Joe Fox

A collection of paintings from local artist, Joe Fox

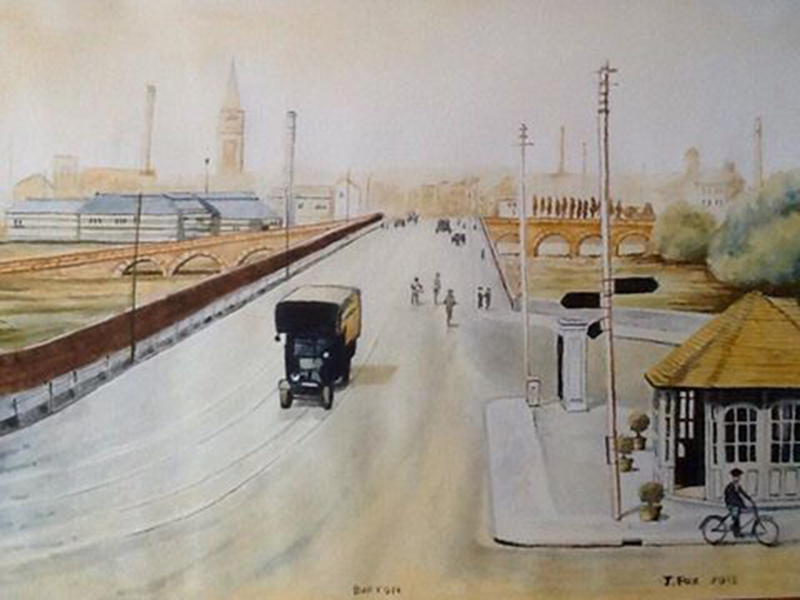

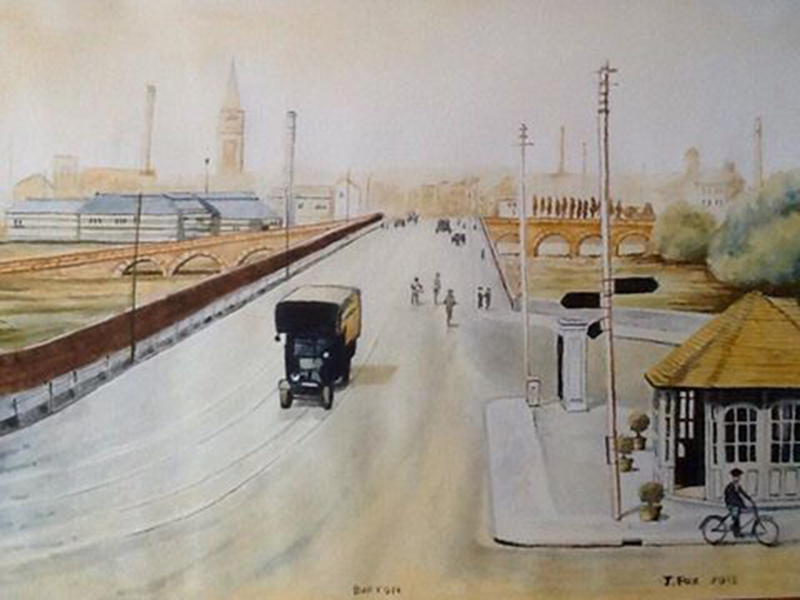

Trent Bridge (inspired by a photo on this website)

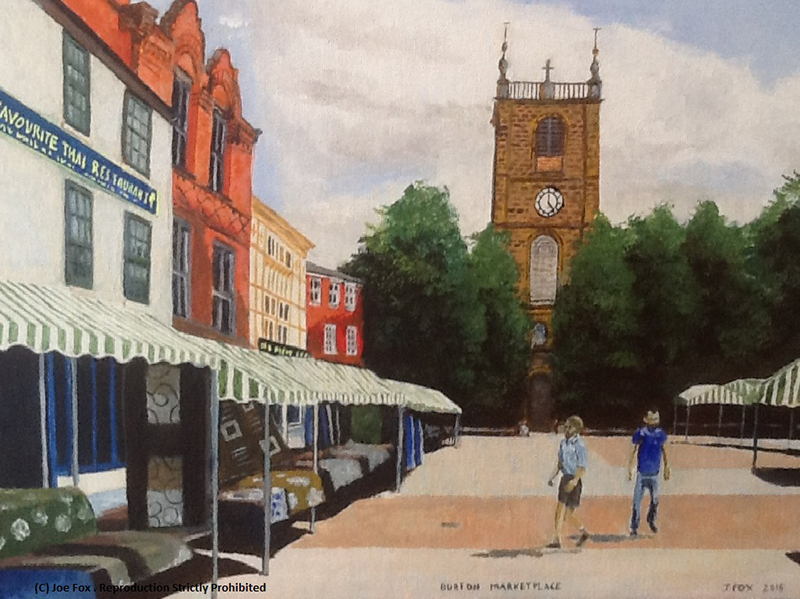

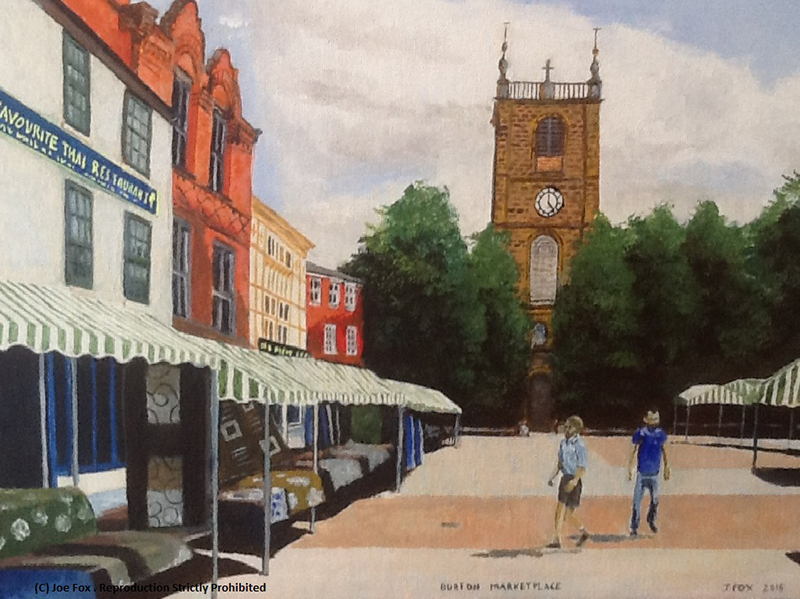

Burton Market Place

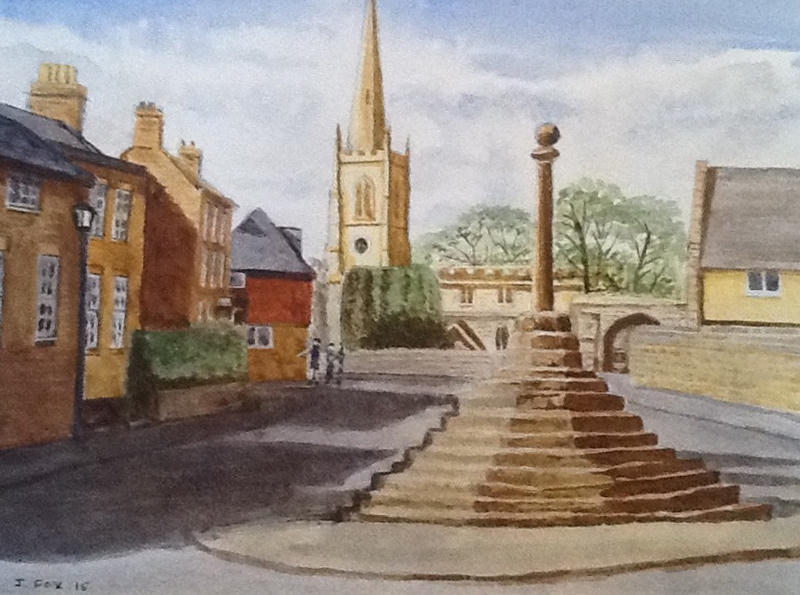

Repton Cross View 1

Repton Cross View 2

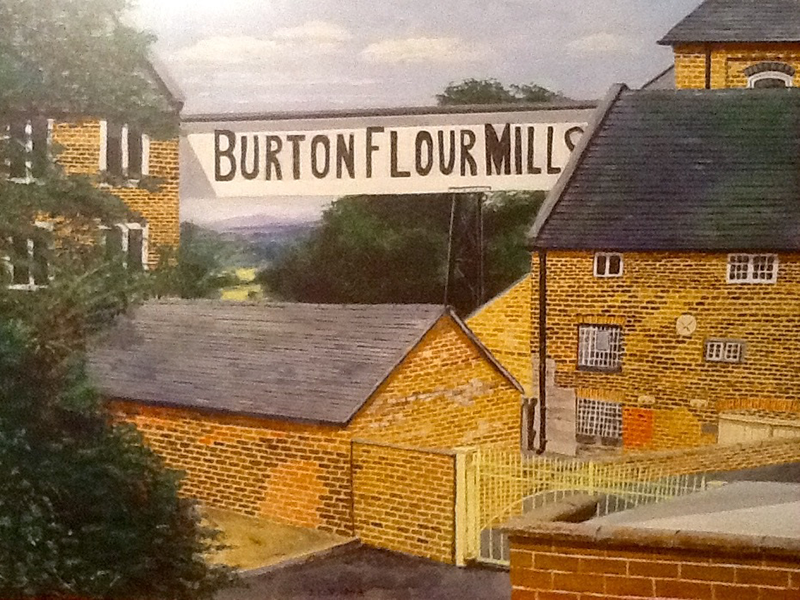

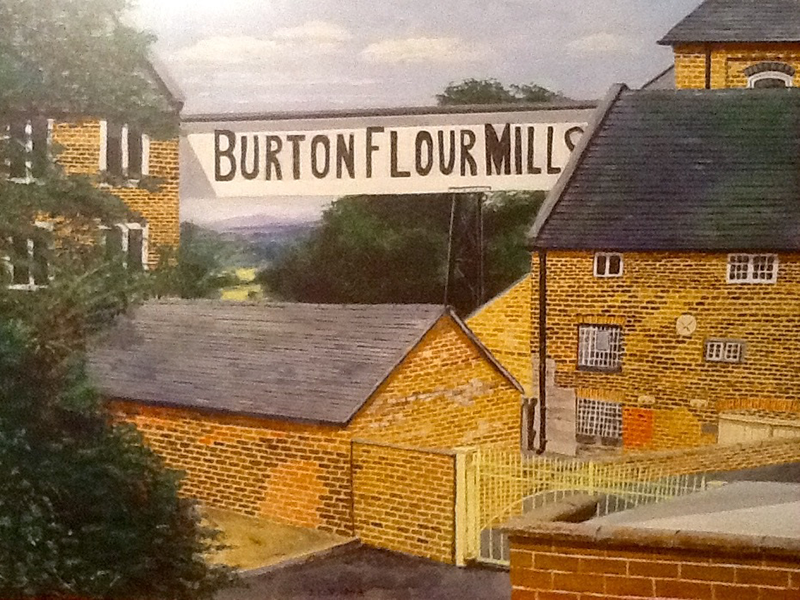

Burton Flour Mills

Repton Cottage

|

|

A collection of paintings from local artist, Joe Fox

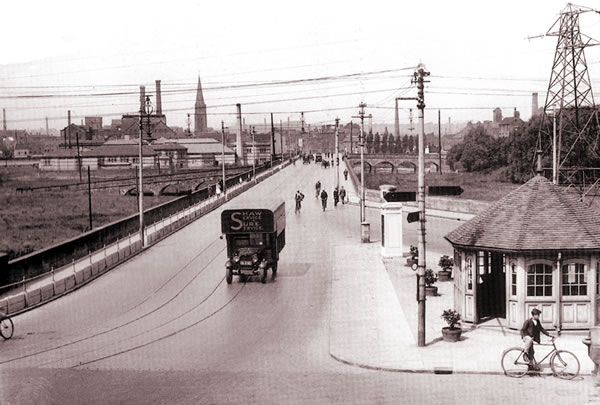

Trent Bridge (inspired by a photo on this website)

Burton Market Place

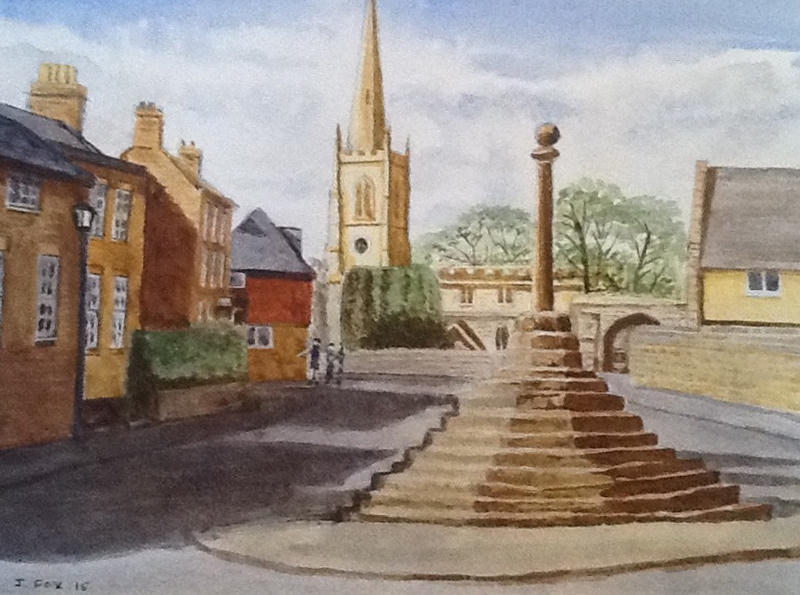

Repton Cross View 1

Repton Cross View 2

Burton Flour Mills

Repton Cottage

A collection of paintings from local artist, Cherie Bakewell

Burton Flour Mill

Ferry Bridge

Burton Abbey

Bretby Village

Rowing Clubs

Andressey Bridge

Repton Cross

Many images have been painstakingly restored before being featured. The primary aim has been to obtain the cleanest possible image completely faithful to the original photograph.

With a little effort, it is even possible to convert a black and white photo into a colour one such as this example:

This section contains sets of images of Burton by local artists.

If you have a similar collection and would like to have them featured, please feel free to submit them.

Below is a short history of Branston Pickle, one of a number of famous brands to emerge from Burton upon Trent, with thanks to John Sarson.

Crosse & Blackwell was a fast growing food Company around this time with take overs and mergers including Keillers marmalade and Thomas & Edward Pinks jam & pickle business. Their Soho Square factory was deemed too small and they were also advised they would also have to make way for redevelopment in the area.

In April 1921 Crosse & Blackwell finalised the purchase of the 150 acre site from the Disposals Board of HM Government after a dispute about the removal of machinery. They pledged to turn it into the largest & best equipped food preserving plant in the British Empire.

Alongside the purchase of the Factory they also purchased Branston Lodge in Burton Road (demolished in the 1960’s to make way for Lonsdale Road) as a residence for single female workers. They also built 26 houses along Burton Road for the use of the Factory foremen which were designed by Sir Aston Webb and known as the ‘Wayside’ houses.

In 1921 Crosse & Blackwell closed their Soho Square Factory in London and moved production of preserves & pickles to their new Branston Factory. Those staff who had completed seven years service received one weeks redundancy pay per year served at a total cost to Crosse & Blackwell of £22,500.

In 1922 Branston Pickle was invented / developed at Branston Lodge. Mrs Graham & her two daughters, Miss Evelyn & Miss Ermentrude are the attributed inventors although this is not verified. It is probable that a sauce predates the pickle. The recipe remains the same one as used today.

Branston pickle went into production in the same year at the Branston Factory which employed c600 people two thirds of which were female.

Most of the ingredients were sourced from Covent Garden in London with half the production returning to London for export. Crosse & Blackwell produced a price list in three languages, English, French & Spanish.

Crosse & Blackwell were coming under financial pressure due to recent growth & spending and considered the Branston operation as being too expensive. During 1924 it moved production back to London to the Thomas & Edwards Pinks factory in Crimscott Street, Bermondsey and completely ceased production at Branston in January 1925 selling the site in 1927 to Martin Coles Harman (at the time the owner of Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel) for use as the Branston Artificial Silk Company. This caused a substantial loss of work for local people and many people boycotted Crosse & Blackwell products.

The ‘Branston’ trade mark was registered by Crosse &Blackwell in 1929

During 1933/34 production of Branston Pickle was moved to the Keillers marmalade factory in Tay Wharf, Silvertown, London and the old Bermondsey factory was demolished in 1935 Crosse & Blackwell was bought by Nestle in 1960.

An early advert informs: “The Ten O’Clock Test makes Branston the most popular sweet pickle in the world. You’ll probably be the most popular girl when you serve Cross & Blackwell Branston Pickle. So start spoiling the man in your life by giving him Branston… with cheese, cold meat, salads, and savouries. Look for the jar on your grocer’s shelf”. Give the age of the advert, it is unlikely that the modern day phallic connotation is deliberate!

A television advert was launched in 1972 to promote the product with the lyric ‘Bring out the Branston’. Although the advert finished in 1985 it still remains a familiar lyric to many people to this day.

Production of the pickle was transferred to the Crosse & Blackwell factory in Peterhead, Aberdeen in 1992 where items such as tinned baked beans and tinned sausages were being produced (170 employees). The factory closed in 1998 in an efficiency drive by Nestle. Production of Branston pickle was then transferred to the Rowntree Mackintosh / Gales Honey factory at Hadfield, Glossop, Derbyshire.

Branston Pickle was voted as one of the top 50 UK brands of the 20th century in 1999. In 2002 Walkers launched a Cheese & Branston Pickle flavoured crisps.

In 2002 it was time for a change of ownership again with certain Crosse &Blackwell brands, including the Crosse &Blackwell Branston brand, being purchased from Nestle by Hicks Muse, Tate & Furst (a USA private equity enterprise) to become a part of their UK based Premier Foods Company. J M Smucker & Co took over elements of the Crosse &Blackwell brand in the USA.

Premier Foods transferred the production to a factory in Mildenhall Road, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk in 2004 (365 employees). A factory fire at the site in October of the same year temporarily halved the availability of Branston Pickle causing panic buying across the country.

From 2005 the ‘Branston’ brand was extended to include baked beans, beetroot, pickled onions, relishes, mayonnaise, etc. Branston Pickle alone sold over 28 million jars in 2006 and was available in over 50 countries around the world and can claim to be a world famous product.

The ownership again changed in 2012 with the ‘Branston’ brand being sold by Premier Foods to Japanese food firm Mizkan, based in Burntwood, Staffs, for £92.5m including the Bury St Edmunds Factory. Premier Foods had rapidly expanded, mostly through takeovers, to become the UK’s largest food producer and had found itself struggling under a large amount of debt and wanted to focus its recovery on other key brands.

The site today still allows many glimpses into the past; the main entrance is little changed.

The characteristic border wall which still dominates much of Branston Road marks the boundary but a peep over the wall reminds of grander years.

The distinctive row of houses at the end of the main Branston Depot site also belonged to the factory and housed some of its most important staff.

Below is a short history of what most Burtonians simply know as Branston Depot. With thanks to John Sarson.

During World War One, as a part of the National Factories Scheme, HM Government commissioned the Enfield Small Arms Factory to design a National Machine Gun Factory to be built on 150 acres of open fields along the North side of Burton Road in Branston. Amongst the reasons Branston was chosen was that it was out of reach of enemy aircraft. The site was being used at the time by the Burton Golf Club who moved to Bretby and also as Woodwards Farm.

The Factory was built by local builder Thomas Lowe & Sons and was started in 1917 but not fully finished before the First World War ended in November 1918. Gun making machinery, much from the USA, was installed on the site but it was never used to produce machine guns although it was used to recondition about 1000 of them. The distinctive long brick wall fronting onto Burton Road was built by German prisoners of war who were housed in local brewery maltings buildings.

A large three storey office block was built near to the site entrance which featured a four faced clock on the top of it. The clock required winding regularly and although it is still in working order today the practice has fell into dis-use. Only one of the four large warehouses which were originally planned was constructed and had north facing roof windows to give an even light throughout the day.

The site had an internal railway system connected to the nearby Birmingham and Derby Junction railway. It also had a fire station situated on the left side of the main entrance which was demolished in 1995/6. The site also had a joinery, c6 air raid shelters, a pump house, a vehicle workshop and many other buildings totalling 118 in all. There was a rifle range running parallel to the Birmingham and Derby Junction railway line at the rear of the site which had a large brick wall and embankment at the target end of it (the range was closed in 1965).

Questions were asked in Parliament on the 3rd May 1920 about the future of the site and it was advised that a tender to purchase it for £550,000 had been made by M Girardot to turn it into a car factory but this offer had been declined. The Government offered to sell it to him for £600,000 but he had also declined. Subsequently, a bidding process went to sealed bids with Crosse & Blackwell making an offer of £612,856 and M Girardot offering £576,000. The bids were opened on the 29th April 1920 with a sale being agreed to Crosse & Blackwell.

Crosse & Blackwell finalised the purchase from the Disposals Board of HM Government in April 1921 after a dispute about the removal of machinery pledging to turn the Factory into the largest & best equipped food preserving plant in the British Empire. They called it their Chief Factory on the labels of their products.

Alongside the purchase of the Factory Crosse & Blackwell also purchased Branston Lodge next to the Leicester line railway bridge in Burton Road as a residence for their single female workers (demolished in the 1960’s). They also built 26 houses along Burton Road for the use of the Factory foremen which were designed by Sir Aston Webb and known as the ‘Wayside’ Houses.

Crosse & Blackwell closed their Factory at Soho Square in London and commenced production of pickles at Branston in 1921 employing c600 people of which two thirds were women. Mrs Caroline Graham & her two daughters, Miss Evelyn & Miss Ermentrude are attributed with producing the Branston Pickle recipe at Branston Lodge and production of it started at the Factory in 1922. Most of the fruit & vegetable ingredients were sourced from Covent Garden in London and over half the production returned to London, much being for export.

During 1924 Crosse & Blackwell became under financial pressures and considered the Branston Factory was too costly and decided to move production back to London and completely finished production at Branston in January 1925. This precipitated a large loss of employment and many local people boycotted Crosse & Blackwell products for a considerable time.

In 1927, Mr Martin Coles Harman, a London financier, the owner of Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel at the time, formed the Branston Artificial Silk Company to produce Rayon. He initially employed a small staff with many being recruited from Courtaulds, some of whom who were housed in the Wayside Houses.

In 1927/8 a large chimney was built at a cost of £17,500 to carry away the unpleasant fumes from the Viscose manufacturing process which used Carbon Disulphide. The chimney was 360 feet high and had a 45 foot diameter at the base and 21 feet 9 inches diameter at the top and had a two foot sway. It was believed to be the second tallest chimney in the country at the time and considered to be a local wonder. It was built by Thomas Richardson and after construction had started it was found necessary to strengthen the foundations which lay on silver sand with 49 concrete piles. The chimney was built of perforated bricks which were twice the size of a normal house brick.

The Branston Artificial Silk Company started production in a blaze of publicity and expected to employ upto 4000 people but, in fact, it never exceeded 500. Amongst other things, it was famous for its buzzer which signalled the start and end of the day and lunch break and could be heard over much of Burton and beyond.

On the 23rd July 1929 the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward V111 / Duke of Windsor) visited the Factory on a visit to Burton and was presented with an artificial silk scarf which had been woven at the Factory and embroidered with the Princes initials in purple & gold together with white ostrich feathers.

The Branston Artificial Silk Company had ceased production by the end of 1930 and the Factory closed down. The administrators arranged some short term leases until July 1937 when the War Office (Ministry Of Defence, MOD) took over the site to supply mostly clothing and some small equipment to the Army. The distinctive chimney was demolished in 1937 as it was considered to be a hazard to aircraft and a landmark for any possible future enemy action. The remaining three large warehouses which were originally planned were built making four altogether with a total area of almost one million square feet all of which were heated and had fire sprinkler systems. Some other smaller buildings were also built at his time.

Six luxury houses, including tennis courts, were built for the use of senior Officers in Hill Road adjacent to the buildings at the southern side of the site. These houses were demolished in the early 1990’s as part of the Regents Park development. 12 semi-detached houses were built in Lonsdale Road and 22 were built in Mellor Road for lesser ranks all of which were sold to the local ESDC Council in 1977 and remain today. The 22 Mellor Road houses were purchased for £177,000. The Mellor Road and Hill Road houses were accessed through the main site entrance. The houses in Lonsdale Road were accessed through another secure gate near to the Leicester railway line bridge.

The roads within the site were named after senior military officers, Wilcock Road, Wall Road, Cleave Road, Gartan Road, Dibble Road, Stephens Road, Mellor Road, Harvey Road, Jephson Road.

Some of the buildings were as follows :

No 2 — Large warehouse, (c255,000 square feet internal, 199,549 cubic metres) 700 vehicles, including the Green Goddesses (258,925 square feet when re-built in 2007- see below)

No 4 — Large Warehouse, (221,214 square feet internal). MAFF flour and sugar.

No 5 — Large Warehouse, (220,008 square feet internal). Commercial stocks for the Prison Service

No 6 — Large Warehouse, (257,750 square feet internal, 123,145 cubic metres) Prison Dept clothing/equipment/riot gear

No 16 — Radiac building. Dosimeters, Prison Officers uniforms.

No 25 — Home Office newly purchased vehicles, including awaiting bodies to be modified.

No 37 — G1 Division. Mechanical parts for Emergency Road Vehicles.

No 45 — Three storey Office block.

No 50 — Vehicle Workshop.

No 51 — Fire Station

No 52 — Gatehouse

No 70 — Electric Sub Station in Mellor Road

No 121 — Pump House

During the Second World War the site was used as an Ordnance Depot for the supply of clothing and other small equipment to the Army including, clothing material, overcoats, roped soled sandals, bootlaces, enough boots upto size 15 to kit out much of the Army, buttons, belts, caps, under clothes, de-mob suits, wellingtons, etc. Qualified tailors were employed to inspect uniforms received from production factories such as Davisons in Derby. Many sundry items such as air raid sirens, fire bells, hand stirrup pumps, whistles, regimental flags, etc, were also stocked.

The site employed more than 2000 people during this time who were searched at random as they left the site. This number reduced to around 1000 people after the war. The site also had a Personnel department and Medical Centre with its own doctor and nurses.

A large bus station was situated on the opposite side of Burton Road (between the entrance to Paget School and the entrance to the Toad Hole) which was distinguished by its surface of cinders and rows of metal pole barriers for the various bus routes. A second smaller bus station opened in the late 1950’s which was accessed at Jephson Road through a security gate.

There were a number of large forklift trucks on site and also c12 BEV’s which were small but powerful ride on traction vehicles used to pull trolleys around the site.

Two railway lines running North to South either side of warehouses 5 & 6 accessed all four of the large warehouses. British Railways shunted the wagons from the main line into sidings on the site from where two MOD engines undertook the site shunting. The site included an engine shed.

In 1962 the War Office (MOD) decided to close its Branston operation and move most of the work to the Central Ordnance Depot (COD) at Bicester, Oxfordshire and over the following two years all the stores were transferred and the remaining 100 people lost their jobs.

In 1964 Branston Depot was taken over by ‘Ordnance Disposal and Storage’, a civilian run complex of the War Office (MOD). The main function was the receipt and issue of ammunition components for Royal Ordnance factories and the storage and preservation of machine tools with nearly all of it being transported by train. It also handled used brass gun shells, metal and wooden ammunition boxes. The Depot remained open until April 1975 when the site was again closed.

The Supply & Transport branch of the Home Office took over the site on the 22nd September 1975. A change of policy from storing equipment at strategically widely scattered sites such as hangars on airfields to one of central storage led to 11 small storage sites around the Midlands being closed and the items being consolidated at Branston.

From September 1976 large warehouse No 6, with the use of some racking stored 17,500 pallets plus some bulk storage area, was used to supply 18 prisons, borstals and detention centres around the Midlands with most of their needs with the exception of foodstuffs. The store included a large stock of textile material used in the manufacture of clothing at prison workshops. Other items such as wardrobes, chest of drawers and bed headboards were also received from prison workshops. By April 1987 36 prisons around the Midlands were being supplied.

From March 1976 warehouse No 2 was used to store 405 Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) ‘Green Goddess’ fire engines. This number rose to 462 before they were moved to a third party contract warehouse at nearby Marchington in 1991. Also included were support vehicles such as pipe carriers, hose layers and Land Rovers. These Green Goddesses were used by the Military from November 1977 to January 1978 to provide fire cover around the UK during the Fire Service national strike. The Green Goddess’s have since been disposed of altogether by HM Government with many going to African countries. Some were believed to have been sold through the British Car Auctions at Measham.

From the late 1970’s until 1993 warehouse No 4 was used by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries & Food (MAFF) to store sugar and unfinished flour for use in any future national emergency. The stock was rotated regularly with upto six vehicles a day being handled. The sugar was managed by the British Sugar Company and the flour by Rank, Hovis, McDougall.

During the 1970s 80s, local Auctioneers Arnolds held disposal sales around four times a year in warehouse No 4 when members of the public and others could purchase items no longer required by the Home Office.

One of the smaller buildings was given over to store items on behalf of the Womens Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS). Other buildings were used to store all manner of things such as petrol cans, polling station booths, riot equipment, etc.

One of the smaller buildings (No 16) was designated as the Radiac building where dosimeters were received from suppliers, checked and stored. This equipment was used by the Police, Royal Observer Corps, Fire Service, County Emergency Planning Officers & other various Government Departments to test for low levels of radiation. A radiation plaque was put on the wall at the entrance to the site which caused much consternation amongst the local people who thought the site was being used for storing nuclear bombs.

Building No 16 was also used to receive, inspect and store Prison Officers uniforms for both men and women. Around 21,000 uniforms were stored to supply every prison in England and Wales as well as the Channel Islands, Gibraltar and two Prison Training Schools.

The staff working at the site considered the pay to be good for women but poor for men compared to jobs in the local breweries. Many of the staff were members of the Transport & General Union (T&G).

The site was used by The Royal Navy, The Royal Air Force, HM Customs & Excise to train dogs to seek out drugs and is still occasionally used as a dog training centre in 2013. The site was used as a training location for Prison Officers, Prison Service Industries & Farms Gardens staff. The Royal Navy Midlands recruiting team was based at the site. The Staffordshire Fire & Rescue Service used the site as a training base.

There was a large canteen with men being served on one side and women on the other. It has a large dancehall as a part of the Social Club run by the employees and there was also a bowling green. Dances were held regularly on a Saturday night from the early 1960’s and proved to be very popular until they died out in the 1970’s.

During the 1990’s most of the open land (84 acres) was sold for housing development with the c850 house ‘Regents Park’ estate being built on it. The link to the national railway system was removed. The remaining area on which most of the buildings stood was divided between an area for the Home Office use and an area for sub letting.

In 2002 many of the smaller brick buildings on the Home Office area (now the Ministry of Justice, MOJ) were demolished and a large 19,000 pallet modern high warehouse was constructed. It is primarily used as a supply facility for the prisons in England & Wales which supplys them with most of their needs with the exception of foodstuffs. Some items are also supplied to prisons in Northern Ireland. A smaller building (No16) is used as a records archive.

The vehicle workshop (No 50) is still used to service and modify/adapt vehicle bodies to MOJ specific needs. There are around 70 MOJ employees at the site in 2013.

In 2004 the four large warehouses were leased from HM Government by D.I.Y. chain B&Q for 5 years at a reputed cost of £13m for use as a distribution depot for kitchens & white goods (fridges / washing machines / cookers, etc) and employing over 400 people. Third party contractors including TNT, CEVA and Wincanton (from February 2013) operated the premises on behalf of B&Q. In February 2006 a major fire destroyed No 2 warehouse as well as inflicting damage to some nearby houses and causing millions of pounds worth of damage in total. The warehouse was the same warehouse which housed the Green Goddess fire engines and was later rebuilt. The lease to B&Q was renewed for another 5 years in 2009.

In 2012 plans were submitted by the current land owners, Bedell Estates Jersey, for the four large warehouses and certain other smaller buildings to be demolished and replaced with c450 houses, although this is unlikely to happen for a few years. The large office block (No 45), the canteen building and the pump house (No 121) are Grade 2 listed buildings and are not planned to be demolished.

The Ministry of Justice is a separate area from the possible housing development and will continue to use their part of the site.

Although much of the site remains intact after its numerous uses, it is the role as the Branston Pickle factory for which it is now most fondly remembered.

During World War One, HM Government commissioned a Factory, designed by the Enfield Armanent Company, to be built on open fields along Burton Road in Branston as the National Machine Gun Factory. The Factory was started to be built by local builder Thomas Lowe & Sons in 1915 but not fully finished before the First World War ended in 1918. Not a single machine gun was actually produced there.

The site remains intact today with many of the original buildings still standing. It has existed in a number of roles, most famously, for its production of Branston Pickle, named after the factory location.

Select page to view:

There are several places in and around Burton where you become aware of the presence of the canal, but rarely do we ever bother to piece them all together.

One great advantage of the canals is the always adjacent tow path which has the benefit of being continuous and completely flat making for easy pushbiking. I decided therefore, as an exercise (in both senses), to start at Willington and pedal right the way through to Barton to get a clearer picture of how all of the well known sections piece together and what lies between. If you are feeling less energetic of course, you could make the same journey via Google Earth!

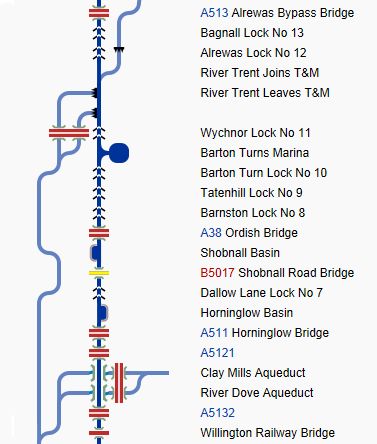

The above map shown here is a very short extract of a nationwide system of canals showing all bridges, aqueducts, basins, locks and its relationship with the Dove and Trent rivers.

The canal sits quietly under the modern, busy A38 close to the Clay Mills junction.

A couple of photos of what is perhaps Burton’s most distinctive canal bridge which can still be seen close to Shobnall Road.

A glance over the bridge is like peering into a bygone age.

A very short walk from familiar territory brings you to Dallow Lane Lock (Lock No 7); unchanged by time in the heart of Burton.

Finally, a posed photo taken in 1910 at Horninglow Wharf, the subjects unperturbed that the canal is frozen over.

The first recorded proposal to build a canal between the River Mersey and the River Trent was put forward in 1755, though no action was taken at that time.

The first recorded proposal to build a canal between the River Mersey and the River Trent was put forward in 1755, though no action was taken at that time.

Five years later, in 1760, Lord Gower, a local businessman, and brother-in-law of the Duke of Bridgewater drew up a plan for the Trent and Mersey Canal. If his plan had gone ahead, this would have been the first canal ever constructed in England. James Brindley (pictured), the engineer behind many of the canals in England, did his first canal work on the Trent and Mersey, though his first job in charge of construction was on the Bridgewater Canal.

Josiah Wedgwood was a strong supporter of the idea of a canal through Stoke-on-Trent to provide the smooth transportation from his potteries since road transport of the day resulted in many breakages. In 1761 he pledged his support although his major interest was simply in connecting the Stoke potteries to the river Mersey.

Much debate ensued regarding the possible canal routes. Coal merchants in Liverpool were among the strongest opposition feeling that they would be threatened by competing coal from Cheshire. The owners of the River Weaver Navigation were also not happy about the proposals, because the route would almost parallel that of the river. Yet another route was published, which much to the annoyance of Wedgwood, did not go anywhere near Stoke.

John Gilbert’s plan for the ‘Grand Trunk’ canal met opposition at the eastern end, where businesses in Burton on Trent objected to the canal passing parallel to the existing Trent navigation.

In 1764, Wedgwood managed to use his influence to convince Gilbert that the route should include the Potteries in his route. In 1766, Gilbert’s plan was authorised by an Act of Parliament. Later that year, a large ceremeny was held in the Potteries where Josiah Wedgwood cut the first sod of soil. James Brindley was appointed as engineer.

In 1771, still six years before the complete opening of the canal, Wedgwood built the factory village of Etruria on the outskirts of Stoke-on-Trent, close to the agreed canal route. Much of the canal had by now been built towards Preston Brook. The only major obstacle that still had to be solved was the hill at Kidsgrove, through which a tunnel was being dug. Up until 1777, wares from the new pottery had to be carried over the top of Kidsgrove Hill to the other side to the new canal.

The tunnel was known as the Harecastle Tunnel. Built by Brindley, it was 2880 yards long and barges had to be ‘legged’ through by men lying on their backs and pushing against the roof with their feet. This was a physically demanding and slow process and became somethcreated major delays, so leading civil engineer ing of a bottleneck. Thomas Telford later commissioned to provide a second parallel tunnel wide enough for a towpath. This tunnel was slightly longer at 2926 yards long and opened in 1827.

The tunnel was known as the Harecastle Tunnel. Built by Brindley, it was 2880 yards long and barges had to be ‘legged’ through by men lying on their backs and pushing against the roof with their feet. This was a physically demanding and slow process and became somethcreated major delays, so leading civil engineer ing of a bottleneck. Thomas Telford later commissioned to provide a second parallel tunnel wide enough for a towpath. This tunnel was slightly longer at 2926 yards long and opened in 1827.

On January 15, 1847 the Trent and Mersey Canal was acquired by the North Staffordshire Railway Company (NSR). This was done to stifle the opposition of the Canal Company to the creation of the Railway Company. In particular, the NSR had plans for a railway from Stoke-on-Trent to Liverpool, however, this line was abandoned due to opposition from other rail interests.

The Grand Trunk became part of a larger scheme known as the ‘Grand Cross’, still headed by Brindley. The idea was to link the four main rivers of England – Trent, Mersey, Severn and Thames, linking London to the major ports of Liverpool, Bristol and Hull.

The ‘Grand Trunk’ canal became known as the ‘Trent and Mersey’.

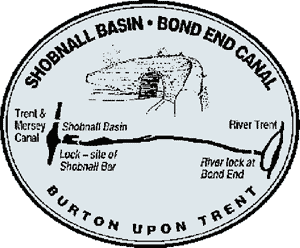

The Bond End Canal was once an important link between the Grand Trunk Canal and the river Trent.

Jannel Cruisers started business in 1973 in the tiny part that was left of Shobnall Basin. The Hines family reopened the basin and in 1980 created a dry dock on the line of the Bond End Canal. The original lock entrance walls can be seen at the entrance to the dry dock. The track of the Bond End Canal can be followed from Shobnall Marina, down Shobnall Road, over the railway bridge, along Evershed Way to St Peter’s Bridge at Bond End. However, Shobnall Marina is the only section still in water – hence anyone who uses Shobnall Marina’s dry dock can be said to have truly travelled to the ‘head of navigation’ of the Bond End Canal.

Below is a short history by Harry Hines:

Use of the river Trent, which runs through the town, had been tried since Roman times but the further inland, the smaller the boats that could be used. The winter flooding and shallows in the summer proved insurmountable, however cargo could be carried from the sea as far south as Wilden Ferry, where the river Derwent joins the river Trent and increases the quantity of water, then onwards by road. For example Staffordshire Waterways, by Staffordshire County Council Education Department, makes reference to (1765) “Great quantities of flint stones used by the potteries in Staffordshire brought to Hull and thence to Willington in Derbyshire to be forwarded by packhorse; and the fine ale made at Burton upon Trent and exported to Germany and several parts of the Baltic”. Hops, grain and malt were also carried to Burton via the river Trent.

Use of the river Trent, which runs through the town, had been tried since Roman times but the further inland, the smaller the boats that could be used. The winter flooding and shallows in the summer proved insurmountable, however cargo could be carried from the sea as far south as Wilden Ferry, where the river Derwent joins the river Trent and increases the quantity of water, then onwards by road. For example Staffordshire Waterways, by Staffordshire County Council Education Department, makes reference to (1765) “Great quantities of flint stones used by the potteries in Staffordshire brought to Hull and thence to Willington in Derbyshire to be forwarded by packhorse; and the fine ale made at Burton upon Trent and exported to Germany and several parts of the Baltic”. Hops, grain and malt were also carried to Burton via the river Trent.

In the early 1700s, improvements were made between Wilden Ferry and Burton to increase the depth of navigable water. Locks were built and the Burton Boat Company, under Henry Haine, prospered. Cheese, ale and pottery moved downstream and iron and timber upstream to and from the wharves and warehouses built on the river Trent at Bond End, just south of Burton Abbey. Bond End was so-called after the area outside the Abbey walls where the bondsmen and serfs, who served the Abbey, lived. Burton was now said to be the inland port the furthest from the sea.

Canals were gaining favour. A note found in the archives of the Staffordshire County Council says “It is another circumstance not unworthy of our notice in favour of canals, when compared with river navigation that is the conveyance on the former is more speedy and without interruptions and delays to which the latter are liable, opportunities of pilfering and other small goods stealing and adulterating wine and spirituous liquors are thereby to a great measure prevented.” With this thinking in mind, a canal to join the rivers Trent, Mersey and Weaver was proposed and surveyed in 1758. The Enabling Act was passed in 1766 for the canal to be constructed from Wilden Ferry to Preston Brook.

The Burton Boat Company, concerned at the loss of trade from their warehouses and wharves at Bond End, approached James Brindley, the engineer, to terminate the canal near Burton at Bond End. Brindley, considering the fluctuating water levels north of Burton to Wilden Ferry, refused the Burton Boat Company’s proposition.

By 29th September 1772 (Brindley died on 27th September), 48 miles of the Grand Trunk Canal (now known as the Trent & Mersey) from Wilden Ferry to Stone was navigable – the length past Burton-on-Trent being completed in 1770. Having been unsuccessful in persuading the promoters of the Grand Trunk Canal to modify the route, the Burton Boat Company, in 1769/70, built a 11/8 mile canal from their wharf at Bond End to Shobnall (the name deriving from Schobinhale, a family of Saxon knights) to connect the river Trent to the new Grand Trunk Canal. However, the canal company refused to allow a connection to the canal and a situation, known as the Shobnall Bar, ensued with boats each side of the bar having to be unloaded and reloaded. Whilst the reason of the canal company may have been to deprive the Burton Boat Company of trade and keep it on the canal, this was only partly successful as goods could pass both ways on the river using broad beam barges, whereas the canal was only broad to Horninglow and was narrow passing through Burton and onwards to Middlewich. The Burton Boat Company tried to gain trade by breaking through the bar overnight, but litigation followed and the bar was reinstated. Eventually a connection was allowed in 1794 and, as the Bond End Canal was at a lower level, a lock with a fall of 3ft 9in was constructed.

By 29th September 1772 (Brindley died on 27th September), 48 miles of the Grand Trunk Canal (now known as the Trent & Mersey) from Wilden Ferry to Stone was navigable – the length past Burton-on-Trent being completed in 1770. Having been unsuccessful in persuading the promoters of the Grand Trunk Canal to modify the route, the Burton Boat Company, in 1769/70, built a 11/8 mile canal from their wharf at Bond End to Shobnall (the name deriving from Schobinhale, a family of Saxon knights) to connect the river Trent to the new Grand Trunk Canal. However, the canal company refused to allow a connection to the canal and a situation, known as the Shobnall Bar, ensued with boats each side of the bar having to be unloaded and reloaded. Whilst the reason of the canal company may have been to deprive the Burton Boat Company of trade and keep it on the canal, this was only partly successful as goods could pass both ways on the river using broad beam barges, whereas the canal was only broad to Horninglow and was narrow passing through Burton and onwards to Middlewich. The Burton Boat Company tried to gain trade by breaking through the bar overnight, but litigation followed and the bar was reinstated. Eventually a connection was allowed in 1794 and, as the Bond End Canal was at a lower level, a lock with a fall of 3ft 9in was constructed.

In 1792/93 plans were published to build a canal from Burton, on the east side of the river to transport coal from the Derbyshire coal field. It was further proposed to join this to the Ashby Canal at Ashby Woulds and plans included an inclined plane near Newhall (predating the Foxton Inclined Plane by 7 years). There were also plans published around the same time for a canal to be built to the west of the Turnpike (now the A38) in competition to the Grand Trunk on the west side. This canal would have started where Bridge 88 now stands on the Coventry Canal, have 8 locks, cross the river Trent downstream of the present canal river crossing and join “Mr Peel’s Cut” at Bond End. “Mr Peel’s Cut” was made on the river Trent to supply power for the water wheels and water to the cotton mills opened by Robert Peel, a forebear of Sir Robert Peel MP – known as father of the police force. This cutting was also the termination of the Bond End Canal.

None of these plans came to fruition. It is interesting to note that these plans show the continued existence of the Shobnall Bar; indicating that the connection had not been made at that date.

In 1840 plans were published in another attempt to extend the Ashby Canal to join up with the Bond End Canal across the river Trent. About the same time there were plans to extend the Caldon Canal from its terminus at Uttoxeter to joint the Grand Trunk at Horninglow.

By 1843 the canal was used in a different way to solve a common problem of the times – sewage. The brick sewer built sometime after 1788 was liable to blockage and in 1843 the system was extended 2,159 yards to reach from the Trent Bridge to the Bond End Canal. A system was built connecting the sewer to the lock alongside the river so that every time the lock was used, water was forced through the sewer acting as a flushing agent. The quoted number of boats using the lock was 12 per day so allowing the sewer to be flushed 12 times a day.

The Birmingham & Derby Junction Railway brought their lines to Burton in 1839 with the first train arriving on 1st August. A spur line was built, from where Burton Station now stands, turning 90 degrees to terminate at the wharf alongside the canal. The main line crossed the canal on a moveable, probably swing, bridge. This was the site of an accident in 1846 when a railway porter, forgetting the imminent arrival of a train from Derby, turned the bridge to allow a boat through and the train engine ended up in the canal. Fortunately there were no fatalities but this led to the building of a fixed bridge that remained in existence until 1986.

The junction of the Bond End and Grand Trunk canals became a busy wharf and a public house, Mount Pleasant Inn, stood at the junction. There was never any road access to this establishment, known locally as “Bessie Bull’s”, nor was it equipped with beer pumps. Until its closure in 1961, beer was delivered from Marston’s Brewery across what is now the Trent & Mersey Canal and was drawn from the wood in the cellar. Thomas Bull, the landlord at the time of the pub’s closure, was the last of a family line to hold the pub’s licence that went back 102 years. The nickname of “Bessie Bull’s” dates to the last landlord’s grandmother, who took over the licence when she was widowed. It is thought that the pub may date to before the canal when it was understood to be called The Gateway to Sinai, a reference to nearby Sinai Park where a retreat was built for the Abbott and monks from Burton Abbey. The public house was demolished in 1962 and the Hines’ family home now stands on the site. The original tiled cellar was exposed during the modern bungalow’s building.

The Bond End Canal inevitably succumbed to the railways and by 1872 had become more or less disused. In 1874, one mile was infilled leaving the wharf at Shobnall as a transhipment point and sidings. Five railway lines were built around the basin and were in use until the 1950s. The North Staffs Railway Company laid its lines to Burton alongside the Trent & Mersey Canal, turning at right angles at Shobnall to enter Burton on the infilled bed of the Bond End Canal. A railway complex was built to serve the local breweries and the last train to use the line from Burton into Bass & Co’s maltings up the bed of the old canal to Shobnall was in 1974.