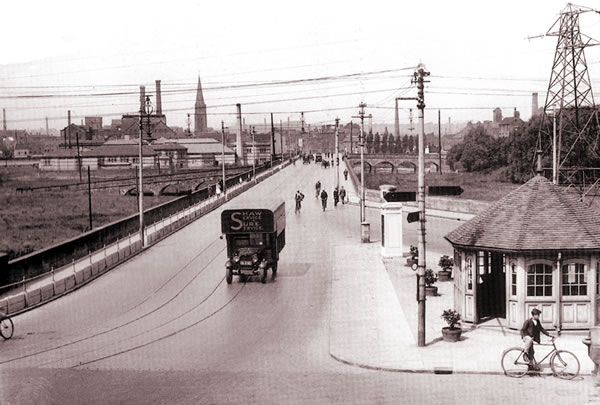

Trent Bridge – Early History

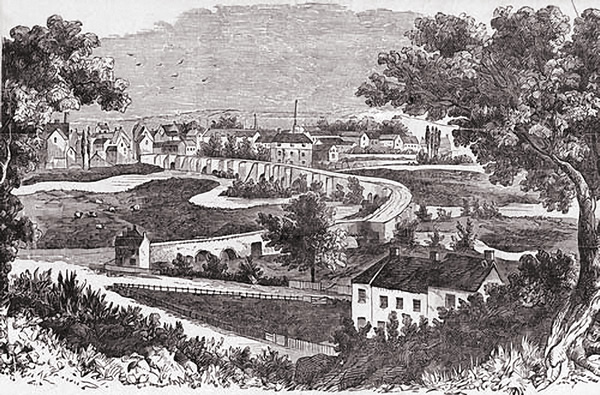

The origin of the old bridge on the north side of Burton is not known, but it is certain that for a long time it ranked amongst the wonders of the land. In the early records of the Abbey there is reference made to a sum of money being set apart for the bridge, but this is thought to be for the repairing of it, not for the building.

There seems to have been a bridge of sorts on the site before the Abbey was established in 1004 AD. For many years after the Abbey was built, High Street, then called Old Street and later Long Street, consisting of very little beside two sloping banks and a ditch between them. There was little else to Burton aside from the Abbey. Some antiquarians even claim that the bridge is over two thousand years old, and that the Icknield Road, stretching from Derby to Ashby, must have crossed it. If that be true, it gives much credit to Roman building skill and materials.

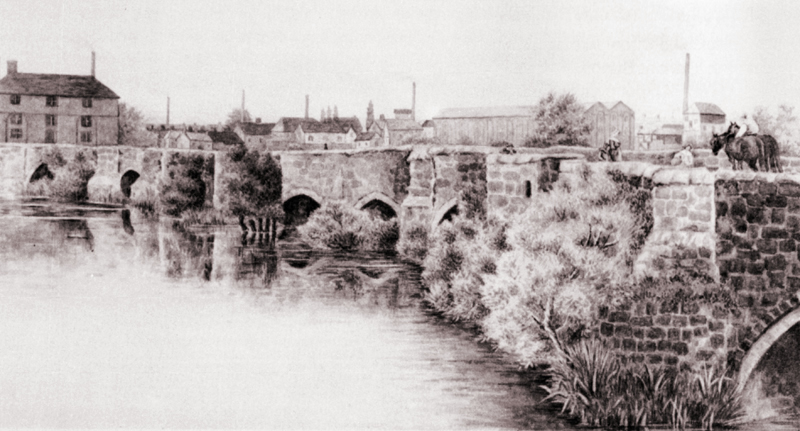

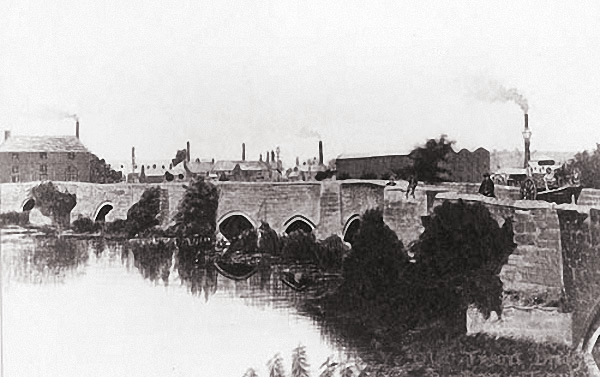

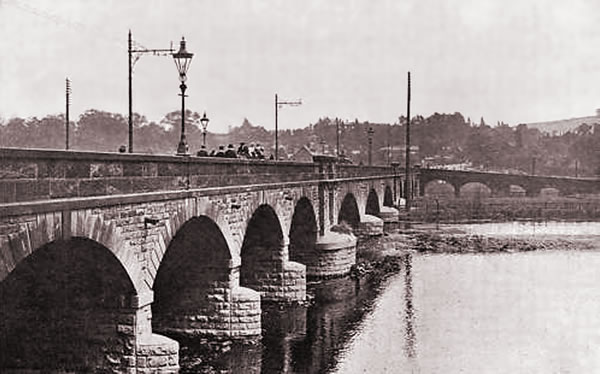

There was certainly a substancial bridge on the site by the early 12th century. A bridge keeper was recorded as holding land on the Winshill side. It is not certain whether it fully spanned the river at this time but it certainly did by the end of the 12th century by which time, burgage plots were established in Horninglow Street, ‘west of the great bridge’. It was probably built of stone, or at least had stone footings, although the first surviving mention of a stone bridge is from 1322. The exact form of the structure is unknown but providing that it was not later substantially altered it would have been as described in the 18th century: running north from Winshill before turning west across the river and the west arm, the bridge was then 515 yards long and 15 feet wide and had 36 arches. By the 1590s water no longer passed through two of the arches where land had silted up at the south end of Burton meadow, creating Umpler green. The east end of the bridge was widened in 1831, and in 1839 the first two arches on that side were filled in.

The west end of the bridge originally terminated with a causeway on the south side of which cottages had been built by 1550. In 1835 there were three houses there and four on the north side. The causeway was raised in the later 1750s, after the road had been turnpiked, and two low arches were inserted as culverts.

Grants of land and bequests of money for the upkeep of the bridge are recorded occasionally in the Middle Ages, and in 1546 the endowment comprised three houses and a small amount of land and meadow, worth 21s 4d a year. The abbey seems to have taken no formal responsibility for maintaining the bridge and much of the money needed for repairs came from alms, presumably collected by a chaplain who maintained a bridge chapel. When part of the bridge was swept away by flood in 1284 John of Norfolk, who was acting as keeper of the works of the bridge, was given royal protection to beg for alms to repair it, as was the keeper in 1324. A grant of pontage made in 1383 was to a body of trustees, including a chaplain who may have been the bridge keeper. John of Norfolk, described as a ‘monk’ in the royal grant of 1284, and a ‘bridge monk’ recorded in 1396 are unlikely to have been monks of Burton abbey, and were almost certainly lay hermits, possibly following the rule of St. Paul: a house called the Hermitage in 1546 stood at the west end of the bridge on its north side, opposite the chapel.

In 1441 the abbot and leading townsmen appointed a layman as keeper and proctor of the bridge for a 30 year term, and a layman was appointed for life in 1493. In 1527 an appeal for funds was launched by the abbot, the prior of Tutbury, George, Lord Hastings, and local gentry.

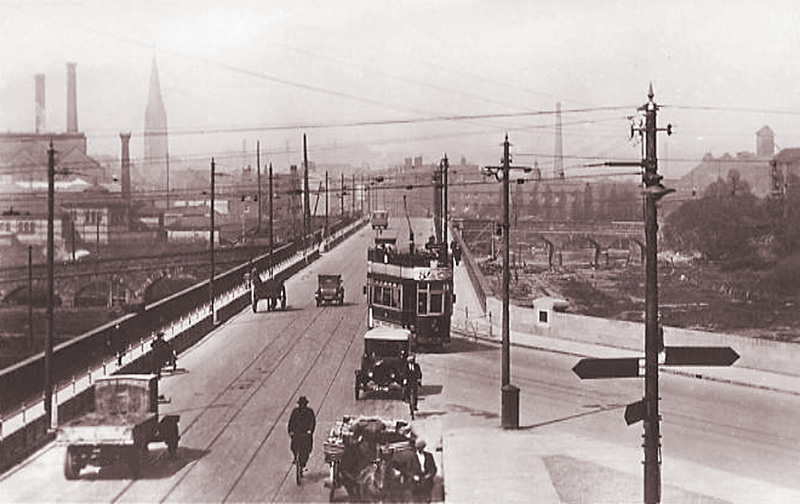

Some of the £20 a year that Burton college was obliged, probably from its establishment in 1541, to spend on making and repairing roads may have been applied to the upkeep of the bridge. At its dissolution in 1545 the college was paying 33s. 4d. a year to a bridge master named William Mason (or Edge), who seems to have been a stone mason retained originally by the abbey; he was still paid a fee by the Paget family in the later 1560s. The annual cost to the manor of maintaining the bridge was estimated at £16 13s. 4d. in 1585. The Pagets evidently assumed responsibility for the bridge, and the obligation was specifically included in the Crown’s grant to William Paget of his father’s forfeited estates in 1597. The cost of repairs was a constant drain on the manor in the 17th and 18th centuries, and when the road over the bridge was turnpiked in 1753 the earl of Uxbridge was awarded £20 a year from the tolls for bridge repair. It remained the lord’s responsibility until 1864.

Bridge Chapel

There was a bridge chapel by the 1260s, and its dedication to St. James was recorded in 1332. On the eve of the Reformation services were being celebrated there by the town’s guild priests. The chapel stood at the south-west end of the bridge and had a south door onto Burton hay. There was also a cross at the east (now Winshill) end of the bridge in 1598. The chapel, having fallen into disrepair, was demolished in 1777.

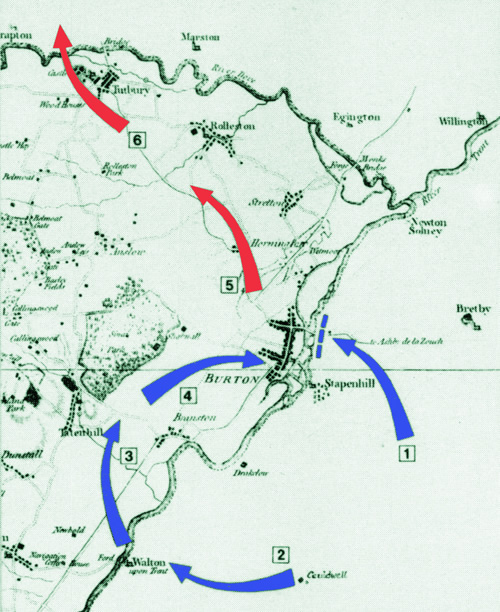

In retaliation, King Edward II (pictured) decided that he would lead an attack against Tutbury Castle and assembled an army in London.

In retaliation, King Edward II (pictured) decided that he would lead an attack against Tutbury Castle and assembled an army in London.

In 1629, the county Justice of the Peace, who was appointed by means of a commisssion to ‘keep the peace’, appointed Constables. Constables in turn appointed common warders to apprehend rogues and vagabonds. The warders appear though, to have been over zealous and were asked later the same year to show greater respect to poor people. Beggars from outside the parish remained a problem in the 18th century and keeping them out of town was one of the duties of the crier in 1711.

In 1629, the county Justice of the Peace, who was appointed by means of a commisssion to ‘keep the peace’, appointed Constables. Constables in turn appointed common warders to apprehend rogues and vagabonds. The warders appear though, to have been over zealous and were asked later the same year to show greater respect to poor people. Beggars from outside the parish remained a problem in the 18th century and keeping them out of town was one of the duties of the crier in 1711.