Saint Paul’s Institute and Liberal Club

An extract from a map of Burton in 1865 below shows what was to become what we now know as the ‘Town Hall’ area. As can be seen it is quite isolated from the main body of the town with no road link between Station Street (recently renamed from Cat Street following the introduction of Burton’s first railway station) and Borough Road.

The area which was soon to see much development, was knows as Burton Moors. This started with the building of Saint Paul’s church by Michael Thomas Bass II a few years after this map was produced, opening in 1874.

The area which was soon to see much development, was knows as Burton Moors. This started with the building of Saint Paul’s church by Michael Thomas Bass II a few years after this map was produced, opening in 1874.

In 1878, Michael Thomas Bass II, around four years after the erection of Saint Paul’s Church, also decided to donate Saint Paul’s Institute to be built at the corner of two new streets established with the building of St Paul’s – Rangemore Street and Saint Paul’s Street East. While the Institute was under development, the brewing empire of Bass, Ratcliff and Gretton grew ever stronger and Mr Bass further extended the project and acquired adjacent land so that the scheme could be extended to include the Burton Liberal Club. At the time Mr Bass represented Derby as a Liberal MP.

The Institute was originally intended to be worked under one management but this arrangement was altered for the addition of a Liberal Club which involved considerable extensions, additions and alterations. The final Saint Paul’s Institute and Liberal Club building was erected at the sole cost of Michael Thomas Bass II. The total cost, including land acquisition, was just over £40,000.

Reginald Churchill of Burton was appointed and architectual plans were duly approved. The intention, according to Bass, was to “Better to provide for the scholastic, recreative, and intellectual requirements of the town“. The Institute was officially opened in January 1882, although the main hall had been finished earlier, celebrated with the first organ recital in 1881.

The below plans show the revised scope which, together with the image that follows, formed the centre spread in the 1883 Architect journal.

The original scope of the Institute can be seen below in blue. The large Liberal Club extension, included the distinctive clock tower, can be seen in red.

The now combined development was built in a decorated style in red brick with stone dressings.

In 1888 the benefactor’s son, Lord Burton, paid for the addition of a supper room with minstrels’ gallery, known as the Annexe, at the end of a corridor leading from the hall. This was also designed by Reginald Churchill.

The original proposal looks quite different to the present day image. I am currently trying to research how much of this is down to the original design being changed, and how much is down to later developments after the building was passed to Burton Borough to be re-used as the Town Hall.

The above impression based on the architectual drawing is the subject of a rare early postcard which was the basis of my colourized impression at the top of the page to reflects the architectual proposal of “red brick with stone dressing“.

An actual photograph that shows the original Institute with a number of lovely features missing from the current building, most notably the French style towers.

Some years later, after the building had been re-utilized as the Town Hall, the towers have been lowered, the large circular window added and a number of extensions, including a new two new entrances.

Saint Paul’s Institute

The Institute portion of the building, intended for the general use of the public, had its main entrance in Rangemore Street under an arched porticowas comprised of the public hall, three classrooms at the west end, three more classrooms at the east end, kitchen, larder, wash-up, stores, and cellars under, with cloak-rooms and back offices. It was also to provide a Sunday-school in connection with Saint Paul’s Church, the whole area of the hall and classrooms being occupied for this purpose.

The large west classroom was also used as a parish room, and the upper class-rooms for a children’s library and other purposes. A penny bank was also accommodated. Every convenience for public dinners was provided, apparatus for cooking and serving up the most recherche dinner for 350 to 400 guests being attached to the hall, in addition to which an ‘electro-plate’ was provided, as well as cutlery, linen, glass, earthenware, and kitchen utensils. The other sundries provided were portable tables convertible as high or low, screens, extra platform and proscenium for dramatic performances, and crimson felt for corridors and class-rooms, Sec, and a dancing cloth sufficiently large to cover the public hall when used for public balls, upon which occasions the club premises were used and the reading-room converted for the time into a supper-room. There were also rooms on an upper floor on either side of a large gallery.

The public main hall roof had traceried spandrels and brick decoration, and was panelled throughout in pitch pine, and carried on ornamental rolled iron ribs of Gothic outline and decorated. The interior walls were finished in coloured brickwork, in patterns relieved by stone pilasters, with carved caps carrying the ribs of the roof, the lower part having a dado 6 feet high of glazed red tiles between stone plinth and string-course.

A large traceried circular window was introduced at the west end, and the orchestra and a fine three-manual organ and case designed by the architect was installed in the east end; the original organ was worked by water-power. The hall also had a large stage.

Particular attention was paid to ventilation, which was provided by channels in the brickwork with openings through the window sills. Ventilation was provided by longitudinal cast-iron trusses and gratings in the roof connected with the fleche in the centre, and fresh air was admitted by ducts in each window-sill above the dado. Heating was effected by hot water-pipes in the floor and roof. The floors of all the rooms were laid with wood blocks on concrete. The walls throughout, except for the large main hall, were rendered in Portland cement and finished in Keene’s cement, and in the club portion of the building were covered with Lincrusta-Walton and richly decorated.

Since the building was formally opened, extensive additions have been made to the kitchen department. The kitchen itself has been doubled in size, and fitted up with a large range of gas-stoves, and an oven capable of heating 600 dinner plates at one time. A large, well-ventilated larder has been added as well as a wash-up place, store-room, and large cellar, into which the blowing apparatus of the organ has been removed, the wind being conveyed by an iron trunk through a subway under the floors, a distance of about 80 feet.

The original full-length mullioned windows were converted into arches formed by rectangular piers with heavy capitals when north and south aisles were added around 1900.

Liberal Club

The Liberal Club portion of the building is probably the part that most Burtonians think of because it included the Flemish style clock tower.

The main entrance to the Liberal Club was to be in Saint Paul’s Street (the Square did not yet exist), through a hallway which led to a reception room, decorated with Gothic arches. Originally, this included a refreshment bar which was an arcading of three pointed arches on polished granite shafts and carved caps, and was fitted up with buffet at back and every convenience. To the left was the games rooms with two billiard tables and chess tables. Also on the ground floor was the library which was furnished with about 3,000 volumes.

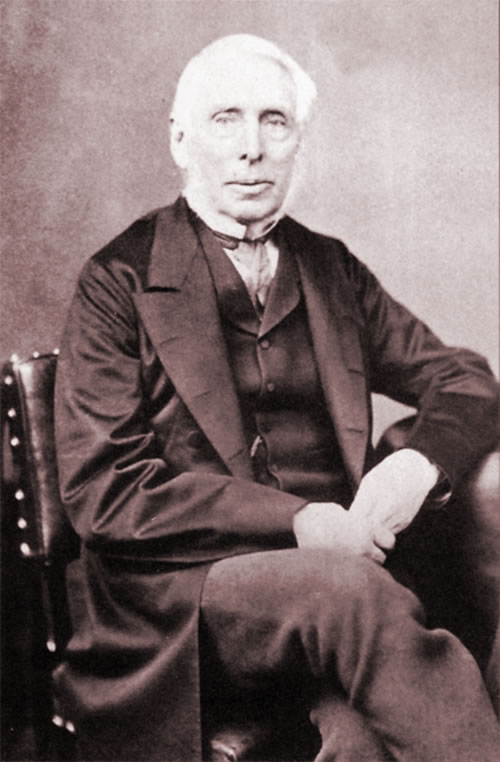

The staircase was of Wingerworth stone, with twisted iron balusters, and was most elaborately decorated. It receives light from a lantern roof panelled in pitch pine, and carried on stone shafts. The stairs provided access to the club’s reading room, above the billiard room, and library. On the landing at the top of the stairs, the original portrait of the benefactor, Michael Thomas Bass II, still stands proud.

The walls in the Liberal Club were generally of higher quality and covered with Lincrusta-Walton and richly decorated. The club premises were also furnished, and the floors lined with granite pattern linoleum throughout at the cost of Mr. Bass, including also 6 inch speculum telescope, two microscopes and ancilliary equipment by Mr. Browning, of London.

The tower contains a four-dial clock, striking Cambridge chimes, and hour-bell (in D) weighing 21 cwt was cast in 1879. The clock itself was manufactured by Mr. J. Smith, of Derby, and the bells by Messrs. Taylor & Son, of Loughborough.

A house for the club secretary was later built in the north-east corner of the complex, and a bowling green was laid out on the east side.

The general building contract was carried out by Messrs. Lowe & Sons, of Burton, assisted by Mr. de Ville as joiner, and Messrs. Pickering Bros., as plumbers. The fireproof floors were installed by Messrs. Dennett & Ingle. Mr. F. Stevenson carried out the whole of the decorations. The pattern-glazing was carried out by Mr. S. Evans. The entire of the filed floors and walls were supplied and fixed by Messrs. Minton, Hollins & Co. Mr. E. H. Cogswell acted as clerk of the works during a portion of the progress of the work. The whole undertaking was carried out under the personal supervision of the architect, Mr. Reginald Churchill, of Burton.

Replacement Saint Paul’s Institute

When the whole building was gifted to the Borough to act as a much needed Town Hall, start on a replacement building to serve Saint Paul’s, provided by Lord Burton, began in 1892 close to where the Saint Paul’s Court nursing home now stands, at the diagonally opposite corner of the church. As with the original Institute, it was designed by Reginald Churchill and, like the previous building, was of decorated style in red brick with stone dressings. The replacement building also included a hall, recreational rooms open to working men of all denominations,and Sunday school classrooms. It was opened in 1894 and administered by the vicar of Saint Paul’s church.

After several years of misuse, including being used to billet servicemen during the second world war, the building was sold in the 1970s and finally demolished in 1979. The coats-of-arms which can be seen on the Institute building were incorporated into the low retaining wall in front of Saint Paul’s Court and can still be seen today.

A replacement church hall was established inside Saint Paul’s church.

The man above is standing at the corner of Saint Paul’s church, diagonally opposite the original Institute, now part of the Town Hall.

Replacement Liberal Club

The second part of the building, displaced by the Town Hall, was the Liberal Club. A replacement was provided by Lord Burton in 1894, built in George Street. The new building was designed in French Renaissance style by Durward, Brown and Gordon of London and still retains the elaborate 16th century style plaster work.

Fortunately, unlike the Institute, this building still stands in very good condition and, seen above, will be recognised by most Burtonians standing on the corner in Guild Street. The club remained as the Liberal Club until 1944 when it closed and re-opened as George Street Club. It is currently used as a restaurant.