839)

Burton’s first railway station was opened in 1839 by the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway on its original route from Derby to Hampton-in-Arden meeting the London and Birmingham Railway for London. The station stood at end of what was then called Cat Street, which was eventually renamed in 1844 to the now much more familiar Station Street.

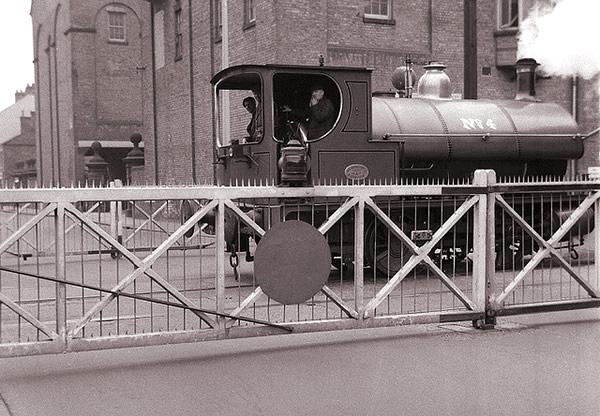

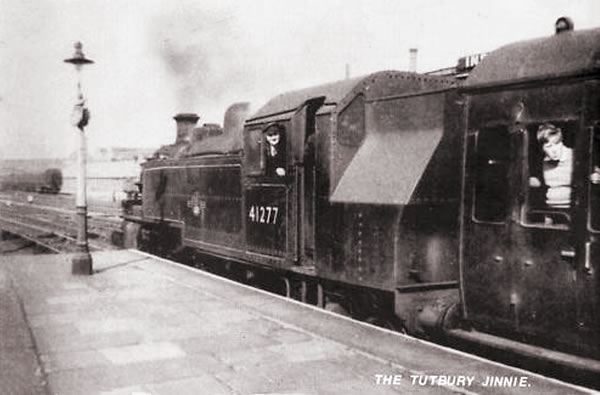

In 1848, the North Staffordshire Railway Company opened a line from Crewe to Derby, with a branch line from Uttoxeter which connected Tutbury and Burton. A small passenger train known affectionately as the Tutbury Jinny, seen below, was a popular sight at the old Burton station. It operated a push-pull service between the two stations.

This later became known as the more colloquial ‘Tutbury Jinnie’ and became important for commuters and shoppers, who travelled from Tutbury to Burton.

In its heydey, the ‘Tutbury Jinnie’ provided eight trains each way on weekdays and two on Sundays. However, as the motor car became more accessible, a survey in 1960 revealed that the service was only carrying an average of twelve passengers and running at a loss of around £7000, which was quite a significant sum at the time. The service managed to survive until it was withdrawn in 1960 when a ceremonious packed last train left Tutbury at 8:12pm on 11th June.

It can be seen above and below in its more ‘modern’ guise in its final years.

Tutbury station was fully closed in 1966 but was re-opened by popular request in 1990 and remains in use today.

A year after the previous line, in 1849, the Midland Railway Company, which now owned and operated the Birmingham to Derby line, opened a line from Burton to Leicester which crossed the Trent by a substancial viaduct still known today as the Leicester Line Bridge.

Burton’s main streets became congested by drays delivering barrels to the station from the breweries which were mostly located near the river. As early as 1853 it was proposed to lay a railway track from the main line south of Horninglow Street as far as the breweries in High Street to service them.

Under an Act of 1859 the Midland and other railway companies were authorised to construct two branches from the North Staffordshire line in Stretton, one running across Guild Street and High Street and the other under Hawkins Lane, across Anderstaff Lane (later Wetmore Road), and southwards along the west arm of the Trent. The branches met at sidings on the Hay behind the High Street breweries. A separate Act of 1860 authorised a private line from the Guild Street branch to serve Allsopp’s brewery on the north side of Horninglow Street. The construction of the Hay branch was instrumental in the demolition of the old medieval bridge over the Trent and its replacement by a new bridge opened in 1864.

Further lines in the central and eastern parts of the town were laid privately by brewing companies under an Act of 1862 and by the Midland Railway Company under Acts of 1864 and 1867. To serve brewery premises on the west side of town lines were laid by the Midland company in 1874, including one along the disused Bond End canal. Lastly, the London and North Western Railway Company in 1882 made a line along the east side of the Trent and Mersey canal between Shobnall and the Stretton junction.

The below extract from a map produced in 1865 shows the yet disjointed Station Street (now renamed from Cat Street) and Borough Road. It is also interesting to note that the soon to be demolished windmill is still in place on what would become the rear of the Station Hotel. It would also be a few years before Saint Paul’s Church followed by Saint Paul’s Institute and the Liberal Club (eventually destined to become the Town Hall) appeared.

As an ever increasing centre for beer brewing, Burton soon became criss-crossed brewery companies’ private lines and the numerous level crossings became the bain of the town!

New Station (1883)

A construction of a new much needed station was agreed in 1881. The first part of the plan necessitated the Station Bridge to be constructed to join the top of Cat Street (Station Street) to Borough Road, prior to which, there was only a foot crossing. The new station was built 150 yards down the line. It was built as an island platform with bays at each end, with substancial buildings along its length. At the same time, the number of tracks was quadrupled to cater for much greater needs.

Buildings, including freight handling and a booking hall, were built at the upper bridge level. They were built in early English retro-style, partly timbered to look older than they actually were. Access down to the platforms was reached by a wide flight of steps with one side for ascending, the other for descending.

The new station was opened in 1883 and the old station was demolished. It had much larger buildings at the upper level and a large canopy provided shelter at the front.

The distinctive canopy survived pretty much unchanged by the time the above 1910 photograph was taken. Trams had by now replaced horse drawn hanson cabs. The canopy was eventually removed to meet the demand for car parking.

Still little changed by 1960. The tramlines were of course, long replaced by a suitable surface for cars together with improved street lighting. The lattice work of the canopy had been replaced with simpler boarding.

Views of either side of the platform looking in the Branston direction from viewpoints at the upper level which used to be inside the station buildings but now form part of the car park.

And a marvellous wider view to put everything in perspective.

A posed picture by some of the senior staff from the Bass Brewery prior to a trip financed by the company. Bass trips, with other breweries following suit, became legendary with numerous trains being specially commissioned for trips to various seaside resorts.

A view of the distinctive platform clock which I am sure I can remember, together with the news kiosk which did a brisk trade in newspapers, confectionery and cigarettes.

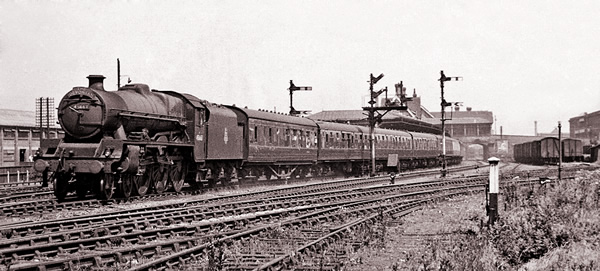

Before being whisked away in old fashioned style. Burton Station still very recognisable as the express train heads south towards Branston.

Two views of the platform in around the 1950s. The above one shows the most familiar view with brewery buildings having taken over the site of the original station. The below view shows that at the time, the platform extended on the other side of the Station Bridge, showing the Station Hotel which still stands, built soon after the station to take advantage of the new prime position.

Just down the line, visible from the station platform in its day, in front of what was Ind Coope Ltd, bottling store (now IMEX Business Park) was a typical signal box.

In 1870 a new locomotive shed was built to the south of the station. This consisted of a roundhouse built round a 42 feet diameter turntable. In 1892 another roundhouse was added, with a 50 feet diameter turntable. In 1923 these were replaced by still larger 57 feet and 55 feet turntables respectively. It can be seen below, still in regular use in 1960 a few years before it fell into disuse.

By 1948 it had 111 locomotives allocated to it, but with the arrival of diesel locomotives it became a sub-depot of Nottingham and was finally closed in 1968.

I am reliably informed that the above photo shows an LMS Class 5-4-6-0 at Burton.

A few photos fortunately providing more or less the same view through the ages with the Ind Coope brewery building in the background.

The second, I am informed by enthusiasts, is an LMS Hughes/Fowler Crab 2-6-0 No. 42826 with the same building little changed other than the signage to advertise its new usage.

The final photo, in more modern times. The building still survives but with less prominence as the town has developed around it.

For the enthusiasts, 5MT number 45140 again taken at Burton. Though having little knowledge of trains, I can very vaguely remember the days when trains looked like proper trains.

And, an early colour photo showing locomotive 64354 sitting at Burton Station – enough to bring the schoolboy out in anyone!

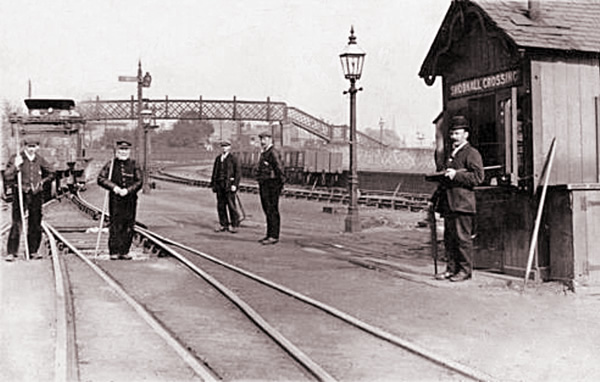

The above photo shows work at what was known as the Shobnall Crossing close to the present day Moor Street bridge.

And at the other, Northern, end of town, a view over Wetmore Sidings.

Only just about making it through quality control – but two photos too good to omit showing the north-bound platform.

Finally, a few more photos towards the end of its life.

One of the very last photographs taken of the distinctive platform building.

Most of the private brewery railway lines were closed between 1963 and 1968 and the tracks were removed, with road transport now far more preferred.

The station was rebuilt yet again in 1971. The booking office remains in around the same place and the platform stairs are largely original to the previous station. The final photos show the present station for comparison.

The Sinai Park site, due to its elevated strategic position, has a history dating back to Roman times and before. The hilltop site enjoyed commanding views over the Trent Valley in both directions making it an ideal outpost being mid-way on a day’s march from Derby to Lichfield.

The Saxons also used the location as a stronghold and, in Medieval times, the fortified manor of the de Schobenhale family, dominated the area. A large house preceded the existing one but the most evident feature from this period is the 14th Century moat, dated by one source to 1334, which pre-dates the house and has special importance. The de Schobenhales gave Sinai Park to the monks of Burton Abbey in 1004. At the time, this was one of the most significant monastic seats in England.

In 1334, Abbot William Bromley of Burton Abbey gave five days indulgence from the bloodletting at Schobenhale Park with increased allowance of bread and beer for convalescence and recuperation. The origin of ‘Sinai’ is thought to be ‘saignée’, the French word for bloodletting and nothing to do with the Biblical ‘Mount Sinai’ due to its elevation. On a 1410 map, it is however, marked as ‘Seyne Park’.

Around this time the monks were responsible for establishing two timber houses on the site which would later form the two wings of one large building when the two became joined together by a central section. There has long been a legend of a secret tunnel between Sanai and Burton Abbey but this is pretty clearly nonsense.

Rest and recuperation seems to have gained quite a wide definition by the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. By then, the Abbot had his own parlour in the northeast wing, his monks were hunting for deer in the park and engaging in a number of highly frivalous activities, which even resulted in the occasional murder. These were cited in some of the reports back to Henry VIII to re-enforce the need for a dissolution.

As a result of the Dissolution, Sinai was included in the many estates acquired by the William Paget family in 1546. William Paget, one of Henry VIII’s chief ministers, was also installed as the first Baron of Beaudesert. The Paget family would continue to own Sinai for almost 400 years during which time, they would also become earls of Uxbridge and marquises of Anglesey.

Sinai was never the Pagets’ main house. This was originally their country house at Beaudesert and eventually their grand new home in Anglesey, Plas Newydd, designed in the 18th century by James Wyatt. Even within Burton, the Manor House (now offices close to the Winery) was their preferred residence so Sinai was used principally as a hunting lodge with its own deer park. It did though, enjoy a number of important guests including the earl of Essex during Elizabeth I’s reign.

The main central section which joined the two existing wings together to form a much larger property, was built by the Pagets in 1605 which elevated the house to a much grander status. In the 1700s there was still more building work with large Tudor-style chimneys being erected which added further to its grandeur. Also from this period is what was then a very fashionable plunge pool (waterfall lake), built in the grounds, using as its source the Chalybeate well below the house.

Reconstruction of Sanai Park House in its heyday

Reconstruction of Sanai Park House in its heyday

In 1732, a more impressive bridge over the moat was built to replace an existing one on the same site. The original bridge was one of four similar ones and the location of a skirmish between the Paget men and the Bagots of neighbouring Blithfield during the English Civil War.

While the architect, James Wyatt, was being commissioned by the Pagets to build a new principal seat, Plas Newydd on the Isle of Anglesey, his brother William became the tenant of Sinai. William’s daughter was married there to John Smith who was working with James Brindley on the new canal network, and his son who took over the tenancy and stewardship of the house but was eventually fired and asked to leave for spending too much unauthorised money on its development.

The last Paget to own Sinai was Henry Cyril Paget, 5th Marquess of Anglesey (1875 – 1905) who was known as ‘Toppy’. The ‘Black Sheep’ of the Paget family; a British Peer notable during his short lifetime for squandering away the Paget inheritance on a lavish social life and amateur theatricals accumulating massive debts.

On the death of his father in 1898, as well as Sinai Park, he inherited the title and family estates which included Beaudesert in Staffordshire, formely the family’s principal residence, Plas Newydd on the Isle of Anglesey and other estates in Derbyshire and Dorset totalling over 30,000 acres and providing an annual income of £110,000. Someone would have to work very hard to make this fail!

He spend very little time at Sinai which, on his death, was one of many parts of the estate that had to be sold as part of the settlement of family debt. After being sold, the house was converted to six ‘cottages’. For a while, it provided a billet accommodation for the RAF. In a gravely deteriorated state, it eventually slumped to becoming a makeshift shelter for pigs, sheep and hens.

It was described as “The most important house in England to be in such a state”. In recent years, thankfully, it has undergone major restoration with help from the English Hertitage and is listed as a Grade II* listed building. The 13th century moat is separately listed as an ancient monument.

Adjacent to Sinai Park House is the present day farm house and associated buildings.

Christianity was introduced to Mercia, one of the Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchies, in 653 AD. A monastery was founded at its capital, Repton. Soon afterwards, a religious settlement was established at Burton by Saint Modwen who hence became its patron saint. She was an Irish noble woman who became an abbess and made a pilgrimage to Rome.

Christianity was introduced to Mercia, one of the Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchies, in 653 AD. A monastery was founded at its capital, Repton. Soon afterwards, a religious settlement was established at Burton by Saint Modwen who hence became its patron saint. She was an Irish noble woman who became an abbess and made a pilgrimage to Rome.

She, together with two other accompanying nuns Lazar and Althia, visited Burton on the way and founded a church dedicated to God and Saint Andrew on an island on the river Trent. She named the island Saint Andrew’s Isle, or Andressey. They stayed for seven years before continuing to Rome.

On her return journey, she built another church across the river at the foot of Mount Calvus, later known as Scalpcliffe Hill, this time dedicated to Saint Peter on the site of the current church in Stapenhill. She undertook further missionary work in Scotland, where she died at a place called Lanfortin near Dundee. A traditional story tells that on her death, her companions saw her soul taken to heaven by silver swans, which became her emblem, as depicted by the large White Swan in Stapenhill gardens. Her body was returned to Burton for burial; she was reputed to be 130 years old. A shrine to Saint Modwen was built at the church on Andressey but this was destroyed by the Danes in 874 AD who left their heritage on a number of place names, most notably, Broadholme and Horsholme which are the names of two of Burton’s other neighbouring islands; ‘holme’ being Danish for water meadow or island. Her remains were reputedly recovered and ended up at Burton Abbey when it was established in 1002 AD by Wulfric Spot, a Saxon nobleman. A new shrine was established in the Abbey church and was reputedly visited by William the Conqueror.

Some of Modwen’s alleged remains were transferred from the chapel on Andresey to Burton abbey and a shrine built there. The move evidently took place between 1008, when the abbey’s dedication was recorded as ‘St. Benedict and All Saints’, suggesting that Modwen’s bones were not then within the abbey church, and the abbacy of Leofric (1051-66) who despoiled the shrine.

There is known to have been an altar to Modwen in the abbey church by the time of Abbot Geoffrey Malaterra (1085-94). An undated grant by William I (1066-87) makes the strong suggestion that he visited her shrine. The Abbot promoted Saint Modwen and increasing her importance.

When Abbot Geoffrey took over Burton Abbey in 1114 he knew little about the saint whose bones his Abbey possessed and was very intrigued to find out more. He re-built the shrine and wrote to Ireland for information, he was sent a ‘Life of Modwenna’ written by Conchubranus (or Conchobhar), an itinerant Irishman searching for materials about an Irish abbesses. Abbott Geoffrey edited this and added a few stories of Modwen’s time in Burton and telling of her posthumous miracles. It was called ‘Life of Saint Modwenna’.

Amazingly, the Conchubranus book still survives and has recently been edited and translated by Professor Robert Bartlett of Saint Andrew’s University. For the first time we know what the monks believed and taught about Modwen. Conchubranus’ book contains references to Modwen’s time in Burton, of her establishing both churches, and talks about the Burton monks possessed her bones and her name. In Conchubran’s time in Ireland, Burton was also known as ‘Mudwennestow’, meaning ‘Modwen’s holy place’.

Some relics of Saint Modwen were re-discovered in 1201 which prompted a renewed interest in her cult. Additional miracles were attributed to her, and she was depicted on the seal of Abbot Nicholas (1216-22). A new shrine was built in the abbey church in the early 15th century, and it was probably that shrine which by the 1530s had an image of the saint with a red cow and a staff said to be helpful to women suffering labour pains.

By the late 13th century, Saint Modwen was known in monasteries with earlier links to Burton including Winchester, where Abbot Geoffrey of Burton had been prior; Reading, where Abbot William Melburne had been a monk; and Wherwell nunnery, Hants. near Winchester. In addition, the two cathedrals of Canterbury and Salisbury have relics of her. No other English parish church however, has been dedicated to her outside of Burton, although there was a small chapel dedicated to her in Offchurch, Warwickshire. In the 1530s there was an image to Modwen in Ashbourne church, Derbyshire; she was also depicted in medieval window glass, mentioned in 1798, at Pillaton Hall, in Penkridge.

When the chapel on Andresey was dedicated in the early 13th century by Bishop Geoffrey Muschamp, it was called Saint Andrew’s church, and its keeper was given 1s. a year by Abbot William Melburne. There was still an altar dedicated to Saint Modwen on the island by 1280. When the chapel was rebuilt by Abbot Thomas Feld in the late 15th century, it was known as St. Modwen’s and contained her supposed tomb.

In Tudor times, St Modwen’s Holy Well was in a chapel on Andrew’s Island between two branches of the River Trent at Burton. It was famous for the cure of King’s Evil and other extraordinary cures. The water had long been used by the monks for brewing the famous Burton Ale and pilgrims came to partake of the water and possibly the ale too. The offerings received from the pilgrims visiting the shrine in the 1530s just before the dissolution, was around £2 a year.

The Abbey was the centre of life in Burton until Henry VIIIs Dissolution in 1538. During this period, the Saint Modwen cult in Burton was officially suppressed.

Sir William Bassett was at Meynell Langley, Derbyshire, at the end of August 1538 when he received instructions from Thomas Cromwell “that such images as you know… so abused with pilgrimages or offerings… you shall for avoiding that most detestable offence of Idolatry forthwith take down”. Sir William carried out his task and replied to Cromwell, as follows:

Right honourable my inespecial good lord, according to my bounden duty and the tenor of your lordship’s letter lately to me directed, I have sent unto your good lordship by this bearer, my brother Francis Bassett, the images of St Anne of Buxton and St Modwen of Burton upon Trent which images I did take from the places where they did stand, and brought them to my own house within 48 hours after contemplation of your said lordship’s letter, in as sober manner as my little and rude wits would serve me. And for that there should no more idolatry and superstition be there used I did not only deface the tabernacles and places, where they stand but also did take away the crutches, shirts and sheets with wax offered, being things that did allure and intice the ignorant people to the said offerings, also giving the keepers of both places admonition and charge that no more offerings should be made in those places till the King’s pleasure and your lordships be further known in that behalf. My lord, I have locked up and sealed the baths and wells at Buxton and none shall enter to wash them till your lordship’s pleasure be further known. Whereof I beseech your lordship that I may be ascertained again at your pleasure and I shall not fail to execute your lordship’s commandment to the uttermost of my little witt and power. And the trust that they did put in those images and the vanity of the things, this bearer, my brother can tell your lordship better at large than I can write for he was with me at the doing of all and in all places, as knoweth good Jesus, whom ever good lordship in his blessed keeping. Written at Langley with the rude and simple hand of your assured and faithful orator and as one ever at your commandment, next unto the King to the uttermost of my little power.

Signed William Bassett (Knight)

On 1st September, Thomas Thacker, Steward to Cromwell, wrote to his Master telling him that Francis Bassett had delivered to Austin Friars (Thomas Cromwell’s main residence) in London, “the image of St Modwyn with her red cow and her staff which women labouring of child in those parts were desirous to have with them to lean upon and to walk with“. This is the best available description of the statue.

Thomas Cromwell fell from grace a few years later and was arrested being accused of many crimes, most significantly treason. Cromwell was condemned to death without trial and beheaded on Tower Hill on 28 July 1540 (the day of the King Henry VIII’s marriage to Kathryn Howard). Following his death, an inventory was taken of his belongings which showed an extensive collection of treasures that had been confiscated from the church for supposed destruction. It has not been possible to identify the images of St Anne and St Modwen mentioned in the letter from Sir William Bassett.

Following removal of the shrine, the keeper was ordered not to accept any more offerings. Some elements of the cult, however, persisted. The name Modwen, which had some popularity before the Reformation, continued to be given to girls in Burton until at least 1585. Saint Modwen’s well on Andresey Island was recorded in 1686, still there in at least 1738, was said to work great cures. There was a 16th century attempt to rename the Island, Saint Modwen’s Isle, but this did not stick and it reverted to Andresey (Andrew’s Island).

When the chapel on Andresey passed to the Pagets as lords of Burton manor in 1546, it measured 60 by 27 feet. It was still standing in 1699 and possibly as late as 1837, but by 1857 the chapel site had gone. The area around the chapel was known as St. Modwen’s Orchard by 1760, when it was marked by a water-filled ditch. The ditch can just be seen today next to what is now known as the Cherry Orchard.

A modern monument to commemorate Saint Modwen was erected on Andressey Island at the end of the twentieth century. You may even have seen it but not registered who, or even what, is is supposed to depict. I certainly did! Strangely, it is half a mile away from where the original Saint Andrew’s Church and later Saint Modwen’s chapel stood.

The parish church still celebrates Saint Modwen’s day on 29th October (although the date appears to have been changed a number of times over the centuries).

One of Abbot Geoffrey’s stories in Professor Bartlett’s translation is included below.

A Miracle of St. Modwen – abridged from the ‘Life of Saint Modwenna’ by Abbot Geoffrey of Burton (c1120 AD), translated by Professor Robert Bartlett.

When St Modwen returned to England from Rome she came to the place called Scalpcliffe and saw there, by the hill, an island in the River Trent. It was secluded from men and had an isolated hermitage, and she loved the place very much. She stayed there for seven years and built a church dedicated to St. Andrew. To this day the island is known as Andressey, or Andrew’s Isle. At that time the area was a desolate wilderness, with woods and wild animals, but no people.

There lived at Breedon a saintly hermit who heard of Modwen’s reputation and used to visit her. He brought her writings on the lives of the saints which they read together, encouraging each other in their faith with the examples of the saints.

One day the hermit arrived but had forgotten the book. Modwen was grieved, and they decided to send for it. The hermit instructed two of Modwen’s companions where the book might be found, and Modwen instructed the two virgins to get into a boat and make all speed to fetch the book. They were rowing down the river when a strong wind sprang up which caused great waves on the Trent and filled the girls with fears of drowning and death.

When they reached a place called Leigh the wind got up further and they leant to one side and the boat overturned. They sank to the bottom of the river, and were trapped under the boat.

Modwen and the hermit began to grow anxious that they had been a long time. The thought occurred to Modwen that perhaps they had been drowned. She was desolate and blamed herself for having sent them and held herself responsible for their deaths. But the hermit consoled her, and suggested that they turned to prayer. They prostrated themselves on the ground and tearfully prayed to God for the lives of the girls. At length a bell rang and they rose, and noticed that a dry path had been miraculously opened up on the river bed. The water was divided in an astonishing manner into two parts, standing like a wall to the right and the left of the path.

Modwen and the hermit set off at once down the path on the river bed and came to the upturned boat. On one side of it the girls’ fingers were visible where they had clutched at the gunwale of the boat. The hermit tried to lift the boat but could not. It was as heavy and immovable as if it had grown roots into the river bed. He asked Modwen to try. She did so and the boat lifted as quickly and easily as if it had no weight at all. They found the two girls alive and well, safe and sound, preserved by the grace of God. There was mighty rejoicing and they all gave thanks to Almighty God for the miraculous saving of the girls, for his great wonders and the great marvels he had performed.

Once the boat was turned right way up they all climbed in and at once the waters rushed back into the river bed and bore them along with waves so that it should be clearly understood that God himself had divided the waters and saved the girls in answer to the prayers of the two saints.

A new magistrates’ court and police station were designed by local architect, Henry Beck and built by local builder, Richard Kershaw. It opened in Horninglow Street in 1910.

Select page to view:

Borough magistrates were first empanelled in 1887, meeting weekly in the same place as the petty sessions’ justices but on a different day.

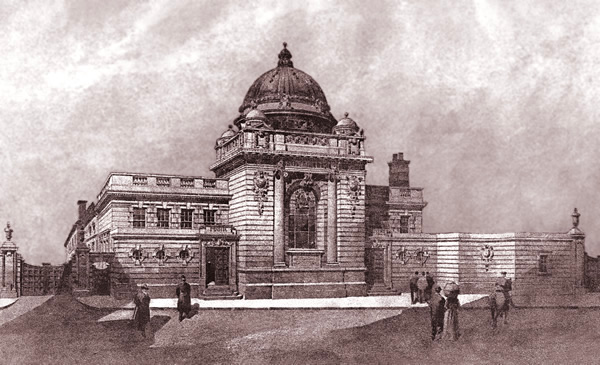

A new magistrates’ court and police station were designed by local architect, Henry Beck. The above architectual drawing, which shows the impressive building, appeared in the 1910 Royal Academy Exhibition. Local builder, Richard Kershaw, was selected to construct the building having completed both the new Fire Station and General Post Office in New Street a few years earlier. Reflecting the confidence of the town at the time, it was constructed from the best quality Portland Stone.

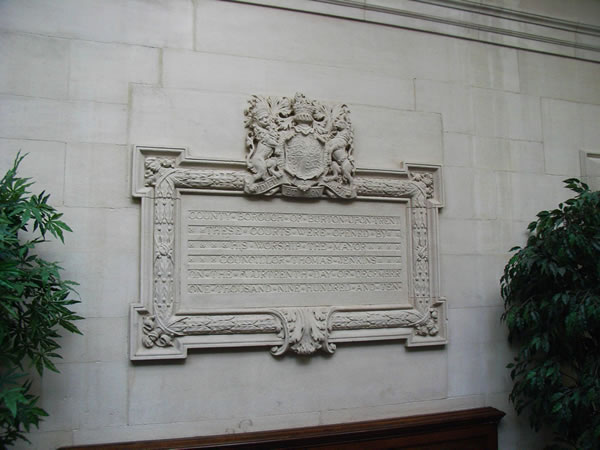

A foundation stone can be found at the front of the building that reads:

THIS STONE WAS LAID BY ALDERMAN CHARLES TRESISE (MAYOR OF BURTON UPON TRENT) ON THE 24TH DAY OF MAY 1909

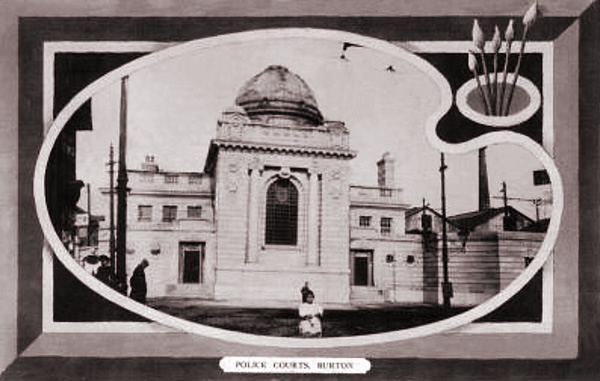

Shortly after the court was opened, this ‘Police Courts, Burton’ artistic ‘pallet style’ postcard was produced. I don’t personally like it at all but it is included here because it provides one of the best available views of the right side of the building with the tramway depot visible at the rear.

The surrounding area was a little different in this photo around 1911. Tantalizingly, the design of the right hand section has now been changed for some reason.

Originally, there was simply a gate on the left providing access to the police station. A property was eventually demolished to make a road to provide access and parking for the new police station. The new road also provided access to the drill hall.

The leaded dome… Burton’s answer to Saint Paul’s Cathedral!

Aside from the expensive materials, top quality stonework was incorporated, again, produced by local craftsmen. It was not a case of having to look afield for expert stoneworkers; Burton was a very up and coming town and it was more the case that expert craftsmen moved to the town knowing that they were likely to find the requirement for high quality work.

The stained glass window, though not very visible from the outside, bears Burton’s coat-of-arms. It would be nice to get a photo from the inside on a suitably sunny day.

The ‘Public’ door which I dare say many have entered with a degree of trepidation. On the other side of the building is another matching door with stonework informing ‘JUSTICES’.

The location was selected to make the most of the expensive building, positioned to provide a strong focal point visible for the whole of Guild Street, which it remains today.

An interesting feature is that once the building was surveyed, it was discovered that it would be impossible for trams to enter and leave the existing depot which was to be its new neighbour. Rather than make expensive alterations to the tramway and depot, it was decided to rotate the whole building by 12 degrees. It is not immediatley obvious from the road but the above aerial view shows it very clearly.

The former Burton Police Station occupied part of what is now the car park at the rear of the old court.

A separate quarter sessions for the county borough was granted by royal charter in 1912. It was abolished under the Courts Act, 1971, but Burton remained the meeting place for petty sessions.

A painting of ‘Burton Magistrates Court and Police Station’ was produced by C. Sheldon in 1993

On the site where the tramway depot once stood is the present day complex, opened in 1991, which includes Burton police station, magistrates court office block leaving the once proud building looking a little forlorn, not knowing quite what to do with itself in the world that has overtaken it.

From the inside of the new complex, it is a fairly seamless passage into the old Court 1 which is still used to full capacity for the most serious magistrate cases.

The new ‘Charrington House’ on the corner of Guild Street across the road from the church was build with a large mirrored frontage to provide motorists with an attractive reflection of the old court building.

The very impressive Magistrate’s chair with Baroque styling based on the design of the Old Bailey. It is very easy to imagine a red gowned, white wigged High Court judge sitting here ready to announce sentence.

The very impressive Magistrate’s chair with Baroque styling based on the design of the Old Bailey. It is very easy to imagine a red gowned, white wigged High Court judge sitting here ready to announce sentence.

The Old Bailey judge’s chair for comparison.

The Old Bailey judge’s chair for comparison.

Court 1 is still in very regular use and is little changed, except probably, for the protective glass around the dock.

Court 1 is still in very regular use and is little changed, except probably, for the protective glass around the dock.

The Old Bailey Courtroom for comparison.

The Old Bailey Courtroom for comparison.

A view from the Magistrates bench

A view from the Magistrates bench

The dock itself looks almost as intimidating as the bench does in the other direction!

The dock itself looks almost as intimidating as the bench does in the other direction!

The two pairs of double doors have a wonderful feel about them.

The two pairs of double doors have a wonderful feel about them.

The Court clock sports the name T. Worthington

The Court clock sports the name T. Worthington

A row of circular windows add to the court’s character

A row of circular windows add to the court’s character

A view of a corner of the ceiling

A view of a corner of the ceiling

And finally, a view of the impressive skylight

And finally, a view of the impressive skylight

The original waiting room

The original waiting room

And the original waiting room benches where many an anxious wait would have been experienced

And the original waiting room benches where many an anxious wait would have been experienced

Columns which add to the elegance of the building

Columns which add to the elegance of the building

And lovely attention to detail

And lovely attention to detail

Admiring the doors, it is easy to forget the dread they may have held for some

Admiring the doors, it is easy to forget the dread they may have held for some

Stonework in the waiting room proudly informs:

Stonework in the waiting room proudly informs: Slightly disappointingly, this is the ceiling directly under the impressive dome. I was rather hoping to be able to see the inside of the dome

Slightly disappointingly, this is the ceiling directly under the impressive dome. I was rather hoping to be able to see the inside of the dome

A second clock to match the one in Court 1

A second clock to match the one in Court 1

The impressive window that can be seen from the front of the court

The impressive window that can be seen from the front of the court

The stained glass window sports the Burton coat of arms and moto

The stained glass window sports the Burton coat of arms and moto

The modern day Court 2 has a much less intimidating feel

The modern day Court 2 has a much less intimidating feel

Court 3, used for the least serious and family cases, feels almost like a meeting room

Court 3, used for the least serious and family cases, feels almost like a meeting room

The new waiting room

The new waiting room