Stapenhill House and Gardens – General History

Stapenhill House was owned by the Spender family until 1820, when the owner, John Spender died, and it is thought that the house then was inherited by his children, including his daughter Sarah, whose husband, Joseph Clay, bought out the other heirs in 1824.

Stapenhill House was owned by the Spender family until 1820, when the owner, John Spender died, and it is thought that the house then was inherited by his children, including his daughter Sarah, whose husband, Joseph Clay, bought out the other heirs in 1824.

When Joseph Clay made his Will in January 1824, he stated that he had lately contracted to purchase “a messuage, dwelling house or tenement with all the outbuildings, yards, gardens, orchards and other appurtenances thereto belonging, situate and being in Stapenhill in the County of Derby, containing in the whole one acre, one rood and 26 perches … together with a seat in the north gallery of the parish church of Stapenhill” … and he left it all to his wife Sarah for her lifetime (she died at Stapenhill in 1831) and then equally to his surviving five children Two of the three sons had gone into the Church, the other son, Henry, became the owner of Stapenhill House, which he passed to his third son, Charles John, the elder two having become considerably wealthy, and having their own houses elsewhere.

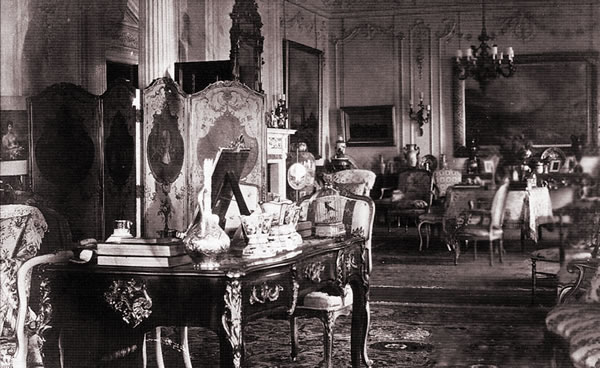

Joseph’s third son, Charles John Clay, eventually inherited Stapenhill House. The above photograph taken in 1878 shows Ernest Clay (rear), Arthur Clay (left), Gerard Clay (right), the elder three sons of Charles John, enjoying the house in its heyday.

This OS map extract from around the same time reminds that Stapenhill House knew very different times. Most obviously, the Ferry Bridge had not yet been built; a ferry boat was still in operation followed by a walk across the meadows to Burton. In wet weather, or if you could not afford the penny crossing, the only alternative was a walk to the Trent Bridge.

This OS map extract from around the same time reminds that Stapenhill House knew very different times. Most obviously, the Ferry Bridge had not yet been built; a ferry boat was still in operation followed by a walk across the meadows to Burton. In wet weather, or if you could not afford the penny crossing, the only alternative was a walk to the Trent Bridge.

Also very interesting to note, the main course of the river (and Staffordshire/Derbyshire county line) did NOT run alongside Stapenhill Gardens as it does now bu rather, turned left and cut across Andressey Island with a river bank close to the current footpath adjacent to the playing fields. The old course can just be seen on the North side of Saint Peter’s bridge up what is now known as the Silverway (bearly negotiable in a canoe).

Stapenhill House neighboured with Saint Peter’s Church and vicarage. The old vicarage garden gateway can still be seen as an isolated folly as you drive onto Saint Peter’s Bridge.

Stapenhill House neighboured with Saint Peter’s Church and vicarage. The old vicarage garden gateway can still be seen as an isolated folly as you drive onto Saint Peter’s Bridge.

The original Stapenhill House gardens ran to Jerrams Lane where they were surrounded by a high brick wall. This rare view from that direction reminds that the gardens once boasted among other things, extensive greenhousing, heated vinery, peach house and a large kitchen vegetable garden.

The original Stapenhill House gardens ran to Jerrams Lane where they were surrounded by a high brick wall. This rare view from that direction reminds that the gardens once boasted among other things, extensive greenhousing, heated vinery, peach house and a large kitchen vegetable garden.

Looking down the garden from Stapenhill House, it is slightly deceptive that the garden suddenly falls away down to another terrace next to the river.

Looking down the garden from Stapenhill House, it is slightly deceptive that the garden suddenly falls away down to another terrace next to the river.

The position of the main steps up from the river terrace (where Burton’s White Swan now stands) can still be clearly seen, although the actual steps have long since disappeared. Rather than the well known ornate gardens, the original Stapenhill House garden was simply a series of terraces with a hedge on the front of each.

The position of the main steps up from the river terrace (where Burton’s White Swan now stands) can still be clearly seen, although the actual steps have long since disappeared. Rather than the well known ornate gardens, the original Stapenhill House garden was simply a series of terraces with a hedge on the front of each.

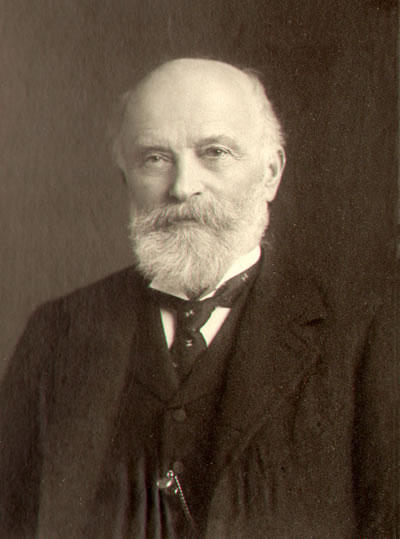

Shown above is Charles John Clay in 1908. Another Stapenhill House resident.

Shown above is Charles John Clay in 1908. Another Stapenhill House resident.

Gerard Clay, Charles John’s second son, of four, all of whom were born at Stapenhill House, and lived there until their marriage, after which Gerard and his bride lived at what is now Needwood Manor Hotel. Much more on Gerard Clay can be found on the website by descendent, Robin Clay.

Taken in 1915 from across the river, the above photo gives a marvellous view of Stapenhill House with the Ferry Bridge in the foreground providing a very good feel of how imposing the house would have been to people walking across the bridge.

The last residents of Stapenhill House were the Goodger family who were well established Burton solicitors. They purchased the land and estate from the Clay family in 1911. Mrs Mary Goodger J.P made her mark on Burton’s history by being installed as the towns first (and as far as I am aware, only) Lady Mayor for 1931/32. She died shortly afterwards.

The last residents of Stapenhill House were the Goodger family who were well established Burton solicitors. They purchased the land and estate from the Clay family in 1911. Mrs Mary Goodger J.P made her mark on Burton’s history by being installed as the towns first (and as far as I am aware, only) Lady Mayor for 1931/32. She died shortly afterwards.

In 1933 crippled by inheritance tax, the house was demolished and her son, Henry Goodger, passed the land to Burton Corporation in memory of his mother and Stapenhill Pleasure Gardens was established providing free public access.

The original re-structuring of the garden incorporated a windmill design, probably influenced by the fact that Burton at one time sported a windmill of its own close to the present day railway station.

Stapenhill Gardens remains a popular and distinctive feature of Burton in the guise of Stapenhill Gardens. A modern sign informs of its Stapenhill House heritage.

The gates still stand pround but it is as though the house in invisible allowing passers-by to look straight through to the rear gardens.

THIS PLEASURE GROUND WAS PRESENTED TO THE CORPORATION OF BURTON UPON TRENT

BY HENRY WILLIAM GOODGER IN MEMORY OF HIS MOTHER MARY GOODGER LATE OF

STAPENHILL HOUSE AND WAS OPENED FOR THE USE OF THE PUBLIC ON MAY 1ST 1933

Many of the original garden features are still in evidence, including the circle where my own children first learned to ride a bike without stabilizers!

And looking back to the steps that once led up to the main lawn. It is hard now to image a splendid house blocking the view to the road.

To the left on the above photo, you can just about make our the original Windmill design. Just to the right of it is the location of the original main steps that ascended to the main house. The White Swan stands on what was once a tennis court and close to where Saint Peter’s bridge now crosses was the boathouse.

The final view shows the Stapenhouse and Gardens site after its latest make-over.

Slightly confusingly, and rather cheekily, a significantly smaller house near the original site has recently adopted the name ‘Stapenhill House’ but there is no relationship between the two properties.

The Milligans

The Milligans Although Eva was the eldest, it was Blanche who was the best known and most dominant figure and in later years, was rarely seen out without her faithfull dog ‘Ben’; the two of them can be seen in the photograph on the right.

Although Eva was the eldest, it was Blanche who was the best known and most dominant figure and in later years, was rarely seen out without her faithfull dog ‘Ben’; the two of them can be seen in the photograph on the right.

In the 12th Century, defensive body armour used by knights had reached the level where the complete body was fully encase in armour, complete with full facial helmet. The downside of this is that it was not easily possible to identify anyone on the battlefield.

In the 12th Century, defensive body armour used by knights had reached the level where the complete body was fully encase in armour, complete with full facial helmet. The downside of this is that it was not easily possible to identify anyone on the battlefield.