Ferry Bridge – The Ferry

IN THE BEGINNING

There is evidence to suggest that the early settlement across the river to the East of Burton that was to become Stapenhill arose because there was a convenience crossing point where the river was sufficiently shallow to be waded through. The original site is thought to be a little upstream from the eventual ferry site and this is thought to have some influence on the name of Ford Street still situated perpendicular to the river at the southern end of Ferry Street. Although wading across the river would have been no great obstruction to a strong adult, for the less physically able and for the transportation of loads across the river, or when the river was running high, it is thought that simple ‘boats’ were used to allow goods and people to be ‘Ferried’ across.

The crossing was to have additional significance because the river Trent used to be the defining line between the two counties, Staffordshire and Derbyshire meaning that passengers effectively travelled from one county to the other.

Although no ancient origins have been recorded, there is a record dating back to the reign of Edward I ‘Longshanks’ (1239-1307) of a man named William ‘The Shipman’, who died in 1286. There is the suggestion that he had the official role of Ferryman at this time which makes ferry boat activity around the site at least 700 years old.

The first firm documented evidence of a Ferryman comes much later, in the reign of Richard II (1367-1400). The site is now very close to the current site, most likely due to there being a more natural site from which to launch a more substancial boat. At this time, it was under the control of Burton Abbey.

Later still, there is documentary evidence in the form of a will dated 1496, by an Alice Bolde, who bequeathed two solid silver spoons towards the maintanance of the ferry boat which was still controlled by the still powerful Burton Abbey who were keen to oversee everything that passed between Burton and Stapenhill and Drakelow.

During the reign of Henry VIII (1491-1547), as part of the dissolution of Burton Abbey, all assets and income was seized by the King, which included any sources of income such as ferry rights. Along with everything else, these were gifted, together with almost the entire lands of Burton and surroundings extending as far as Cannock, to William Paget, a close advisor of Henry VIII and who was installed as first Clerk of the Council; a service for which he was knighted in 1543. Sir William was also made Baron of Beaudesert in 1549.

At this time, the Old Burton Bridge existed and had been built to ‘afford free passage for all across the Trent’ and so was free of toll. The first Baron of Beaudesert was compelled to provide a free means of passage further up the river between Burton and Stapenhill. A footbridge could not be funded so this was provided by Ferry boat. Before long, and strictly speaking, illegally, a penny toll was introduced by the Paget family to charge a fee to cross the river. Once established, a fee for crossing was continued when the management was eventually passed back to the Marquis of Anglesey, and continued right up until the ferry’s very last trip on April 3rd 1889.

Despite the toll charged for the ‘upkeep of the service’, in 1585, the wooden ferry was in such poor condition that William Paget was pressured into provided a new one.

A well known old ferry rhyme went as follows:

Across ye Trent to Stapenhill

And hack to Burton town,

A penny fee will carry me,

Tho’ well ’tis worth a crown.

THE FERRY MEN

In 1596, a small ferryman’s cottage was built on the Stapenhill side of the crossing. Operation was passed to an official ferryman in the form of a leasehold and he would reside in the cottage for its term. An annual payment was also payable to the local Lord. Above that, any fees taken by the ferryman were his from which he derived his family income.

Use of this cottage passed as part of the arrangement for each successive ferryman right through to the end of the nineteenth century. Each time the tenure changed hands, the outgoing ferryman had to ensure that the ferryboat was in perfect order or provide a new boat at the end of their lease period.

In 1771, the ferrykeeper’s cottage was replaced by the much more substancial Ferry House on the same site, which still stands today. It was also granted license to double as a public house. The cellar was cut deep into rock which, in the days before refrigeration, allowed ales to be kept in excellent condition for the time so it became a very popular venue and meeting house. A Mr Simmonds resided as both ferryman and publican who enjoyed a prosperous time up until 1825 when it met with a dramatic end. The story goes that a neighbouring baronet was returning home one night and wished to use of the ferry. In what was by then customary, he yelled “Boat, Boat!” which usually summoned the ferryman into service. On this occasion however, the cries went ignored because it was later than the published time for the last crossing. The baronet eventually had to resort to wading across the river fully clothed. When half way across the river, he became so enraged with the revelry and jeers coming from the inn that he fired upom it with a loaded gun he was carrying. His anger grew still further when he saw that some of the emerging patrons were actually amomg those he employed. Some of them were promptly dismissed and he made it his mission to ensure that the premises lost its license to serve alcohol and so its joint role as a public house came to an abrupt end. To add to the misfortune, some time later, a strong gale uprooted a large tree which crashed down onto the ferry house causing significant damage.

Mr Simmonds did not renew the lease which was taken up by Mr Lee with the property still showing signs of damage. In 1831, the post was sub-let to a Mr Preece who operated the ferry for four years until he retired in 1835. On Mr Preece’s retirement, Mr Francis Dalton, a Burton Hatter and his wife, Ann, obtained a lease on the house and ferry, still under management by the Paget family. Thus began the long tenure by the Dalton family which is most associated with the Stapenhill Ferry House which was to last for over fifty years. The building still showed signs of damange for the aforementioned accident when it was eventually sold to Mr Francis Dalton and it was he who finally took it upon himself to effect full repairs and ended up living there for the rest of his life until he died in 1871.

The census of 1841 records a Francis Dalton, Hatter, aged 25 and his wife Ann, aged 23 as the occupants of the Ferry House, with their children James, aged 2 years and Jane aged 5 months.

Despite its very long history, there are no reports of any fatality occurring from people using the ferry boat. There is, however, a record of a young man who drowned at the ferry in, or around 1839, after becoming entangled in some weeds half-way across the river whilst attempting to wade through the water after the ferry had closed for the day. After the Ferry House ceased trading as a public house the Punch Bowl became a favourite drinking place for many Burtonians, and the poor unfortunate had emerged from the hostelry at night and much the worse for drink. The ferryman had long finished his work for the day and so this foolhardy youth, likelyt aided with courage the beer had given him, attempted to cross the river without the safety of a boat and paid for his recklessness with his life.

A number of minor mishaps had occurred over the years with loaded ferryboats being upturned, resulting in the occupants being given a thorough soaking and weekly provisions from the shops and markets ending up on the river bed or being gobbled up by the ever present swans and ducks. On one occasion, the sinking of an overloaded boat resulted in the cancellation of a prize-fight. An argument at one of the Bond End pubs between two ‘bruisers’ resulted in a prize-fight being immediately arranged between the pair, and Drakelow Park was to be the scene of the affair. A great crowd then set off for the ferry and in their haste to arrive at the fight on time, a boatload of would-be spectators found themselves taking an unexpected swim after crowding onto the boat which very soon upturned, pitching everyone into the water. Not surprisingly, the fisticuffs contest was quickly forgotten!.

It was occasionally an eventful trip and not without its thrills and uncertainties. Apart from the craft sometimes overturning in mid-stream, as previously described; when fog descended the boatman might toil for a long time only to find at the end of it all that his boat and its passengers were still near the Burton bank. It was an eerie sound when the voice of a lonely traveller on its western bank echoed across the river for the, “Boat! Boat!” -the boat which sometimes never came.

JAMES DALTON – Last of the Ferrymen

James (Jimmy) Dalton, having been born at the Ferry House in 1839, had grown up and assisted his father there. When his father died in 1871, he was aged 32 and took over the operation of the Ferry.

The 1881 census records that 10 years after the death of Francis Dalton, the Ferry House was still occupied by the Dalton family with Ann, now 63 listed as ‘Proprietor of Ferry House’, and James Dalton (son) aged 42 as ‘Ferryman’ in her employment.

‘Jimmy Dalton’ became a well known local character and the subject of many local stories. Perhaps most famously, he was known for keeping a tame magpie which constantly ‘annoyed’ him by hiding his spoons and clay pipes. Around this time, a notorious criminal, Charles Peace was making national news and was hanged at 8:00am on February 25, 1879. To commemorate the occasion, Jimmy Dalton rigged up a miniature gallows and hung his magpie as the clock struck eight announcing that “Two rogues have gone together!”

Records for 1879 show that the ferry carried no fewer than 17,754 people per month. The journey across the river was sometimes a treacherous one. Periods after heavy rain made for a very fast flowing river with sometimes very muddy, slippy banks and a sometimes swollen brook still had to be negotiated once across the river. James introduced a number of improvements such as chain handrails across the brook and the firming of the boggy banks.

The roads and tracks leading down from Stapenhill to the ferry often caused concern to travellers, especially during wet periods and winter months. They had become little more than churned up muddy cart tracks often difficult to negotiate. With much hard labour, James Dalton strove to make the passage as safe as possible by patching the roadways with whatever suitable materials he could lay his hands on.

The pathway from the Burton side of the meadows led across the Fleet Green and Shipley Meadow (later known as Baldwin’s Meadow). There were a couple of planks were laid across the brook there, with just a post in the centre to assist users in balancing themselves whilst making their way over this crudely constructed bridge. Even so, many unwary travellers emerged cold and soaked to the skin after slipping into the water at this point in adverse conditions. On one occasion, an unfortunate man slipped off the bridge and was drowned.

Following this unfortunate incident, James Dalton was partly responsible for improving the bridge and adding a dis-used colliery chain to act as a handrail. The time was long overdue for the ferry to be replaced by a footbridge.

As demand for the Ferry grew, it became necessary to operate two boats at peak times to cope with the volume of passengers. James employed a number of different additional Ferrymen to assist in this role when required.

Following the eventual and inevitable closure of the Ferry when the bridge finally arrived in 1889, James Dalton gave up life on the river and went to work for his brother-in-law, John Webb, as a Tailor’s Porter in premises on Stapenhill Road with many ‘Tales of the Stapenhill Ferryman’ to share in the local taverns.

THE CASE FOR A FERRY BRIDGE

In 1800, the population of Burton was under 3,700; Burton Extra (Bond End) added just over 700. The population of Stanhill was less than 500. The population on both sides of the river grew steadily and by 1831, it reached over 4,300 for Burton, just over 900 for Burton Extra and Stapenhill had a population just short of 600.

As the breweries in Burton continued to expand and the workforce increased, usage of the ferry also began to increase proportionately. The population of both Burton and Stapenhill grew steadily with new houses springing up on both sides of the river with to accommodate them. By 1851, the population of Stapenhill had increased to 635; by 1861, this was over 1,100 and by 1871, there were almost 2000 inhabitants. With this rate of growth, two boats were now needed at peak times to handle the sheer volume of passengers across the river, although no figures ever seem to have been produced to give an accurate account.

The inconvenience of having to wait for the ferryman, often for lengthy periods, was voiced by an irate gentleman who wrote a letter of complaint to the Burton Weekly News in 1860:

“I should like to call attention to the shameful way people are kept waiting at the Stapenhill ferry. Now it may be very picturesque as represented in paintings, with fair, rustic maidens in bright, coloured petticoats and bare feet on a golden day in August, but when the waiting takes place on a stormy night, it is anything but picturesque, and very unpleasant. I have had to wait, when the attendant has been, I have no doubt, roasting his toes before a bright fire and until he has chosen to stir, I have had to stand catching a cold and losing my temper. Surely in this enlightened 19th century, ferries are behind the age.”

In the same year (1860), a complaint was made by a Mr T. Lowe, one of the Town Commissioners, concerning the bad state of the Fleetstone Bridge which, he observed, “was a complete disgrace to the town and ought to immediately be repaired”. For all the complaints about the Fleetstones bridge and the Ferry little was done towards making any improvements. The only improvement in fact, was the erection of a shelter on the Burton side of the river, due mainly to the efforts of a certain Councillor Redfern. Although always under consideration, it would be almost another 30 years before the building of the Ferry Bridge was to begin.

In October 1864, the council commissioned a census over a typical two week period to get some idea of the number of people using the ferry service. It revealed that 10,592 persons had used the Ferry service in that time. Similar records for 1879 show that no fewer than 17,754 crossings a month, sometimes significantly more, were using the Ferry. Given that service operated on a Sunday, that equates to almost 700 crossings a day making use of the ferry (of course, many of these were the same people making a return journey).

The population continued to increase relentlessly and it was estimated that over 4,700 inhabitants were now within the borough boundaries. This increase in the population naturally led to proportionate demands being made on the use of the ferry boat. Business was booming and the ferrymen were kept very busy. It was almost impossibly hectic on dates such as ‘Stapenhill Wakes Week’ and ‘Burton Statutes Fair’.

A new notice board which was erected at the boarding point advising passengers:

STAPENHILL FERRY

Open Sundays and weekdays for foot passengers.

Lady Day (March 25th) 5:30am till 10:00pm

Michaelmas to Lady Day 5:30am till 9:00pm

Fares l/2d each person.

Hand carriages (prams) l/2d each.

Weekly fares 3d, 4d or 6d. according to requirements.

Persons wishing to use the ferry before or after public hours

must make their own private arrangements with the ferry man.

An 1878 candidate for the Council wards of Stapenhill and Winshill stated in the local press: “James Dalton the ferryman has plied his honourable office long enough and must wish to retire and if James retired the ferry would not be worth preserving. The property on both sides of the river would be greatly enhanced by the addition of a new bridge”. The pledge to push for a bridge was a strong campaigning issue capturing the strong feelings of Burton and Stapenhill residents that the out-dated ferryboat conveyance was long overdue replacement with a suitable bridge.

Still without a bridge, according to a report which appeared in the Burton Observer in April 1889, no less than 185,000 persons were ferried across the river between May 7, 1888 and the beginning of April 1889, an increase of something like three thousand per week more than was the case less than ten years before.

THE RIVER TRENT

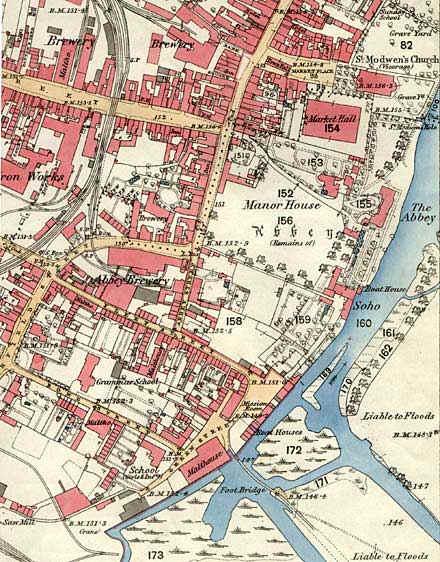

The river Trent diverges through Burton making a few islands. It is easy to think of this as being fairly static but it should be considered that the current course of the Trent through Burton, like much of the town, has changed dramatically since the times that the Ferry was in use.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the river downstream of the Ferry Bridge that flows past Stapenhill Gardens and round the bends between the Ox Hay and Stapenhill Hollow was NOT the main course of the river at this time! Rather, the river turned left just down from the present day Ferry Bridge into a mouth that is now only just visible as it forms the end of what is now known as the Silverway. It rejoined the main river some distance down at a point known as Alligator Point, froming an island known as Horse Holme which no longer exists other than the expanse of land that lies the otherside of the eastern woodland on the Ox Hay.

In the early 1800s, the Silverway itself was very wide and, in the summer, patronised by many bathers who swam in the river in the absence of the not yet build public baths. Even after the public baths were donated to the town by Richard and Robert Ratcliff in 1875, the Silverway was widely used and its use continued after the Ferry Bridge causeway was added.

At the Burton end of the causeway, the Fleetstones area contained a good flowing leg of the river with numerous boathouses and a rather precarious footbridge that had to be carefully negotiated. This flowed passed the Abbey and Saint Modwens chrurch but is now almost stagnant.