Girls High School – Waterloo Street

By the amalgamation of Finney’s Allsopp’s and Astle’s Charities, together with the Grammar School Endowments, provision was made for three Burton Endowed Schools, two for boys and one for girls. The latter, known as Allsopp’s Girls’ School, was opened in or about 1873, and was thus one of the earliest girls’ schools in the country. With Allsopp’s Boys’ School, it was housed in the Waterloo Street building now used by the School of Art and Crafts.

After the merging in 1884 of the two Boy’s Schools, the whole building was taken over by the girls’ establishment, henceforth to be known as the Girls’ High School.Miss Rutty was then Headmistress, with a salary of £75 per annum, half that of the Grammar School Headmaster, and a capitation fee of 15s. At the end of the century, there were about 120 pupils. In 1904 there was a move to establish ‘Secondary’ schools in Burton, but after meetings between the Governors of the Endowed Schools, Board of Education officials and the local authority, it was decided to make the Endowed Schools into the secondary schools for the town.

By 1905, various changes had taken place in the administration of the school. The governing body was now to consist of 13 members. Later, in 1909 it was laid down that at least two of these were to be women. A new scheme provided for a day and boarding school and also for a preparatory department taking both boys and girls.

The Girls’ High School at the turn of the century consisted of 120 girls, divided into six forms, with only one or two in the Vlth form. The Waterloo Street buildings, in two ranges connected by a long corridor, consisted of a ground floor only. The hall served also as a gymnasium, and in addition singing was taught here, much interrupted, after 1903, by the din of passing trams. At the end of the corridor, a partitioned space, to-day used for storage, formed Miss Rutty’s office, while a cottage at the side of the school contained a staff-room, a music room and the kitchen where Alice, the school maid, put out milk, 3s. 6d. per term, for break, and rang the bell for the end of lessons.

Corridor windows then looked out on a garden containing a tennis court and, beyond it, a croquet lawn. The tennis court was swept away in 1904 by extensions; extra rooms were built, opening off the corridor, with a Science room above, and another range, including a new office, was erected over the cloakroom; the latter rooms were connected by a balcony overlooking the gym. The staff moved to new, though still exiguous quarters within the school, and Miss Rutty’s office became Alice’s kitchen. Here girls congregated at break for milk and biscuits.

Although the girls had not the boys’ opportunity of learning Greek, the curriculum was broad for its day. Besides Religious Instruction, it included English, Latin, French, German, Mathematics, Geography, Ancient and Modern History, Drawing, Drill, Music, Natural Science, Domestic Economy and the laws of health, and Needlework. Singing was taught by Dr. Plant, organist at St. Paul’s Church, who also gave violin lessons. Plays were sometimes produced, and each form had a free afternoon. Past pupils speak of the friendly atmosphere which more than made up for dingy surroundings and inadequate gas-lighting.

There were few highly qualified staff, and Miss Rutty herself took French, German, and at one time, Mathematics. For the latter, it was rumoured, she was coached by the Headmaster of the Grammar School, thus keeping a lesson or two ahead of her own pupils. An old photograph shows her, a black toque on her red hair, small, erect, evidently a strong character, but affectionately known as Rusty Kate. A cultured woman, who, had received part of her education abroad, she was anxious to increase the prestige of her school and pupils took Cambridge Junior, Senior and Higher Local examinations, often more than once. As a result, examination nerves were almost unknown. These examinations were taken in the gym., usually with a male invigilator sometimes, the Bishop of Sodor and Man, brother of the then Vicar of Holy Trinity. In face of this dangerous situation, a group of local ladies took turns to come and sit during the papers. Cambridge Ladies were a feature of public examinations until the 1950’s.

Miss Rutty, proud of her school’s record in 1907 Cicely Hartley, top in the country in the Cambridge Junior examination, was given a gold watch by the Governors encouraged her pupils to continue their studies. Exhibitions were open to school leavers and a number of girls went on to Oxford, Cambridge and London. Prize-giving was a highlight of the year. At this function, for which the girls, in their best white frocks, assembled in the Town Hall, Miss Rutty’s brother, the Headmaster of Leatherhead School, always read the report. Miss Rutty although short-sighted would never wear her spectacles.

Much store was set on appearance and good behaviour. A mistress was always on duty to see that girls had their gloves on before leaving school. Anyone seen in town without gloves was severely reprimanded. One girl, seen walking arm-in-arm with a tram conductor, was expelled. The loss of order marks for work or conduct meant that one’s name was inscribed in the Black Book. Four such entries, and the culprit found herself at school on Saturday morning.

Girls of the Edwardian era contrary to the present popular image were athletic. Hockey practices took place on the Grange field, and by 1904 Miss Hurst was taking an XI to play rival teams. Tennis was played on the Grange courts, and cricket was a favourite pastime in summer. Swimming had been popular since the early days.

For gym, an optional extra until 1911, when it became compulsory, bloomers were worn under a long tunic rather like a coat. Miss Rutty liked her girls to be feminine, so the bloomers had, below the knee-band, a frill of their own material blue serge. Miss Linnell and Miss Hall later let that tradition die. This uniform was succeeded by a more modern tunic worn over a white blouse, with a navy and white tie. Long black stockings and black shoes completed the outfit. It was Miss Linnell who introduced the wearing of boaters, and also of the navy and white woollen cap with its flap which in cold weather was fastened under the chin.

Most girls walked to school; a few lucky ones, by private arrangement with Mr. Needham, were brought daily by cab to the top of the Station Bridge. The Jackson girls came in from Dunstall by pony-trap, with hot bricks to keep them warm in winter. Gertrude Wain trudged daily from her home between Bretby and Hartshorne, over the fields to Woodville, where she boarded a train for Burton. In winter, the hurricane lamp which had lighted her across the fields was hidden in a hedge, to be picked up on the return journey. Another girl, cycled from Newborough in all weathers. Anyone arriving drenched at school was sent to Alice, to dry out in front of a roaring fire.

Miss Rutty did take the occasional boarder, but this was never a regular thing. As the school served a wide area, ten or a dozen ‘plutocrats’ stayed to lunch, costing 8d. before the war. They were waited on by Miss Rutty’s maid, Sarah. Miss Rutty called each of her maids Sarah whether this was the girl’s real name or not. The others, numbering about 30, ate sandwiches in the luncheon room by the kitchen.

In 1913, Miss Linnell took over as headmistress. Within a year, in 1914, World War I broke out. As part of the war effort, girls knitted balacalavas, army socks and sea-boot stockings. They also engaging in varied fund raising for such as the Red Cross and organisations for sending food parcels to front line soldiers and prisoners of war. The school proudly gained a War Savings Certificate for raising over £1000.

After the (accidental) Zepplin raid on Burton in 1916, the school hours were changes as a precaution, ending the school day at 3:30pm instead of 4:15pm so that girls would be home before dusk.

The school was built to eventually accommodate 250 pupils, as was the case with most schools, this was soon exceeded. The rate of increase was as follows: 1900 – 120, 1905 – 156, 1910 – 213, 1915 – 289, 1920 -371 and by the end of the school year in 1921, there were 390 pupils.

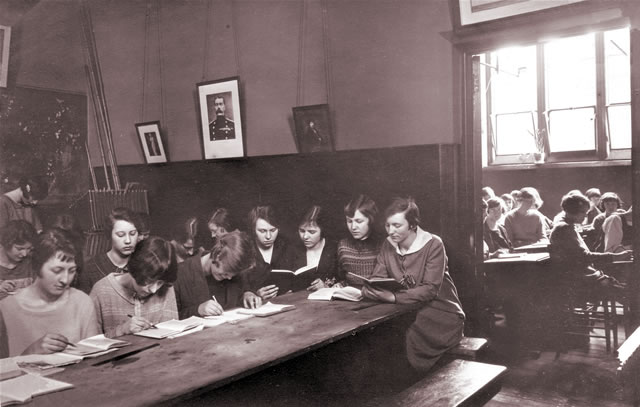

The corridor became used as a bicycle shed, library, staff room, waiting room, overflow dining room, study room and sick room – space was becoming very tight (although the above photograph does seem slightly contrived!). Extra accommodation had to be rented in St. Paul’s Institute and the sixth form used part of Miss Linnell’s own house.

Although a number of scholarships were available for less privileged children able to pass an entrance exam, most pupils at Waterloo Street were fee paying. Prior to 1882, fees were £2 for younger girls and £5 for higher students. In 1882, these were increased to £3 and £8 per annum.

By 1910, fees were £6 and £9 per annum but a number of additional fees were applied. Instrumental music gave the option of piano or violin with lower and higher fees of £1 1s and £2 2s per term. Swimming was now available but at the cost of 5s per season which was around half a year. Boarding fees were available for upto £50 a year.

Fees steadily increased to 1921 which imposed fees of £10 and £12 with similar proportion increases to extras but which now also included tennis for 3s or 5s per summer season. But 1922 saw the largest ever single increase which caused a few sharp intakes of breath when fees were increased to £15 15s for all students which could be demanded because the school was so over-subscribed.

The Woodlands site at Winshill had been acquired for a replacement school but post-war financial economies ment that it had to be shelved. It would be another seven difficult years before the delays came to an end and the school moved to Winshill in 1928.